In the tapestry of Kurdish history, few figures have interwoven as many vibrant threads as Nahida Salam. Educator, activist, poet, mother, cultural icon, and political trailblazer, Salam’s life story is one of extraordinary courage, intellectual depth, and relentless commitment to the Kurds and Kurdistan.

Born on December 7, 1921, in the Qazazakan neighborhood of Sulaymaniyah, Salam was the first child of the revered Kurdish patriotic poet Sheikh Salam Sheikh Ahmed Azabani and landowner Rawshan Saeed Kwekha Mustafa from Qaradagh. Her father’s early involvement in the government of the King of Kurdistan Mahmud Barzanji and the progressive mindset of the family led them to move to Sulaymaniyah, where Nahida Salam shattered social norms by becoming one of the few girls enrolled in the city’s only school. This came at a time when female education was still uncommon.

Her academic journey mirrored her father’s administrative postings across Halabja and Chamchamal in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate and eventually took her to Baghdad. In 1937, she enrolled in Iraq’s only teacher training institute for women – a groundbreaking step at the time – and graduated in 1941.

While in Baghdad, she often with her father visited Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji, then living under house arrest, who affectionately gave her the nickname “Karima”. At just 19 years old, she returned to Sulaymaniyah as a qualified educator, becoming both a primary school teacher and the headmistress of the city’s first kindergarten. This achievement was revolutionary in an era when most women were denied access to education. Her leadership not only opened doors for Kurdish girls, but also marked the beginning of a movement toward women’s empowerment and cultural preservation in Kurdish society.

In 1946, she married engineer Nouri Shaweis, a respected politician in his own right. The two met through their involvement in the Kurdish political parties and organizations of the time. Their life together took them across many Iraqi cities – Hillah, Shaqlawa, Erbil, Kirkuk, Karbala, Kut, Mosul, and Baghdad. Salam worked as a teacher while Shaweis served in the Ministry of Public Work and Housing. Their journey was often shaped by the political climate of the time, with Kurdish activists frequently punished by being transferred from their home cities in Kurdistan to southern cities in Iraq, even to other parts of Kurdistan. Salam ultimately retired as headmistress of Chiman School in Sulaymaniyah in 1970 after 29 years of service.

Political awakening and pioneering leadership

Nahida Salam started her political work in 1939 when she joined the Hiwa Party, beginning a lifelong commitment to Kurdish nationalism. Over the next ten years, she became active in several important Kurdish movements. In 1942, she was one of the editors of Truska, the journal of the Right Path Society, helping to share Kurdish ideas during a time of cultural awakening. Later, she joined the Kurdistan Revival Society in 1944 and the Kurdish Liberation Party in 1945, both focused on strengthening Kurdish identity and autonomy. In 1946, she became a member of the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), which was renamed the Kurdistan Democratic Party in 1951, and stayed loyal to its cause for the rest of her life. Her involvement in these movements not only supported Kurdish political goals, but also made her one of the first women to fight for national rights and gender equality.

Her reputation soared quickly. In 1960, she made history as the first woman elected to the KDP Central Committee during its fifth conference in Baghdad, reportedly at the personal recommendation of Mustafa Barzani. She was appointed as the party’s Public Relations Officer, but her role was far more than symbolic, as she helped shape policy, supported revolutionary strategies, and worked tirelessly to promote women’s participation in political life.

In 1952, Salam founded and led the Kurdistan Women’s Union, an organization that became – and remains – a major force in advocating for Kurdish women and promoting education. After the July 14 Revolution in 1958, she was elected to the Iraqi Peace Council membership and served as a member until the mid-1970s, aligning herself with progressive, anti-imperialist movements that challenged regional conservatism.

Building on her earlier achievements, she played a leading role in organizing the first conference of the Kurdistan Teachers’ Union, held in Shaqlawa in August 1959. During the conference, she led a group of teachers who strongly advocated for the inclusion of the name “Kurdistan” in the title of the newly established educational authority. Their efforts succeeded, resulting in the creation of the Directorate of Education in Kurdistan, a landmark decision that affirmed Kurdish identity within the educational system. This achievement reflected her unwavering commitment to cultural preservation and educational reform.

A life of exile and resistance

Nahida’s fight for freedom was never without sacrifice, coming at a heavy cost. When Shaweis joined the Eylul Revolution in 1961, she returned to Sulaymaniyah from Baghdad to be closer to the revolution. In the summer of 1963, as the Iraqi-Kurdish conflict intensified, her name appeared on a military watchlist issued by Colonel Sidki, the ruler of Sulaymaniyah. With her arrest imminent, she fled with her youngest son to the village of Dollan, where her mother owned land, leaving her other sons behind so they could continue their education. It was a choice no mother should ever have to make, yet she made it with courage and tears. For more than a year, exile was her reality.

In 1967, her defiance brought further punishment. The Iraqi government uprooted her from her home and sent her to Chibayish, a lonely village deep in the southern marshes. Refusing the deportation, she later went to Baghdad, but freedom was an illusion. Under the cold gaze of government surveillance, she lived in Hotel Khaldoon on Rasheed Street, with her every step watched, and every word weighed.

By 1974, the Ba’ath regime’s grip had tightened further. Salam was forcibly deported in the middle of the night from Baghdad with her two remaining sons, alongside other Kurdish families. Her home and belongings were seized and sold – for the third time since 1959. Homeless and stripped of everything, she crossed into Iran to reunite with her husband and her other sons . Yet even in exile, her spirit refused to break; her home in Naghda became a hub for Iranian Kurds, where stories of the Republic of Mahabad were retold with pride.

When the Eylul Revolution ended, she returned to Southern Kurdistan (Kurdistan Region of Iraq) with renewed resolve, throwing herself into political and social work and aiding underground KDP cells in Sulaymaniyah. Her home became a secret sanctuary for Peshmerga.

She could not, however, escape Saddam’s brutality. She would leave Sulaymaniyah and hide in Baghdad for months, blending into the crowded streets to avoid attention. Despite this, the Ba’ath continued to harass and threaten her. Every week, she was called in for questioning about herself and her children, living under constant fear and pressure. These were dark and difficult times that tested her courage and resilience.

The years brought no mercy. In 1996, during the Kurdish civil war, she faced yet another exile and the loss of her property. Forced to leave Sulaymaniyah, she settled for the last time in Pirmam, a suburb of Erbil. Through decades of hardship, displacement, and danger, Salam’s courage never faltered. Her life was a testament to her unwavering faith in Kurdish identity and freedom – a flame that no storm could extinguish.

Literary legacy and cultural impact

Salam was not only a force in politics, but she was also a formidable literary figure. Writing under pen names like “Kurdish Girl,” “N.S.,” and “Mother of Roj,” she contributed prolifically to Kurdish newspapers and magazines, particularly during the mid-20th century. Her voice – sometimes anonymous, always unmistakable – helped shape Kurdish intellectual and feminist discourse.

Her essays celebrated Kurdish identity, demanded unity, and advocated resistance against cultural erasure. She passionately called on Kurdish women to pursue education, take on leadership roles, and redefine their place in society. Through her writing, she built bridges between personal experience and national struggle, making literature her second front of activism.

Here is an excerpt from one of her short essays, translated from Kurdish to English, which were published in 1944 in the Galwex journal:

A Kurdish girl, one of my own people, stood there clothed in nothing but misery. She was pale, thin, and fragile – her body worn down to the bone. There was no place on her that hardship had not touched, no corner where exhaustion had not settled like an unwelcome guest. Only her eyes remained untouched, still shining within that frail, diminished frame. Her face looked unsettled, out of place. Her hands yellowed and trembling, bluish from the cold, lay weakly at her sides; the bones of her wrists jutted sharply beneath her skin.

With a frightened, broken voice, words escaping in fragments, she said: “I am human, just like you. I have the right to eat, to be clothed. I do not ask for a villa or a palace, only a piece of bread, something to wear, and a heart that can be happy. Why do you mock me?”

As a teacher in the first Kurdish kindergarten, she introduced national songs and integrated Kurdish identity into early childhood education. Her pioneering efforts were instrumental in laying the foundation for formal schooling for Kurdish children, particularly girls, at a time when educational opportunities were scarce. Through her dedication, she not only promoted cultural awareness, but also built a strong sense of Kurdayati – the feeling of Kurdishness – and pride in being Kurdish among her students. This early empowerment helped shape confident individuals who valued their heritage and identity.

She was a talented woman who succeeded in everything she tried. In 1968, she won first prize in the handicraft exhibition among the schools of Sulaymaniyah, showcasing her artistic skills in Kurdish dress and cultural artifacts. Earlier, in 1951, as a sports teacher and organizer, she helped the Ayubia Girls’ School win the cup for best school at the sports day in Erbil. Many people still remember that day. Even the Hawler journal, in its 19th issue, celebrated the victory and wrote about her, mentioning the patriotic songs her school sang during the event, something considered noble in Erbil at that time. She was known not only for her creativity and intelligence, but also for her strength and determination. These achievements reflected her ambition and resilience – qualities that shaped her life.

Despite her strength as a leader and her tireless dedication as a politician and to her family responsibilities, my mother never lost touch with her feminine essence. She carried the weight of responsibility with grace yet always celebrated beauty and elegance. Her love for fashion – both Western styles and traditional Kurdish attire –reflected her dual identity: modern and progressive yet deeply rooted in her heritage. Jewelry sparkled on her hands and neck, and vibrant Kurdish dresses adorned her figure, symbols of pride in her culture and her womanhood. She was proud of her femininity, her radiant face, and the charm that never faded, even in the most challenging times. Until the very end, she remained a woman of strength and beauty, a rare harmony of power and grace.

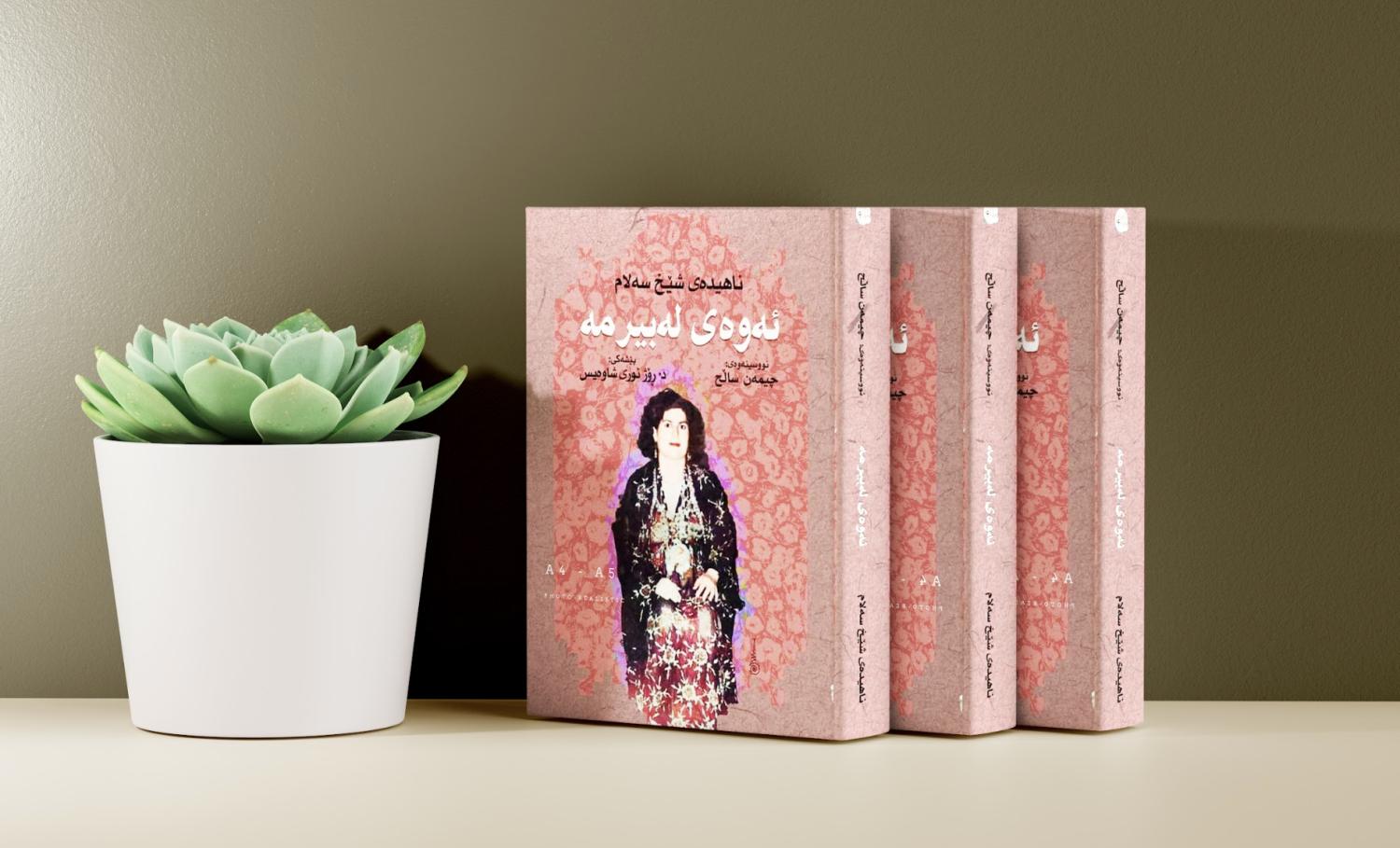

Her memoir Awai La Birma (What I Remember), first published in 1999 and republished in 2024, offers a vivid account of her personal experiences under political repression. Yet her life story goes far beyond individual hardship. It reflects her profound influence on shaping Kurdish culture, education, and political identity during a transformative era. Today, her memoir stands as an essential historical source, documenting not only her colorful life, but also the broader struggle of Kurdish women throughout the last century – a struggle for dignity, equality, and cultural survival.

Matriarchal legacy

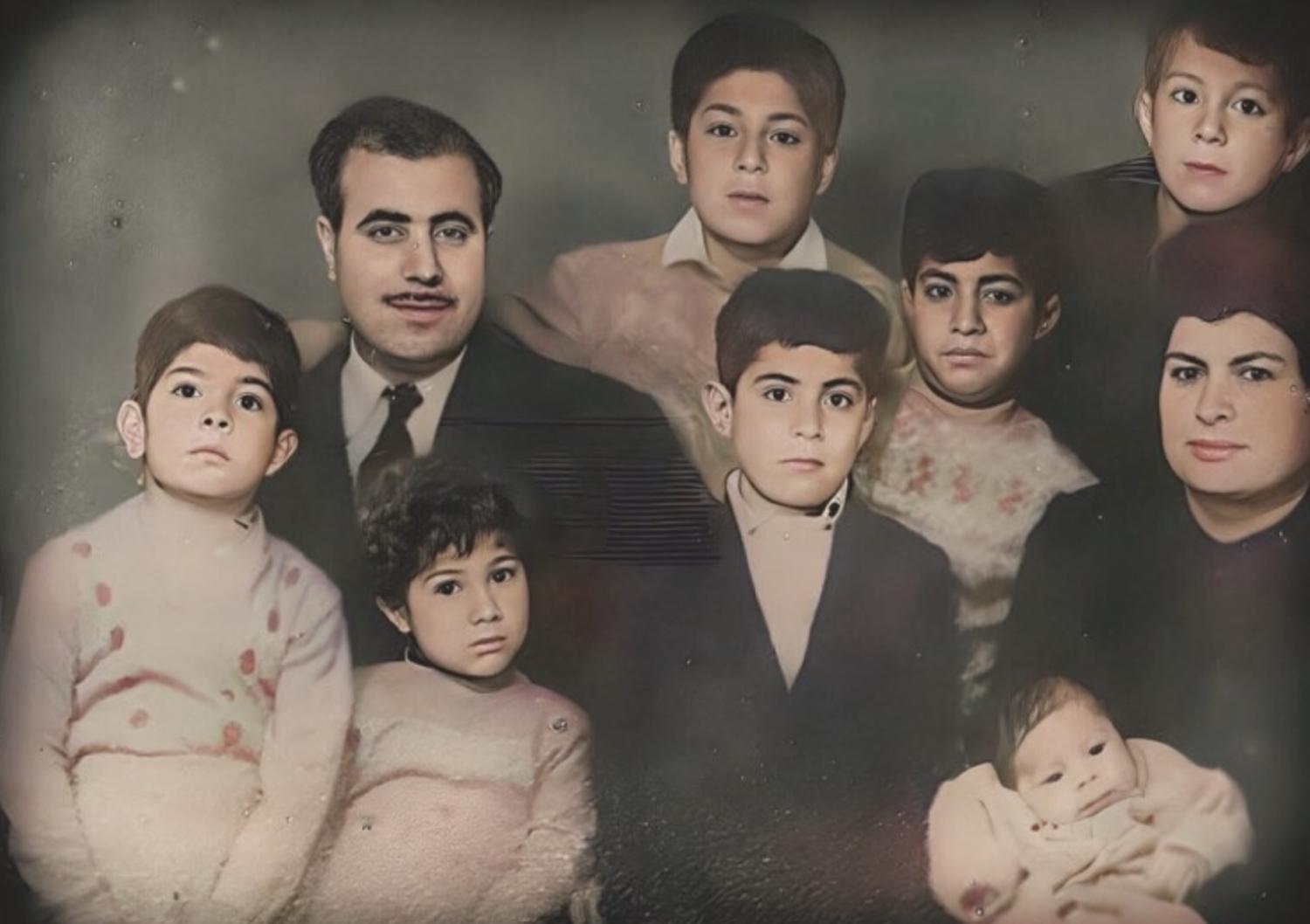

At home, Salam was the beating heart of a large and vibrant family. As the mother of eight sons and the grandmother to 18 grandchildren, she created a household deeply rooted in Kurdish values. Her love for Kurdistan was not merely taught, it was lived. Every meal, every story, every tradition carried the spirit of a homeland she cherished with unwavering devotion.

We grew up immersed in the rhythms of patriotism, service, and culture woven into our daily lives. She believed that identity was not something to be spoken of occasionally – it was something to be practiced, protected, and passed on. She nurtured not only bodies, but minds and souls, shaping generations who understood the meaning of sacrifice and pride.

For most of their marriage, my father was away with the Peshmerga, fighting for the freedom of the Kurdish people. In his absence, my mother carried the mantle of leadership with strength and grace. She was the anchor in the storm, guiding her family through years of uncertainty and hardship. Decisions that would have overwhelmed others became her daily responsibility, and she bore them with quiet courage.

Her motherhood was never separate from her strongly held nationalist beliefs – it was its foundation. Raising sons who would serve their nation was her mission. Her commitment to us came naturally, a reflection of her character, and was strengthened by her unwavering love for my father. That love was not passive; it was active, resilient, and blind to fear. It gave her the strength to lead, to endure, and to inspire her.

Salam’s life was a true example of the strength of Kurdish women, a reminder that behind every fighter on the front lines, there is often a woman at home holding everything together. Her courage came from her father’s encouragement, her mother’s background, her education, and, most importantly, the trust my father placed in her. Her legacy lives on through her children, grandchildren, students, colleagues, friends, her party and the many lives inspired by her example of dignity, devotion, and resilience

Commemoration and closing chapter

Nahida Salam passed away on November 28, 2006, in Erbil. She was laid to rest on Seywan Hill in Sulaymaniyah, alongside her beloved father, as per her request. Her passing marked the end of an era, but her legacy continues to inspire.

In tribute to her heroism and leadership, she was memorialized among 120 Kurdish women whose statues now stand in Erbil’s Downtown Market. These sculptures are symbols of resilience and remembrance: Salam’s reminds passersby of a life lived in service to justice, education, and Kurdish pride.

Her story also reminds us that true leadership doesn’t seek comfort – it demands courage. And when history called, Nahida Salam answered.

Dean of the School of Medicine, University of Kurdistan Hawler.