This essay is an excerpt from Bernd Lemke’s forthcoming monograph Deutsche und britische Orientreisende 1899-1914 (German and British Travelers to the Orient, 1899-1914). For detailed quotations and references, please consult the published volume upon release.

Martin Hartmann was a pioneer of modern Islamic studies and one of the leading Orientalists of his time. Born on December 9, 1851, in Breslau (today’s Worclaw, in southwestern Poland), he was the son of a Mennonite preacher and initially studied theology before turning to Oriental languages. After obtaining his doctorate, he entered the diplomatic service of the German Empire, which had been founded in 1871, spending considerable time in Beirut, Lebanon. When he left the service in 1887, he began teaching Arabic at the Seminar for Oriental Languages in Berlin at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat (today’s Humboldt University), a position he held until his death in 1918.

Throughout his career, Hartmann published an extensive body of scholarship and frequently commented on political developments in the Ottoman Empire and the broader region. His perspectives developed in the context of Germany’s increasing expansionist foreign policy, particularly its efforts at pénétration pacifique in the Ottoman Empire and the growing desire for at least indirect rule or influence there. In this area, Hartmann emerged as a proponent of liberal imperialism.

Orientalism and its discontents

Hartmann was sharply critical of the Ottoman Empire. Over time, he came to deny its political legitimacy and right to rule over the empire’s subject peoples: Albanians, Arabs, Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Kurds, and Syrians. He believed these groups, supported by their “national consciousness,” their languages, and what he regarded as their superior culture and intellect compared to the Turks, were striving to shake off the “Turkish yoke” and embrace the progressive achievements of the European Kulturstaaten (cultural states).

His fundamental stance remained unchanged during World War I, even after the Ottoman Empire became Germany’s ally in 1914. Although his tone grew more conciliatory and he appealed for unity within the empire, he still doubted its future viability. Depending on the political moment, he alternated between envisioning the empire’s dismantling and proposing a federal system.

Hartmann’s image of the Kurds

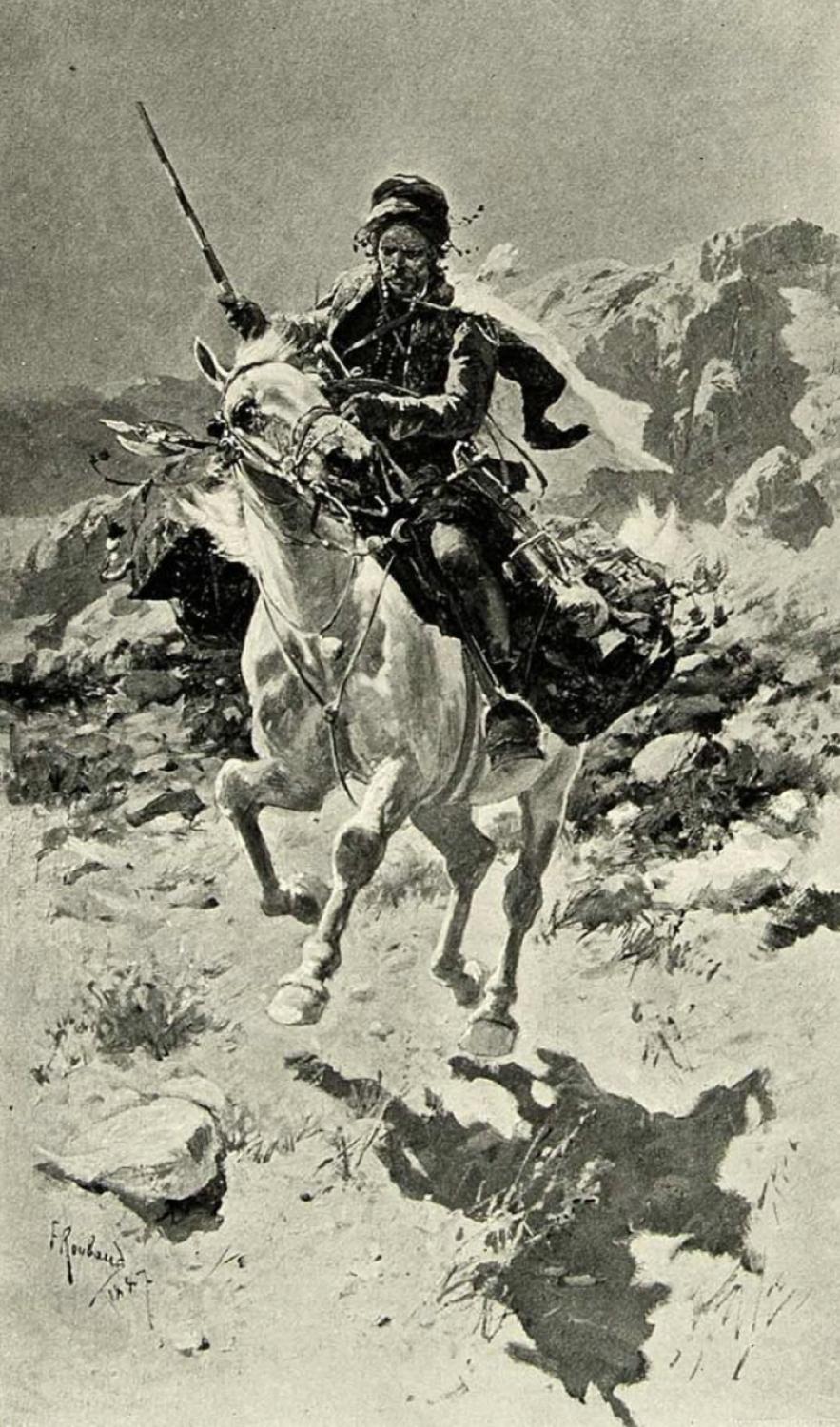

Among the peoples ruled by the Ottomans, Hartmann singled out the Kurds for praise. He regarded them as “vital and vigorous,” endowed with significant cultural potential, and therefore well positioned for a future beyond Ottoman rule. He had previously visited one of their central settlement areas – the region of Botan – and published a detailed account of his observations.

Hartmann offered no substantive discussion of their origin and their “racial” classification, nor did he explicitly endorse the contemporary narrative that identified the Kurds as belonging to the Indo-European language and ethnic group (Aryans) and therefore closer to the Germanic peoples than to Turks or Arabs.

Instead, he described the Kurds as one of the “marginal peoples” oppressed by the Turks, who needed to be protected and supported and would, once encouraged, contribute meaningfully to what he understood as “the work of civilization.” In his view, the Kurds possessed notable intelligence, a constructive, practical disposition, and a bold character. “The Kurd is something between the temperamental, agile, quick-witted and also overly cunning Arab and the sluggish, lazy-minded, slow-thinking Turk. Once this nation has the right man, it will amaze the world with its strength and the energy with which it integrates itself into contemporary world culture.”

Oskar Mann and parallel assessments

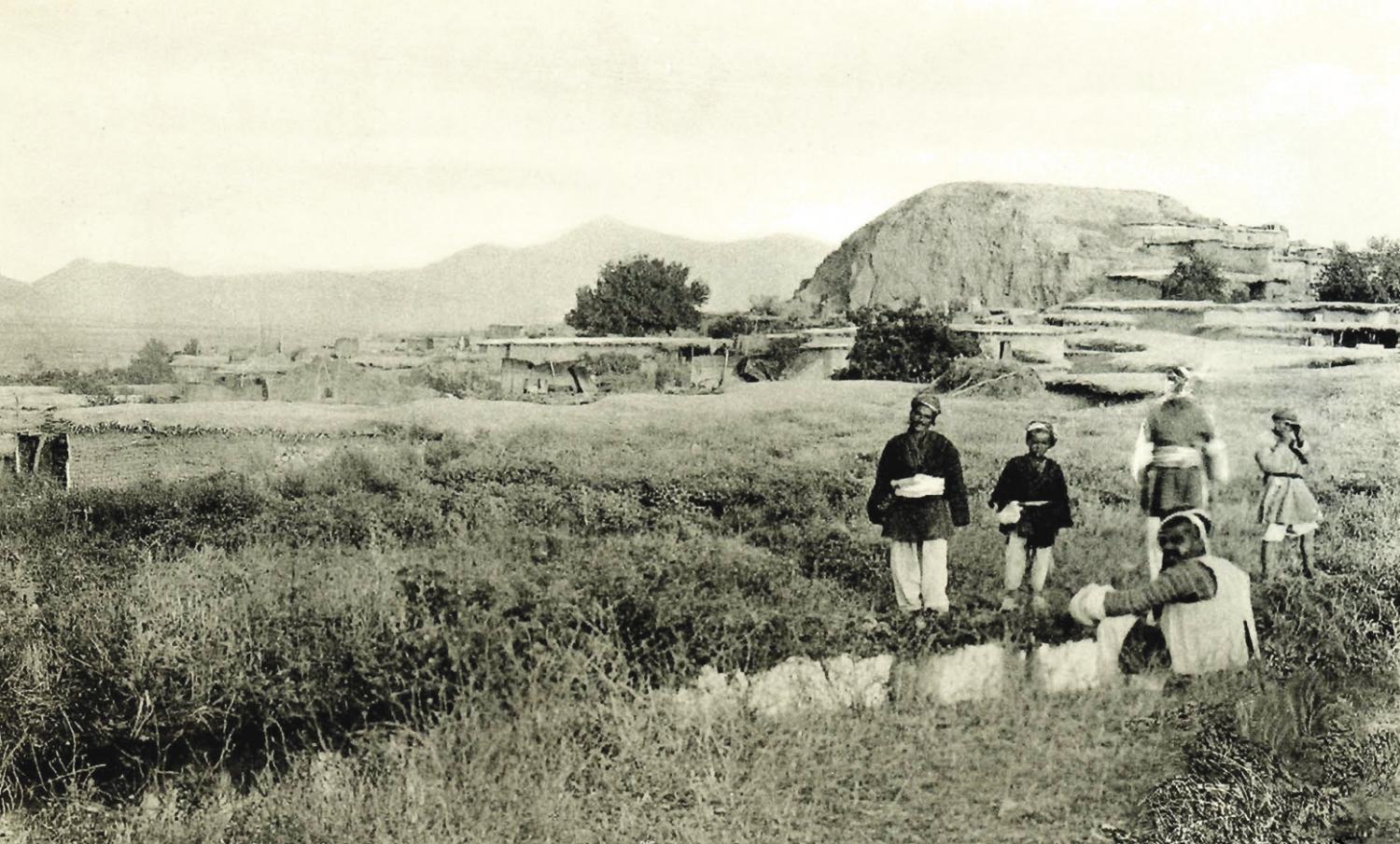

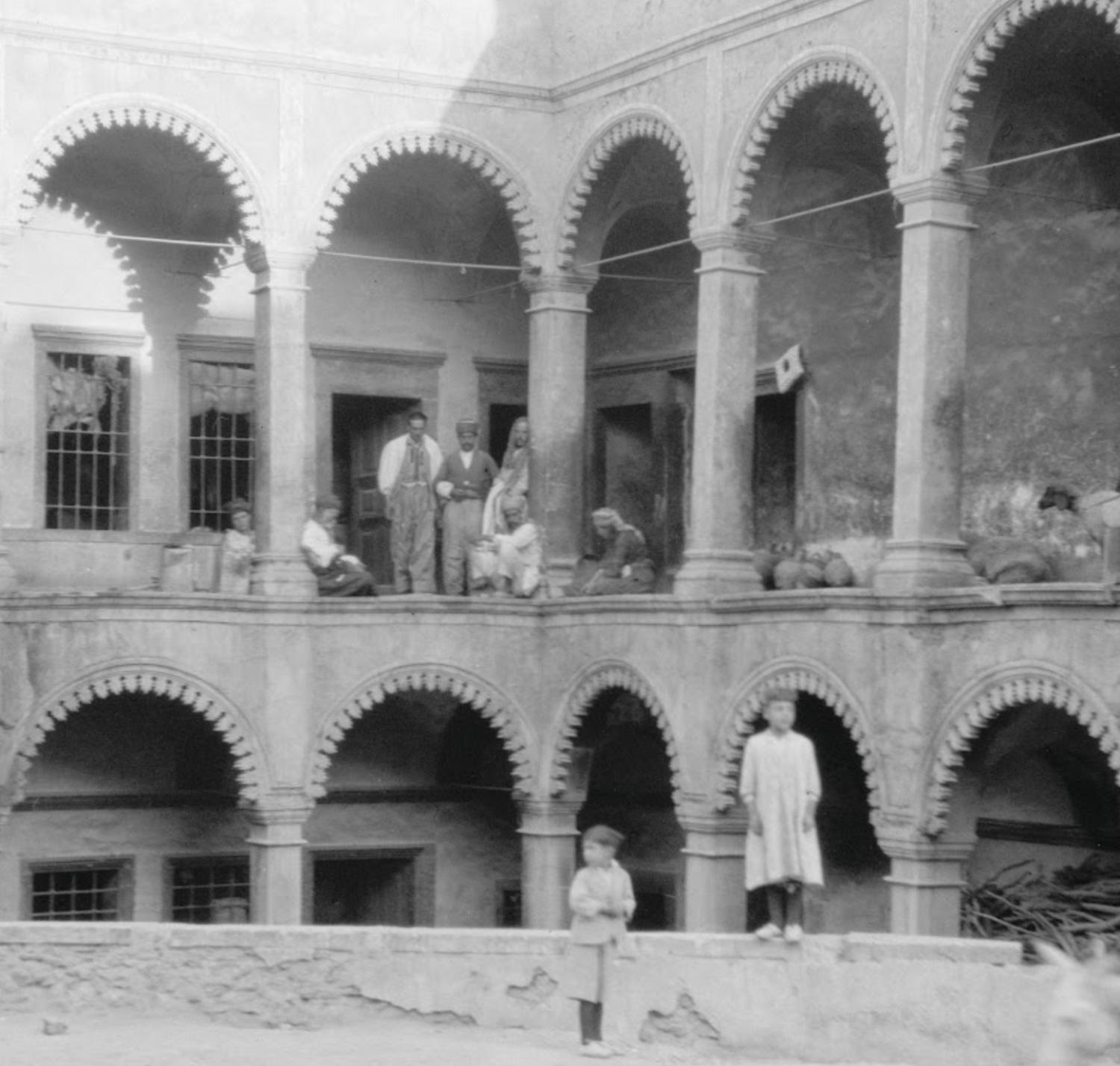

Hartmann’s views were shared by another prominent German traveler, Oskar Mann (1867-1917), a linguist trained in Iranian languages as well as Arabic, Aramaic, and others. Elevated to the title of professor in 1904 by order of Kaiser Wilhelm II, Mann traveled through the region in 1901-1903 and 1906-1907, visiting Mosul and Baghdad before continuing into Persia.

Like Hartmann, Mann believed that the Kurds had great cultural potential. In his travel accounts in Persia, in connection with his linguistic research, he was definitive in countering prevailing stereotypes: “The Kurds, who are reviled by all other nations as incurably stupid, are infinitely more intelligent than all the fellows who make fun of them put together. Where in the whole of the Orient can one find such a wealth of folk poetry as among the Kurds? And every Kurdish farmer will tell you stories and tales off the top of his head.”

Both Mann and Hartmann also commented on Ibrahim Pasha (1843-1908/09), the famous leader of the Milli Kurds and subject of many travelogues. Their discussions addressed the meaning and purpose of the Kurdish Hamidiye regiments, created by Sultan Abdul Hamid II and commanded by Ibrahim Pasha. In contrast to another well-known German traveler, Max von Oppenheim, both men viewed the Hamidiye critically.

Hartmann considered the Ottoman attempts to discipline parts of the Kurdish population and to integrate them into the Hamidiye regiments and into the imperial military structure to be harmful and problematic. Accordingly, he characterised Ibrahim Pasha and the Milli Kurds as a largely unruly group whose predatory actions, especially toward the Armenians, were, in his view, only thinly concealed by outward signs of military discipline and uniformed presentation.

Imperial visions and the Kurdish future

Yet Hartmann never abandoned the idea that the Kurds possessed great civilizational potential. He subtly hinted at the possibility of Kurdish nation-state formation, though they first had to be made sitting (decent, i.e., civilized under the guidance of a stronger imperial power).

Thus, Hartmann never advocated for Kurdish independence, but rather their incorporation into their own state or into a post-Ottoman federation in a political order ultimately directed by the European Kulturstaaten, above all Germany. Such dreams ended abruptly in 1918.

Military historian at the Centre for Military History and Social Sciences of the German Armed Forces from 2001 to 2024 and lectured at the University of Potsdam.