On November 27, two bomb-laden drones struck the Khor Mor gas field, disrupting production at the Kurdistan Region’s most significant energy asset. The consequences extended beyond the industrial site. As Khor Mor is central to regional power generation, the attack triggered a near-total power outage lasting several days, with severe consequences for daily life, commerce, and public services.

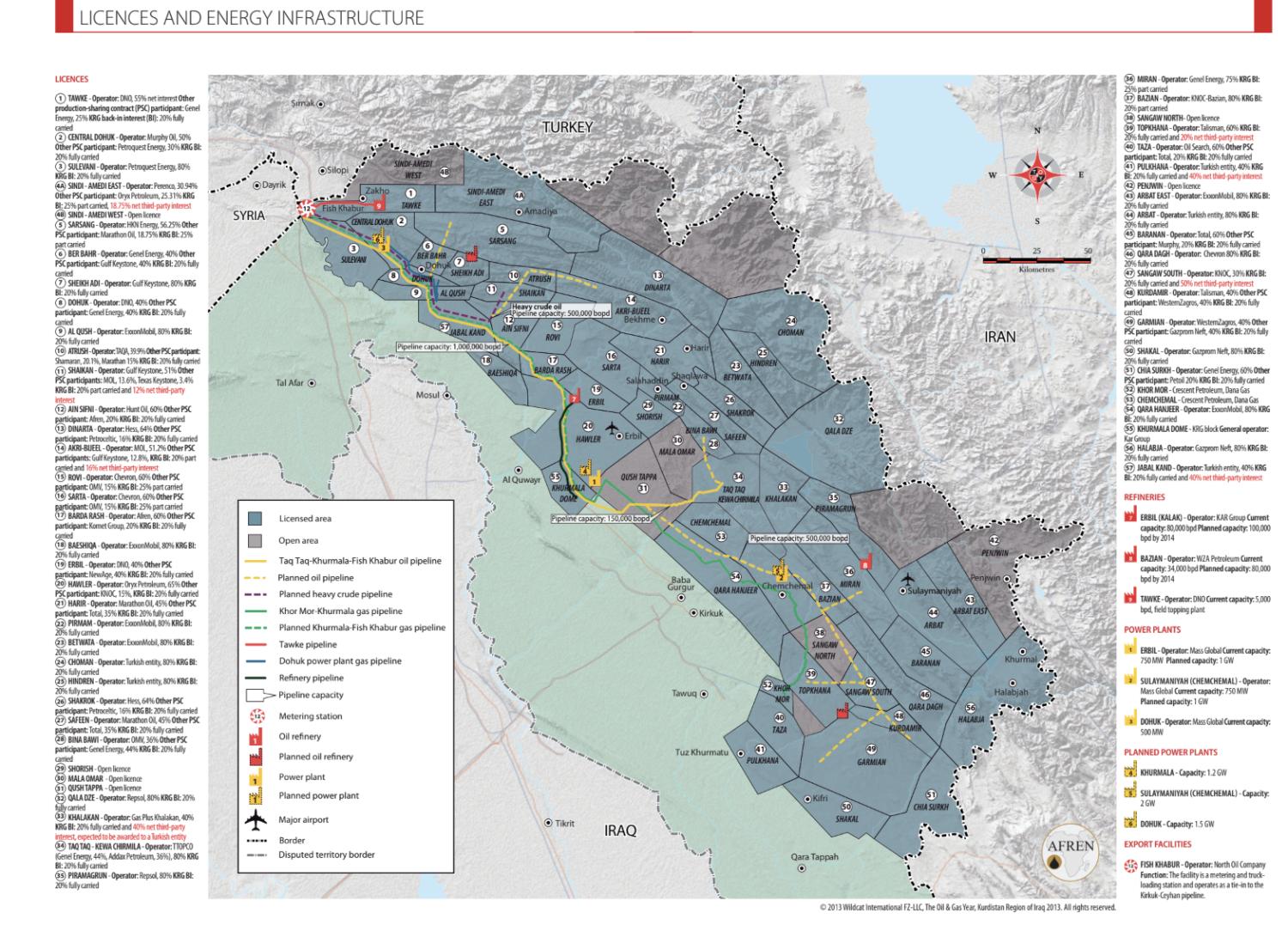

The incident occurred at a particularly sensitive juncture, following the installation of new facilities under the KM250 project, which, according to Dana Gas and Crescent Petroleum, increased Khor Mor’s production capacity to a total output of about 750 million standard cubic feet per day (MMscf/d). This situation illustrates a central paradox in Kurdistan’s energy sector: each advancement in infrastructure and capacity enhances the field’s strategic value while simultaneously increasing the incentive to target it as a means of undermining Kurdistan’s economic consolidation.

The evolving nature of the attacks is not limited to their frequency but extends to their underlying significance. Since 2022, Khor Mor has experienced eleven reported attacks, which, when considered collectively, no longer appear to be isolated security incidents. Instead, they increasingly form part of a broader, coordinated campaign that combines security threats with political, legal, and financial constraints, aiming to prevent the Kurdistan Region from achieving sustainable economic autonomy. Khor Mor has thus become a focal point where energy security, federal-regional power dynamics, and Iraq’s fragmented security environment intersect.

Key factors

The first driver is political: Baghdad’s renewed push to centralize power. As federal institutions have reasserted authority over the past decade, the Kurdistan Region’s independent development model – characterized by attracting foreign investment, signing energy contracts, and rapidly building infrastructure – has increasingly been perceived by some as a threat to the internal balance of power, rather than as a national achievement. A region capable of generating its own power, monetizing its gas resources, and independently managing payrolls gains significant leverage in negotiations over budgets, governance, and political authority. Consequently, the core issue extends beyond pipelines and power stations to whether the Kurdistan Region remains structurally dependent on federal transfers and permissions or attains the economic autonomy necessary to negotiate as an equal.

The second driver is economic and fiscal control over revenue. To maintain Erbil’s dependency, federal authorities have frequently exercised leverage through budgetary mechanisms and administrative barriers. The Kurdistan Region is most vulnerable when reliant on Baghdad for salary payments, public services, and consistent cash flow. In this context, limiting Kurdistan’s ability to generate and manage its own revenue serves as a deliberate source of bargaining power.

Beyond the energy sector, Kurdish producers and manufacturers have consistently faced obstacles accessing Iraqi markets. For example, Kurdish farmers and entrepreneurs have encountered difficulties exporting produce, poultry products, and manufactured goods to other parts of Iraq. Regardless of official justifications, these cumulative measures constrain Kurdistan’s economic opportunities and perpetuate a model in which regional prosperity depends on federal discretion.

The third driver is security fragmentation and the political utility of ambiguity. Iraq’s state apparatus comprises both formal armed forces and influential paramilitary networks operating with varying degrees of operational independence from the formal state chain of command. This structure enables a situation in which violence can influence political outcomes while responsibility remains difficult to assign. For Baghdad, this dynamic allows for plausible deniability, as attacks may be condemned as the actions of outlaws without prompting transparent accountability measures. For militant actors, the incentives are also clear: targeting strategic economic assets in Kurdistan imposes political costs on the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), increases investor risk perceptions, and weakens the regional leadership’s negotiating position, all without necessarily provoking direct confrontation with the federal government.

A fourth driver is strategic signaling to investors. Energy projects in Kurdistan have historically depended on foreign technical expertise and private capital. Repeated attacks on Khor Mor send a message not only to current operators, but also to potential investors across Kurdistan’s economy: progress is vulnerable to disruption, and the state may be unable or unwilling to guarantee operational continuity. This signal is especially powerful when attacks target newly expanded infrastructure. As capacity increases, the opportunity cost of disruption rises, amplifying the deterrent effect on future investment.

A multilayered strategy

All these factors operate as a complex strategy that combines kinetic disruption with institutional constraints. The kinetic component is straightforward: repeated attacks undermine operational reliability. Even when physical damage is minimal, shutdowns, repairs, and safety protocols reduce output, disrupt power generation, and impose ongoing costs. Each incident also forces operators to allocate resources to security, insurance, redundancy planning, and crisis management – resources that would otherwise support expansion, optimization, and new investment.

The institutional layer is subtler and, in many respects, more enduring. Legal disputes, regulatory uncertainty, and budgetary conditions serve as long-term constraints on Kurdistan’s development ambitions. If contracts are subject to challenge, revenues can be withheld, and cross-border export arrangements disrupted. This, in turn, renders the energy sector politically vulnerable despite technical success. In this context, attacks do not need to achieve total destruction; they only need to render progress intermittent, unstable, and costly.

The effectiveness of this mechanism lies in the mutual reinforcement of its layers. Physical attacks, combined with legal and fiscal uncertainty, heighten investor caution, increase capital requirements, and reduce the number of willing partners. Simultaneously, repeated investigations that fail to publicly identify perpetrators or result in prosecutions foster a culture of impunity. Although investigation committees may be established after each incident, the absence of public findings and accountability signals that there are no meaningful consequences for undermining Kurdistan’s critical infrastructure. This dynamic has created a recurring cycle of attack, blackout, committee formation, silence, and repetition.

This pattern takes on added significance when set against the lack of comparable attacks on Western companies involved in gas development in federal Iraq. This has reinforced the perception in the Kurdistan Region that targeting the region’s energy sector constitutes another element of what is perceived as Baghdad’s tacit strategy to undermine Erbil’s economic development. Whether this is accurate, the view itself carries political weight: it reinforces the belief that violence is selectively employed to influence internal power dynamics, which shapes public trust, market behavior, and political expectations.

The impact

The most immediate impact is human. A single strike that causes days-long blackouts leads to rapidly cascading economic and social costs. Factories reduce or halt operations, small businesses lose income, hospitals and public services depend on backup systems, households experience hardship, and public confidence in governance declines. Energy insecurity imposes additional burdens on every sector, particularly in an economy already challenged by fiscal volatility and political competition.

The second impact is strategic, as the attacks exploit infrastructure dependence. Electricity generation is not only a key utility, but also a foundation of political legitimacy. As Khor Mor provides the majority of the region’s electricity, its disruption undermines the KRG’s ability to govern and weakens its negotiating position with Baghdad. Each attack compels Erbil to focus on crisis management at the expense of long-term planning.

The third impact is the increase in risk premiums across Kurdistan. Energy infrastructure projects require long-term investment and stable expectations of continuity. Repeated attacks and a lack of transparent accountability lead insurers, lenders, and contractors to view Kurdistan as a higher-risk environment. This perception raises the cost of expanding fields, financing new facilities, and developing downstream industries reliant on consistent gas and power supplies. Consequently, development slows, even when resources and technical plans are available.

The fourth impact is national and systemic. Khor Mor represents not only a Kurdish asset, but also a potential Iraqi energy resource. Iraq’s broader energy future relies on expanding domestic gas use, minimizing waste, and maintaining a stable electricity supply. Permitting repeated disruptions of a major gas project without public accountability signals that Iraq as a whole faces challenges in safeguarding strategic infrastructure. This undermines the country’s appeal to investors beyond Kurdistan and reinforces the perception that political competition outweighs national planning.

Finally, the attacks intensify mistrust between Erbil and Baghdad. In Kurdistan, each incident reinforces perceptions that Baghdad does not prioritize the region’s development and may even favor continued dependency. Conversely, some policymakers in Baghdad regard Kurdistan’s energy model as a challenge to constitutional order and revenue management. As these narratives become entrenched, opportunities for compromise diminish, reducing the prospects for a collaborative national energy strategy.

What should be done?

If Iraq is committed to energy security and national cohesion, protecting Khor Mor must become a joint federal and regional priority rather than a site of proxy conflict. This requires establishing a credible security framework for critical infrastructure and incorporating integrated intelligence, counter-drone capabilities, and coordinated response protocols between federal and regional forces. Protection should be institutionalized, adequately resourced, and shielded from political competition, rather than being reactive or improvised after each incident.

Accountability is the second requirement. Investigation committees that fail to produce public findings or prosecutions inadvertently incentivize repeated attacks. While transparency need not compromise sensitive intelligence, it does require a clear process linking incidents to attribution and legal consequences. Without such measures, markets will continue to anticipate future attacks, and investment decisions will reflect this expectation.

Lastly, reducing the potential political gains from such actions could diminish the underlying incentives for the attacks. This requires a durable federal and regional agreement on energy governance and public finance, providing predictability regarding revenues, budgets, and the legal status of contracts. As long as Kurdistan’s economic autonomy is perceived as a zero-sum contest, strategic assets will continue to be targeted as instruments of leverage.

is the Barzani Scholar-in- Residence at American University’s School of International Service, where he directs the Global Kurdish Initiative for Peace.