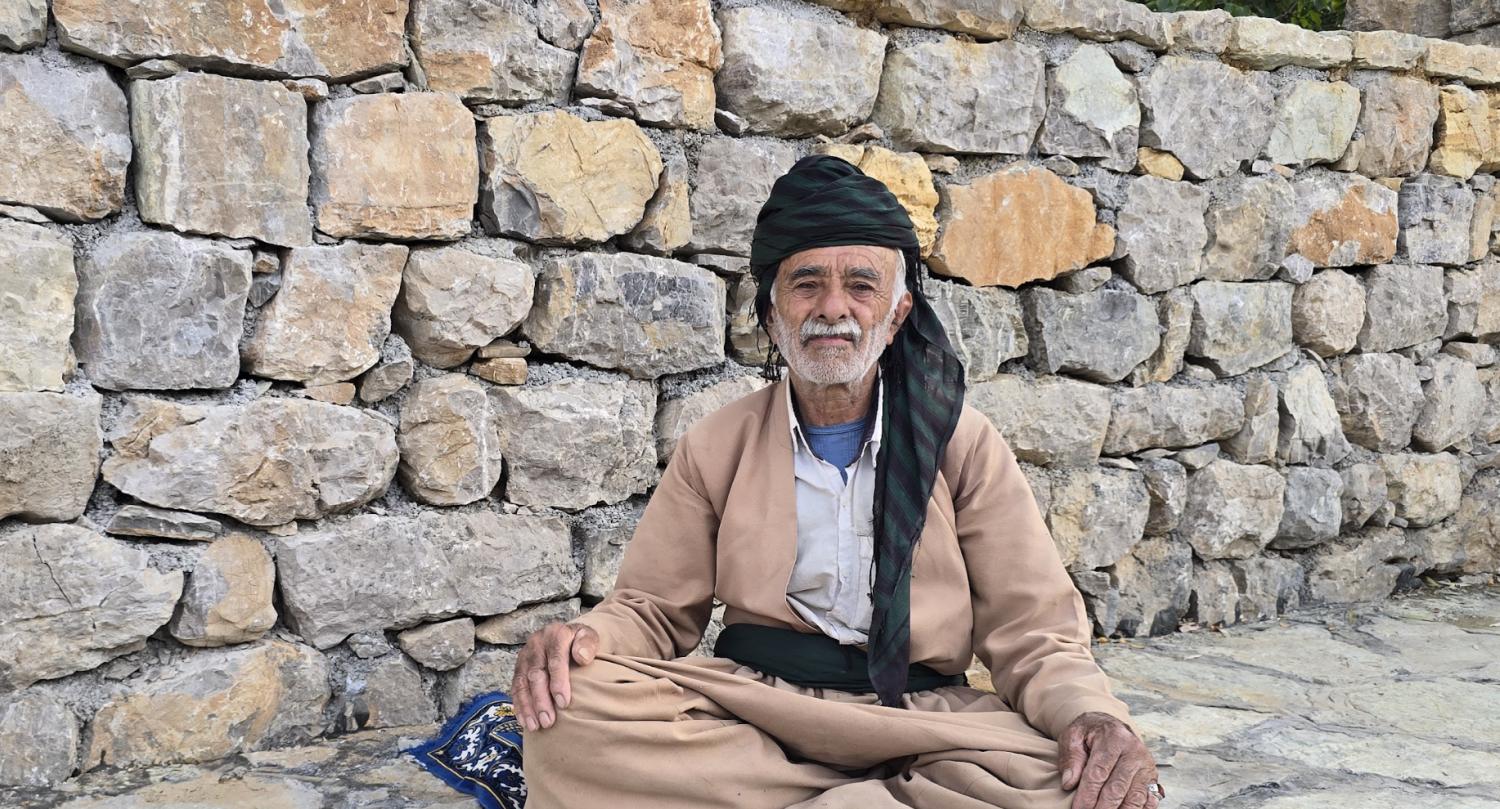

Hawraman, a mountainous area stretching between Southern Kurdistan (the Kurdistan Region of Iraq) and Eastern Kurdistan (northwestern Iran), is a region rich in both culture and nature, and its people maintain a deep attachment to the landscape.

Most houses in Hawraman are carved into the steep slopes of the Zagros Mountains, and stone is more than a building material; it is a way of living that continues to define how people survive, gather, worship, and imagine their place in the world. While many rural cultures have shifted toward concrete and modern construction techniques, Hawraman remains one of the few places where architecture and landscape still speak the same natural language.

In 2021, UNESCO recognized Hawraman as a World Heritage Site – not for a single monument, but for a cultural system: an architecture born from necessity and refined into an identity that is reflected in homes, mosques, paths, terraces, and the traditions that continue to keep this indigenous Kurdish community together.

From geography to agriculture

Hawraman’s human settlements stretch across steep, narrow slopes where conventional building is next to impossible. Flat land is rare, its winters are harsh, and its summers dry. Out of these natural constraints, the Hawrami people developed a vertical architecture that feels both ancient and intelligently adapted. And, importantly, it remains remarkably eco-friendly.

The houses are stacked in rows, with each roof serving as the courtyard of the home above it. From a distance, villages like Tawella, Byara, and Uraman Takht look almost sculpted into the mountainside. This system, born from a lack of space, became an architectural signature. All of this creates an auditorium-style spectacle where the music of nature, history, and culture shapes a harmonious symphony of what it means to be Kurdistani.

Inside, the homes are surprisingly comfortable. The secret lies in the stone walls – 70-90 cm thick – that help sustain warmth indoors during the cold seasons and keep the interior cool during summer heat. These walls are made of local stone, gathered from the surrounding mountains, and shaped by hand.

Dry-stone masonry: The technique that keeps Hawraman standing

One of the most distinctive features of Hawrami architecture is the continued use of dry-stone construction, known locally as weshka-chin. Traditional building techniques use no concrete, cement, or binding material of any kind. Stones are placed and balanced with care, relying on gravity, friction, and the hands of skilled masons.

For generations, Hawrami builders have mastered the ability to read a stone, its weight, angle, and strength, and know exactly where it belongs. A few tools, a strong eye, and patience form the foundation of this craft.

This method may look simple, but it has kept entire villages standing for centuries. Dry-stone walls move slightly during earthquakes, breathe during changes in temperature, and drain water naturally during heavy rain – advantages that modern materials often lack in mountainous terrain.

In Hawraman, engineering and tradition are inseparable and indistinguishable.

The social rhythm of mosques and gathering spaces

Stone does more than hold houses together. It shapes how Hawrami communities gather and connect.

Mosques, besides their religious status and spiritual importance, are social hubs built to endure and to help sustain the local worldview. Every village has a stone mosque, which is the emotional and social core of the community. Thick walls keep the prayer hall warm in winter and cool in summer. Carved stone pillars hold doors and porticos that have stood through generations.

Beyond prayer, these mosques are where people meet to discuss village matters, settle disputes, make collective decisions, and share news. In many ways, stone architecture protects not just the building, but the continuity of Hawrami social life.

Alongside mosques, pathways and bridges help keep the mountains connected. Life in Hawraman has always required movement across rivers, cliffs, and narrow passes. Old stone bridges, such as the well-known Galoz Bridge, were built entirely by hand and remain stable despite the region’s shifting weather.

Narrow mountain paths called qucha-berd were laid with stone slabs to create safe routes for people and animals, connecting villages, markets, farms, and family networks long before modern roads reached the region.

Hawrami tea houses, like other structures, are often built from stone and serve as early cultural centers of the villages. Men gather to talk, recite poetry, exchange news, or sing traditional Hawrami songs.

Nearby, public basins – small stone pools linked to village mosques – play a similar social role. They provide water, as well as space for reflection and routine. Stone gives these spaces a sense of permanence.

Terraced agriculture: How stone enabled farming

Agriculture in Hawraman is a story of creativity. With almost no flat land for farming, people built stone terraces with long retaining walls that hold soil in place and turn steep mountainsides into cultivable land.

These terraces allow for the planting of pomegranates, grapes, walnuts, figs, and seasonal crops. Without stone terraces, farming here would collapse. Without them, Hawraman’s economy and food traditions would not survive.

Terraces also protect the environment. They prevent soil erosion, regulate water flow, and preserve mountain biodiversity. Each terrace is a quiet reminder that Hawraman’s culture is indeed in partnership with nature.

Stone as identity: A culture to last

What makes Hawraman unique is not simply that it uses stone, but rather how it uses it. Stone is woven into identity, into how people live, farm, gather, and pass culture to the next generation. Modern materials have reached Hawraman, but the core relationship between people and stone remains.

In a world that has abandoned many traditional building methods, Hawraman stands as proof that old techniques can be both functional and beautiful, and sometimes more sustainable.

Hawraman is not just a mountainous region. It is a living archive of adaptation, skill, and memory. Every stone in its houses, terraces, mosques, paths, and bridges carries a story of survival and creativity. The region’s architecture is not simply historic; it is still alive, still in use, still shaping daily life.

And that is why Hawraman continues to feel like a place where the past and present walk side by side, inspiring the future – held together by the simplest and strongest material: stone.

A Kurdish photographer and journalist.