In an age when the word “Kurd” is still uttered in the corridors of power as though it were a clerical error on the map of the Middle East, there arrives a book that refuses to ask for recognition and instead boldly takes the witness stand. Salam Abdullah’s Ember Revival is not a fragile memoir wrung from the sleeve of victimhood. It is a clear, steady indictment of the Ba’athist laboratory of human annihilation and, more triumphantly, a blazing tribute to the one thing that the laboratory could never kill: the collective Kurdish spirit.

What begins as the story of one young man betrayed, caged, and beaten up by a regime that regarded dignity as a capital offense, ends as an unflinching demonstration that when a state sets out to atomize a people, it merely builds them the forge in which a harder, brighter nation is created.

Abdullah’s autobiographical novel is certainly a personal chronicle, but it is also a vital historical testimony to the Kurdish struggle against Iraq’s Ba’athist terror machine. The prose is unflinching, rejecting sentimentality for forensic precision. Its protagonist, Soran Ahmad, is betrayed by a friend, tortured at a “black site” in Sulaymaniyah, then dispatched to the notorious Hai’a Prison in Kirkuk – a terminal station for political prisoners. What follows is a remarkable escape to the Peshmerga, a fugitive odyssey across hostile borders into Iran and Turkey, and a final flight to Syria.

Ember Revival dissects the mechanics of state oppression while celebrating the unbreakable Kurdish spirit. Abdullah exposes the regime’s meticulous cruelty, met everywhere by an equal force of solidarity and dignity, turning the anatomy of terror into the anatomy of a people’s will.

The architecture of terror

The Ba’athist prison is no chaos of violence but a calculated laboratory of dehumanization. Abdullah’s clinical descriptions of Hai’a force the reader to confront the system rather than merely flinch at its pain. Torture began with nature itself weaponized: prisoners bound on thorns beneath the August sun to induce dehydration and heat sickness. Relief became another torment, as prisoners were dragged from searing heat into air-conditioned cold to shatter the mind.

Physical methods were precise: suspension by the arms; falaqa (beatings administered on the soles of the feet); electric shocks that made the brain feel ready to explode. Yet the pressure meant to crush the spirit forged a fighter instead. The cell designed as a tomb became the womb of Soran’s liberation.

Borders in the novel are colonial wounds turned into instruments of oppression. Every crossing, for safety, medicine, or logistics, was a lethal gamble. Escape to Iran offered momentary relief, but agreements allowed repatriation. One Peshmerga, Khasraw, chose suicide over the risk of breaking under torture.

While seeking treatment in Turkey, Soran and his group walked into a planned ambush; an Iraqi passport instantly transformed him from illegal migrant to “rebel.” Sentenced to deportation and death, he escaped in Cizre, aided by strangers, crawling under razor wire – a brutal emblem of Kurdistan’s dismemberment. These frontiers echoed the psychological walls the Ba’athist regime tried to raise inside its prisons.

Contradicting the state’s project of isolation, Ember Revival insists survival is communal. In Hai’a, prisoners aligned stories in secret and tended one another’s wounds, with cellmates massaging beaten feet in quiet rituals of defiance. An elder named Sharif persuaded them to forgo suicidal revolt and preserve the flicker of hope. The Peshmerga embodied this collective covenant: ordinary people on a “holy path” of sacrifice.

Betrayal – by regime-recruited Jash militias or teenage informants – remained a constant threat, making trust the resistance’s rarest currency.

Understanding the nature of fire

Salam Abdullah has crafted a literary testament that transcends memoir. The regime’s methods, from sensory assault to barbed-wire borders, formed one coherent project of atomization.

The Kurdish response was the opposite: human connection rebuilt in the darkest cells; a borderless identity reaffirmed in the mountains. The book’s triumph is its insistence that the fight was for the survival of humanity itself – not merely bodies that breathe, but souls that remain free.

In the end, the barbed wire, the electric prods, the weaponized sun, the borders drawn by drunken colonial clerks – all failed. The Ba’ath Party turned Kurdistan into a theater of pain, expecting to break any remnant of hope. Instead, it produced the Peshmerga, the underground solidarity of Hai’a, the old man who chose life over the relief of death, and this book: a grenade rolled back across the decades with the pin already pulled.

Ember Revival does not plead for sympathy; it records, with lethal calm, that the Kurdish spirit passed through the furnace and emerged not as slag but as steel – and that any empire that believes it can extinguish a people by blowing on the embers has mistaken the nature of fire.

Salam Abdullah, 2023, Ember Revival. Erbil: Khaney Culture.

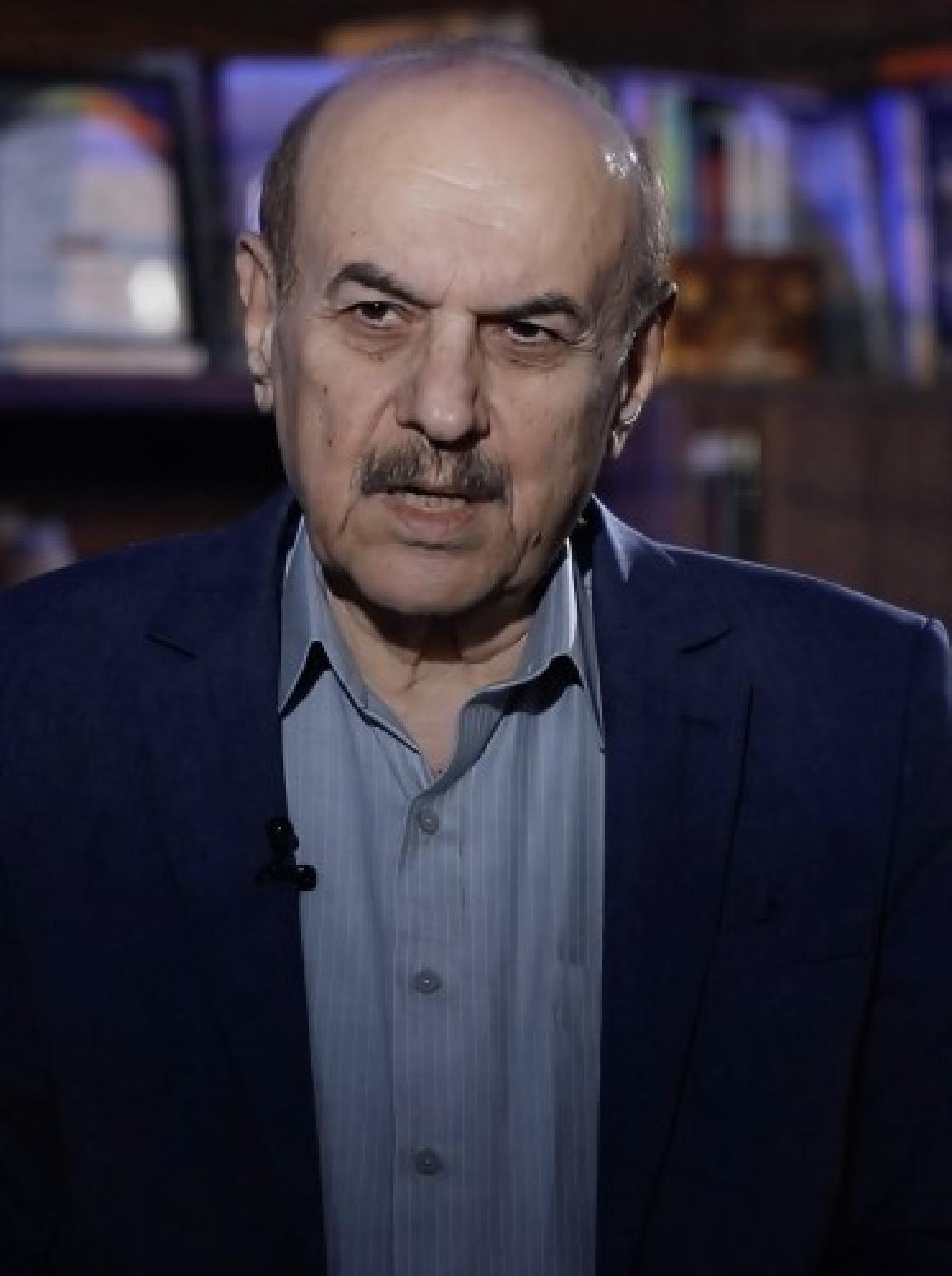

Political scientist. Emeritus Vice Chancellor of University of Kurdistan- Hewlêr, former KRG spokesman and advisor.