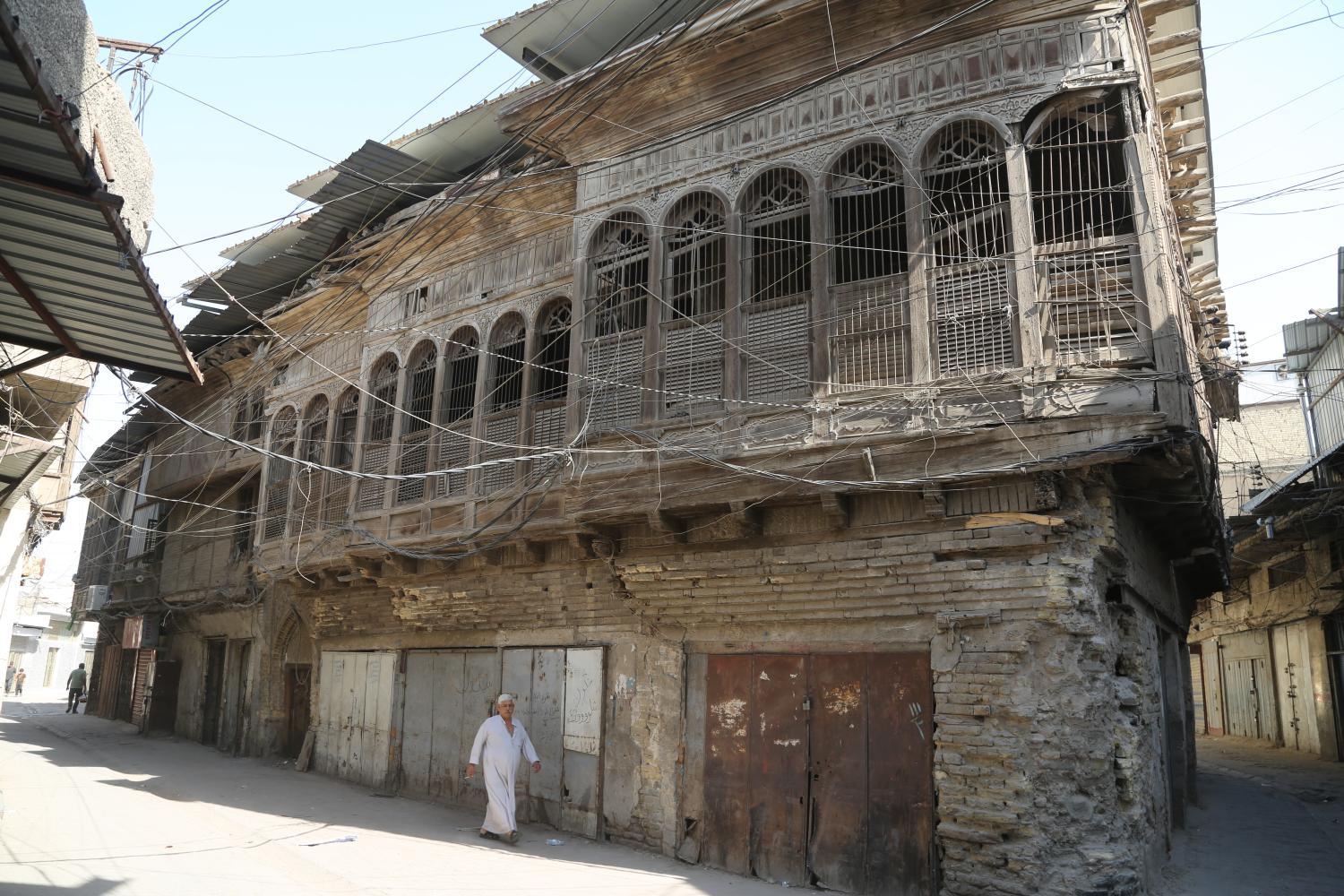

Leaning against the walls of abandoned houses, their carved wooden shanashil balconies fallen into disrepair since their Jewish owners left more than seven decades ago, octogenarian Abu Haider walks slowly through an alley in Baghdad’s Qanbar Ali neighborhood. He heads toward Hanoun Market – named after one of its most prominent Jewish shopkeepers – to buy his needs at a careful pace.

“Here we grew up; we played with our Jewish friends without problems. Politics, conflicts, and hate separated us,” he says. “They were uprooted by arbitrary decisions, and what remains is only their heritage.”

“Look at the artistry,” Abu Haider says with admiration, gazing at the beauty of the old homes around him, a reminder of hearts that wished to stay but were forced to leave. Today, most of the houses have turned into garbage dumps. “There was affection and peace here. Everyone respected the feelings and sanctities of the other. We shared joys and sorrows. They were peaceful people, but charges were fabricated against them, and they were subjected to barbaric attacks that terrified them.”

An alley in Baghdad's Qanbar Ali neighborhood named after the Torah (Photo: Hemin Baban).

The Holocaust of Iraq

Age has not erased from Abu Haider’s memory the image of his neighbor, Salima Lawi, the Jewish seamstress of the district. “She always exchanged dishes and meals with the neighbors, especially during Ramadan, easing the burden of fasting for my mother,” he recalls. “Whenever I remember her, I pray that her resting place is paradise.”

In June 1941, Baghdad’s Jews faced their most violent assault, coinciding with Shavuot, the holiday marking the Torah’s descent at Mount Sinai. During those two days, 179 Jews were killed, and 1,500 homes and shops were looted in what came to be known as the Farhud, or the Holocaust of Iraq.

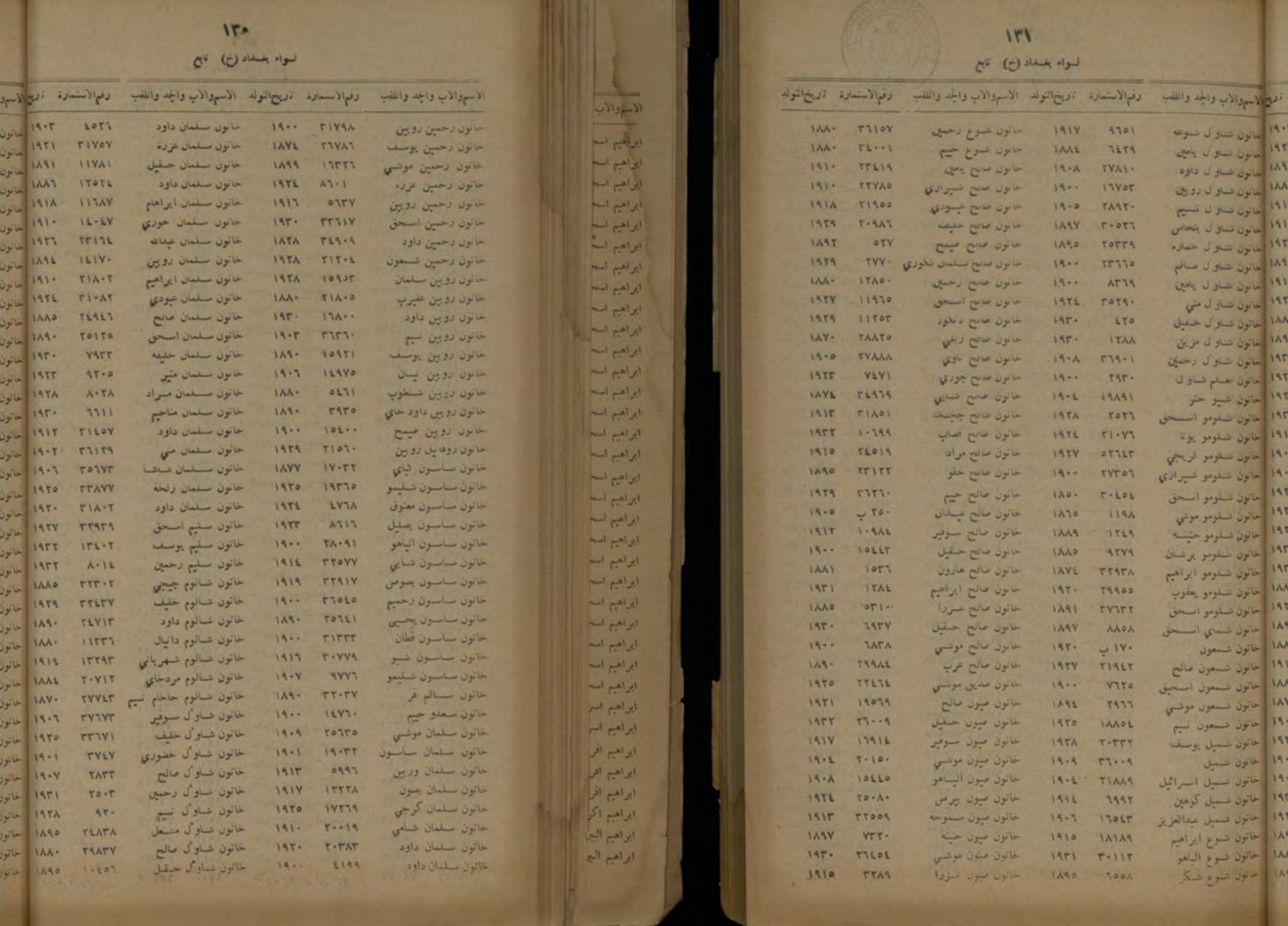

Fanatical nationalist currents and their newspapers stoked hatred, which peaked with the announcement of Israel’s establishment in 1948. Then came the stripping of Iraqi Jews of their citizenship, and the decision to expel around 135,000 of them under the “Denaturalization Law” No. 1 of 1950. Their properties were seized under later legislation, marking the start of mass expulsion.

Seventy-five years ago, an Iraqi government decision ended the presence of a Jewish community that had lived in Mesopotamia for more than 2,600 years, following the tragedy of the Farhud, the so-called Holocaust of Iraq.

Neglected by authorities, the Jewish heritage in Iraq is falling into disrepair (Photo: Hemin Baban)

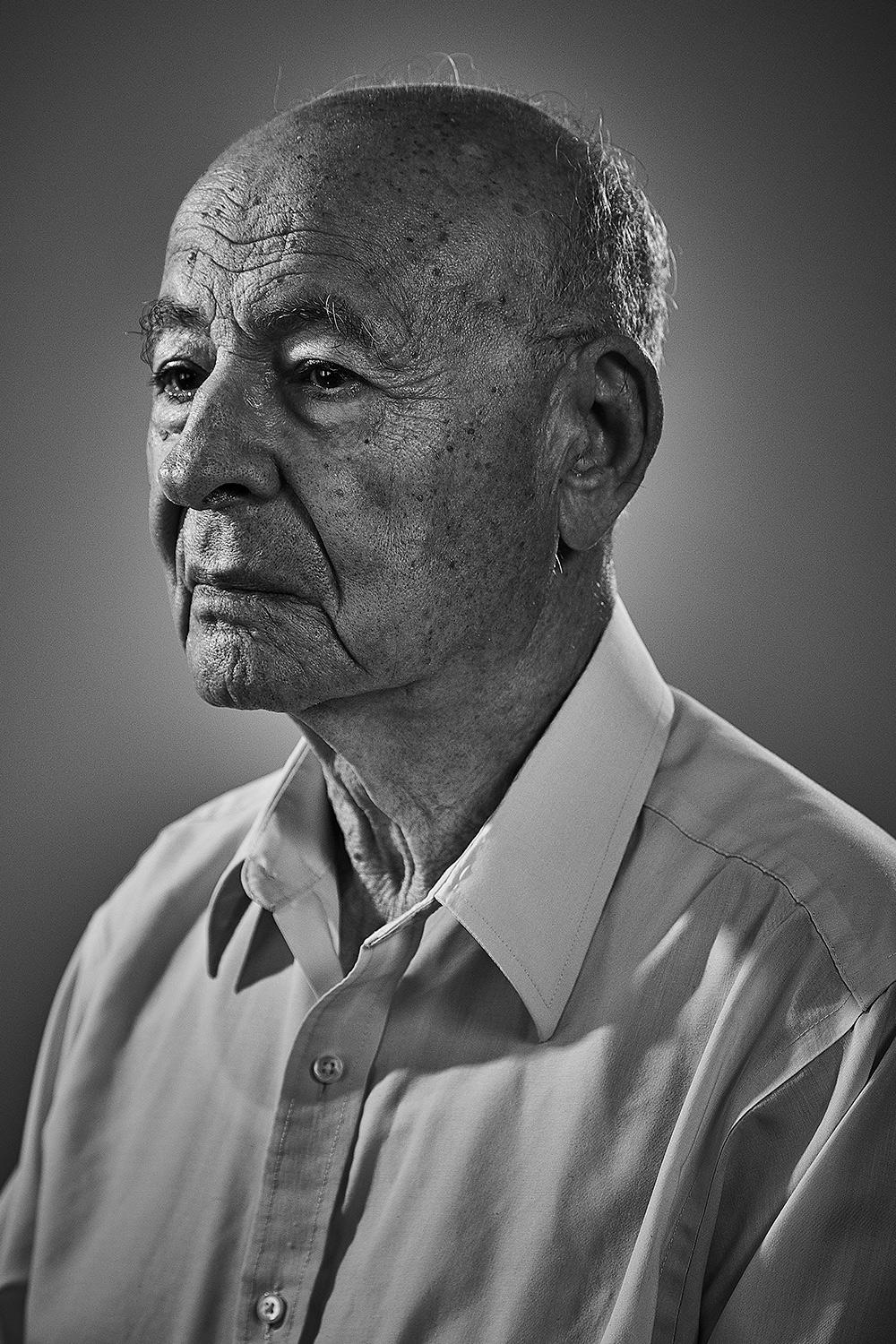

A survivor’s story

Another octogenarian, Iraqi Jew Sami Surani, survived the massacre with his family. He recalls the details of those nights: “We were at my grandfather’s house. My father and uncle locked and bolted the door tightly, stacking heavy furniture against it to keep attackers out. From outside, we heard women and children screaming as they were killed and assaulted.”

He still remembers his father’s words that night: “It is a shame we bring children into this world,” the man wept. “What sin have children committed to be born into this cruel world?”

“Through the windows, we saw Jewish shops looted and destroyed,” Surani relates. “We had nothing but tears and prayers for God’s mercy. We lived in constant fear for over two months, never leaving the house.”

Sami Surani, a survivor of the Jewish massacre in Iraq, known as Farhud

The massacre coincided with the Jewish festival of Shavuot and with the return of Regent Abd al-Ilah to Baghdad. “The attackers thought the Jewish gathering for traditional prayers by the Tigris was to welcome the regent,” Surani recalls. “They threw some into the river, stormed buses, and killed Jews inside.”

During the Farhud, Jewish homes in Baghdad were marked in red, making them easy targets for mobs to storm, kill residents, loot property, and assault women and girls, with the complicity of some police officers, according to Surani.

Meir Taweig Synagogue, one of the oldest synagogues in Iraq. It served as a primary location for documentation of the Iraqi Jews who fled Iraq after the notorious Farhud massacre (Photo: Hemin Baban)

He confirms, citing a document from the British High Commissioner in Baghdad, that the massacre’s victims numbered around 2,000 Jews.

At the same time, he remembers Muslims who risked their lives to save Jews. “Some Muslims, many of them Kurds, fought off mobs to protect Jews. We honor them, just as we honor General Mustafa Barzani, who openly declared that Jews must be protected and that no one should dare harm them. Later, his son Masoud Barzani, and the Kurds generally, also helped many Jews escape Iraq, something Jews remain grateful for to this day.”

The organization Justice for Jews from Arab Countries values Jewish-owned assets and institutions at around $34 billion (Photo: Hemin Baban)

Only five remain

Iraq’s Jews are among the world’s oldest Jewish communities, tracing their roots back to the Assyrian exile of the Kingdom of Israel in 722 BC, and the Babylonian exile of Judah in 586 BC, when tens of thousands were deported from Jerusalem to settle in Babylon and Kurdistan. But in the 20th century, they faced systematic persecution that reduced their numbers from about 140,000 to just five by 2024, according to the organization Justice for Jews from Arab Countries.

Benjamin Elias, in his sixties, from a well-known philanthropic family, is one of those who refused to emigrate. He chose to remain in what he calls “the land of religions, temples, and prophets,” rich in Jewish heritage. He complains of harassment fueled by politicized propaganda targeting Jews and other minorities.

Today Elias lives quietly in a Baghdad neighborhood, keeping to a small circle of acquaintances, like the few remaining Jews. He performs his rituals at home, away from closed synagogues, visits his family graves in secret, and laments a society shaped by decades of state-led incitement against minorities, especially Jews.

According to Iraq’s first census in 1920, Jews made up 3.1% of the population – over 87,000 people. By 1947, the proportion dropped to 2.6%. After the mass expulsion in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah (named after two prominent Jewish figures), it fell to about 0.08%, or 10,000-12,000 people.

The Tomb of Prophet Nahum after it was renovated by the Kurdistan Regional Government (Photo: Hemin Baban)

The Jews of Kurdistan

Iraq’s 2005 constitution made no mention of Jews or their religion. Nor were they included in the 2012 law regulating Christian, Yezidi, and Mandaean endowments. They were also excluded from regaining Iraqi nationality under the 2006 Nationality Law, while hate speech from clerics and politicians went unpunished.

In contrast, the Kurdistan Region officially recognized Jews within the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs in 2015, under the Law on the Protection of Components No. 5, which encourages the return of displaced groups and guarantees their rights.

This representation is headed by 62-year-old Sherko Osman, a Jew from Erbil whose grandfather was a rabbi. “The history of Kurdistan’s Jews stretches back 25 centuries,” Osman says. “We freely practice our rituals and daily life, facing no restrictions. We are respected in our identity.”

A Jewish man praying at the Tomb of Prophet Nahum (Photo: Hemin Baban)

Most Jews in Kurdistan today are descendants of families scattered by expulsion or those who concealed their faith for safety. Osman notes full coordination with the regional government to preserve Jewish heritage sites, such as the shrine of the prophet Nahum, alongside other ongoing restoration efforts.

Ranjdar Cohen, who leads the nongovernmental organization Aramik, affirms the national belonging of Kurdistan’s Jews. “We are not concerned with politics. We are an ancient religious community, proud of our faith and culture, loyal to the land where we live. Yet some exploit our cause by linking us to Israel, sowing division among Iraqis.”

“There are around 2,500 Jews in Kurdistan, enjoying greater freedom here,” he adds. “We call on both the federal and regional governments to protect Jewish heritage and to ease visits by Jews to Iraq and their sacred sites.”

The Jewish cemetery in Baghdad's Habibiyah neighborhood contains nearly 4,000 graves, including victims of the notorious Farhud massacre (Photo: Hemin Baban)

A heritage crumbling without rescue

In Baghdad’s Bataween district, once home to Jews, visitors now see dozens of abandoned houses and buildings fallen into ruin. Among the few remaining landmarks is the Meir Tweig Synagogue, which in 1950 became the registration center for Jews preparing for emigration.

There are no precise statistics on Jewish properties in Iraq, but estimates purport that there are 12,000 abandoned properties. The organization Justice for Jews from Arab Countries values Jewish-owned assets and institutions at around $34 billion, left behind by 135,000 Iraqi Jews.

The Jewish archive that was moved to the U.S. after the liberation of Iraq in 2003. The documents were kept in a basement during the rule of Saddam Hussein.

The Jewish Heritage Foundation, with the American Society for Overseas Research, documented in 2020 about 297 Jewish heritage sites in Iraq. Only 30 remain today, 21 of them in extremely poor condition. These included synagogues (40%, 118 sites), neighborhoods (32%, 96), and schools (16%, 48). A full 89% were deemed “extinct.”

Another site is Baghdad’s Habibiyah Jewish cemetery in Sadr City, with 4,000 graves, including rabbis and Jews executed as “Israeli spies.” The cemetery itself tells their tragic story. It was established in 1962 after a government order moved over 3,000 Jewish remains from the Nahda cemetery to make way for the never-built Baghdad Tower project. The land later became a parking lot called “Karaj al-Nahda.”

Two pages from a long list documenting Jewish people who were stripped of Iraqi citizenship under Law No. 1 of 1950.

Niran Bassoon’s mission: Memory in exile

Though exiled from Iraq at the age of 16, Iraqi Jew Niran Bassoon, who is now 68 and in London, did not surrender to despair. Instead, she devoted her life to documenting the history of Iraqi Jews and reviving their nearly erased heritage.

Eight years ago, she turned part of her home into a small studio, launching her YouTube channel Noor W Nar (“Light and Fire”), broadcasting dialogues with Iraqi Jews, many of whom were witnesses to the Farhud and other expulsions. Alone, without a team, she has published over 150 interviews, making her channel a platform followed by Iraqis of all backgrounds.

Niran Basson, an Iraqi Jewish activist exiled at the age of 16, now lives in London.

Her home is also filled with photos documenting Jewish life in Iraq. Her channel has become a window to a community that once played a pivotal role in the nation’s story before being erased by fanaticism and conflict.

Her family had resisted leaving Iraq during the expulsions of 1950-1951. But in August 1973, harsh circumstances forced them out, and her passport was stamped “one-time exit only,” banning her return after her Iraqi nationality was stripped. “Iraq, the birthplace of my ancestors, is still a big part of my life,” she says sorrowfully. “I grew up loving it despite the distance. I inherited my father’s passion for journalism and for documenting the role of Jews in Iraq, that’s what inspired my channel.”

Salim Bassoon, her father, was a pioneer of Iraqi journalism in the last century, repeatedly arrested and exiled. After decades of resilience, he finally left to protect his family. “The Kurds helped save many Jews, helping them cross the border to Iran,” Niran recalls. “But returning to Iraq is now impossible. At best, I dream of visiting, without having to hide my Jewish identity.”

Before we leave Qanbar Ali in Baghdad, Abu Haider raises a question to the Iraqi government on behalf of many: “How long will Jewish heritage remain neglected in Iraq? And how long will they be forbidden to return?”

Madrash School (built in 1839) was one of the prominent religious schools for the Iraqi Jews (Photo: Hemin Baban)

A Kurdish journalist who has worked for a number of local and international media institutions.