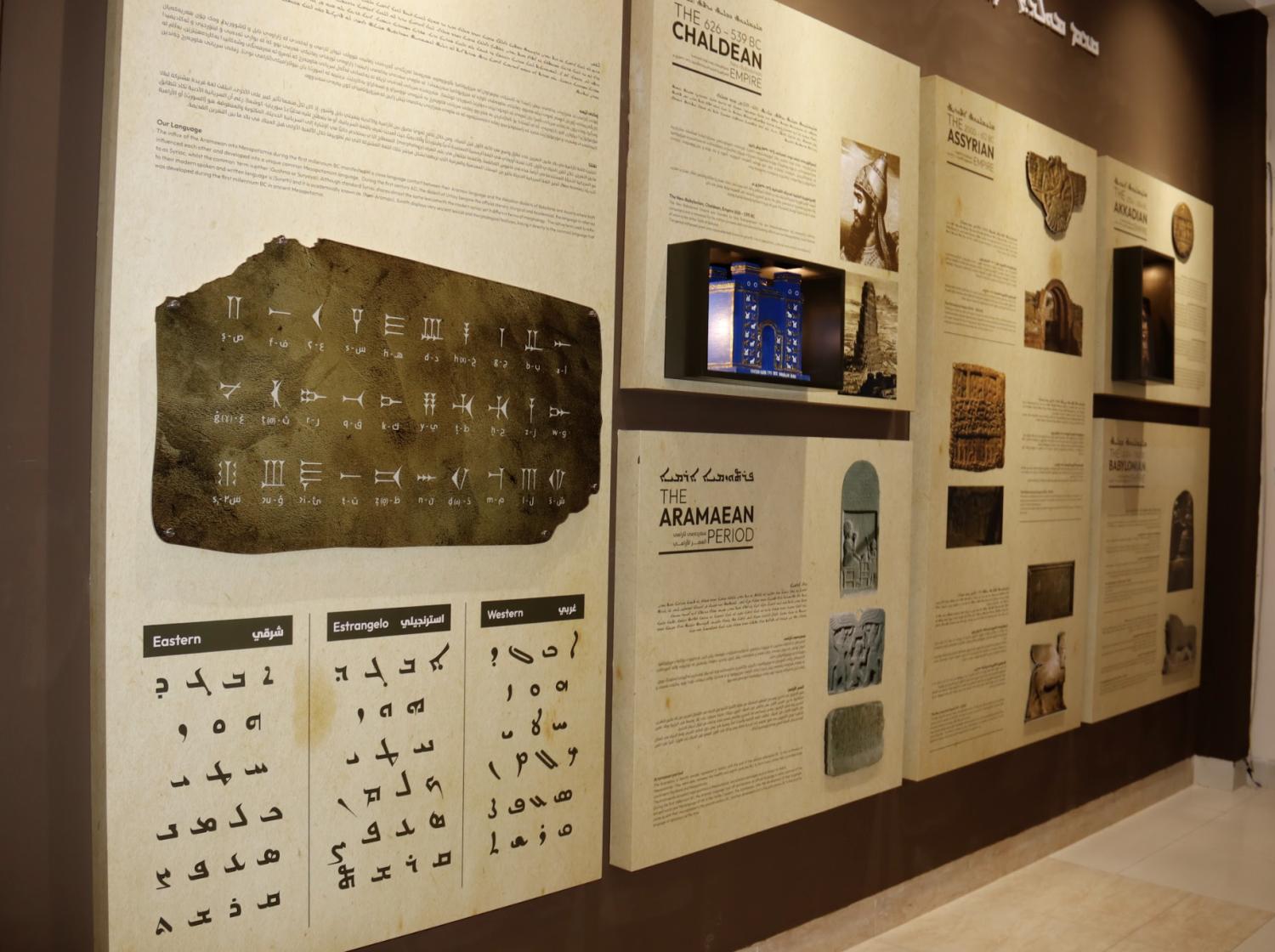

On a quiet morning in Ankawa, a child recites a verse in Syriac, a language with roots deep in the history of the region. Unfamiliar to many, Syriac flows with the memory of centuries and carries the cultural DNA of the community. This is not simply a classroom exercise, but an act of preservation, a revival of identity.

Since 1992, when the Kurdistan Region launched its mother-tongue education program, the Syriac language has undergone a remarkable transformation. What began modestly has grown into a significant movement to safeguard the linguistic and cultural heritage of the Christian community.

The most visible achievement of this revival is in schools. Official data from the Syriac Education Directorate of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Ministry of Education reveals that 7,650 students are currently enrolled in 33 schools across the region where Syriac is the language of instruction. Beyond classrooms, Syriac remains a living tongue for more than 200,000 Christians who continue to speak it as their mother tongue.

The growing base of learners reflects more than statistics; it is a generational bridge. For decades, Syriac risked becoming a language confined to church walls, whispered prayers, or fragments of lullabies. Today, through structured curricula, it has reclaimed a space in daily life.

The role of institutions

Supporting this effort is an entire cultural infrastructure. The General Directorate of Syriac Culture and Arts has taken center stage, creating a specialized body that not only protects the language, but also celebrates it – in schools, in culture, and in museums.

Caldo Ramzi Oghna, Director General of Syriac Culture and Arts, speaks passionately about the directorate’s mission: “Our role in nurturing the mother tongue lies in numerous activities and initiatives.”

These range from hosting festivals on International Mother Language Day – observed on February 21 – to creating projects aimed at exposing the language to children, such as folk songs turned into animated films to make learning Syriac fun and accessible.

The directorate also hosted its first major symposium, under the patronage of KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani. The event brought together 54 scholars from universities across the world, including Harvard and Oxford, alongside 200 academics specializing in Syriac studies. Oghna describes it as the largest Syriac-focused scholarly gathering ever held in the Middle East.

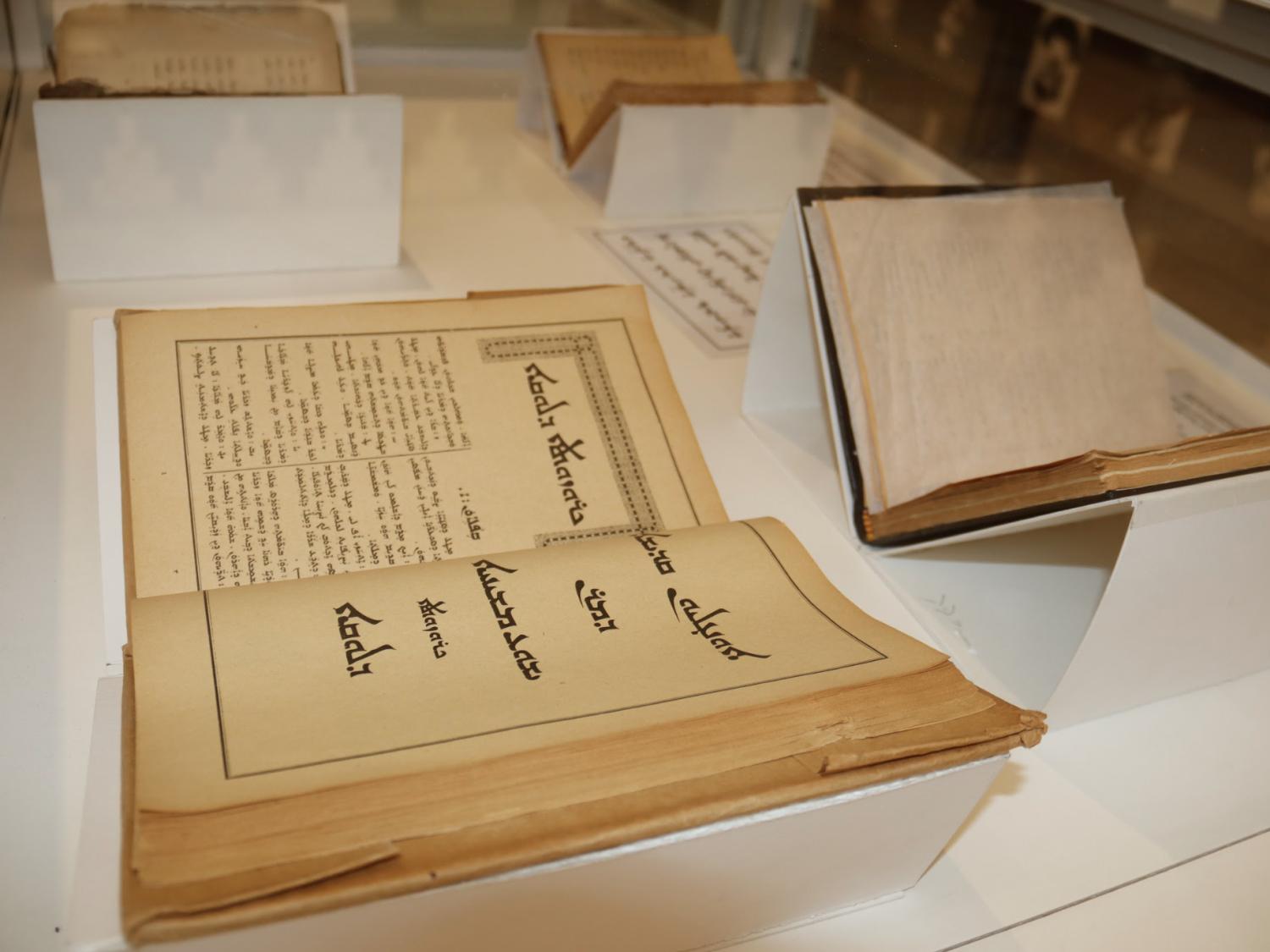

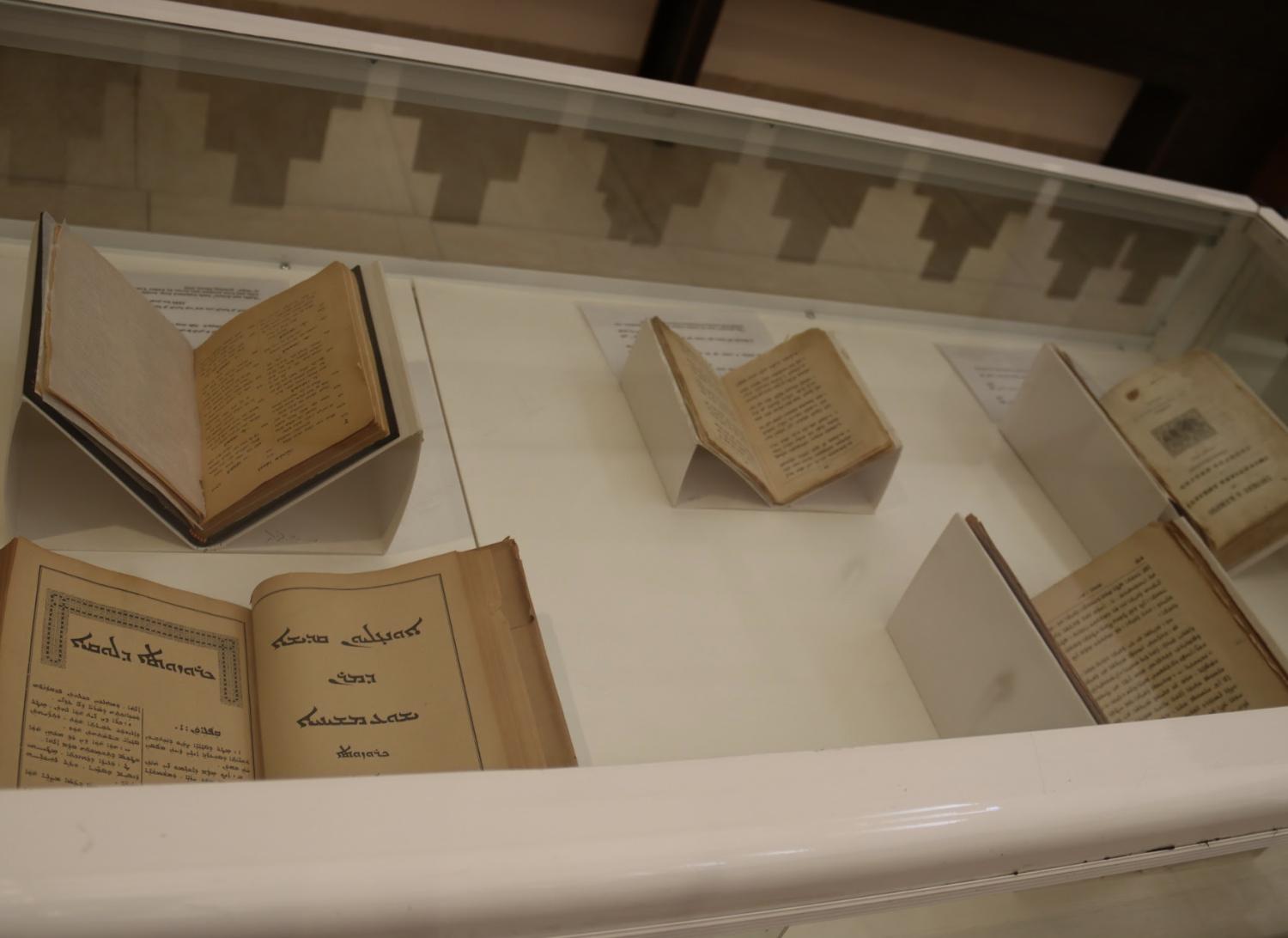

The Syriac directorate has not confined itself to academia. Every year, it organizes the Syriac Heritage Festival, a community celebration where handmade crafts and traditional arts come to life. There are also efforts to publish children’s booklets for language learning, ensuring that even the youngest members of the community grow up familiar with their ancestral language.

Publications and media outlets serve as another vital channel. The quarterly cultural magazine Banipal publishes articles and poetry in four languages – Syriac, Kurdish, Arabic, and English – reflecting both diversity and inclusivity. A dedicated website, Facebook pages for the museum and library, and other social media accounts amplify the reach of their activities.

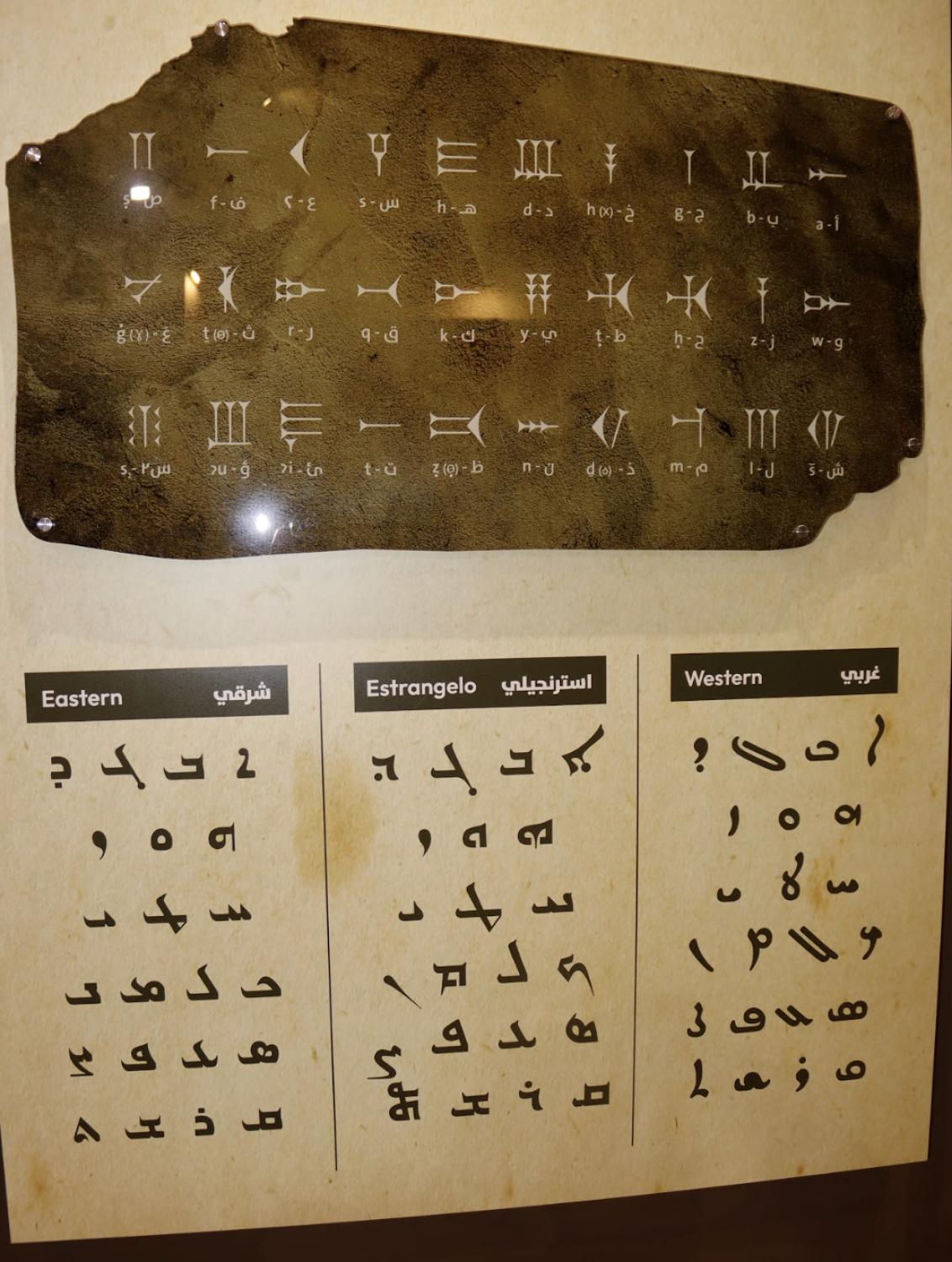

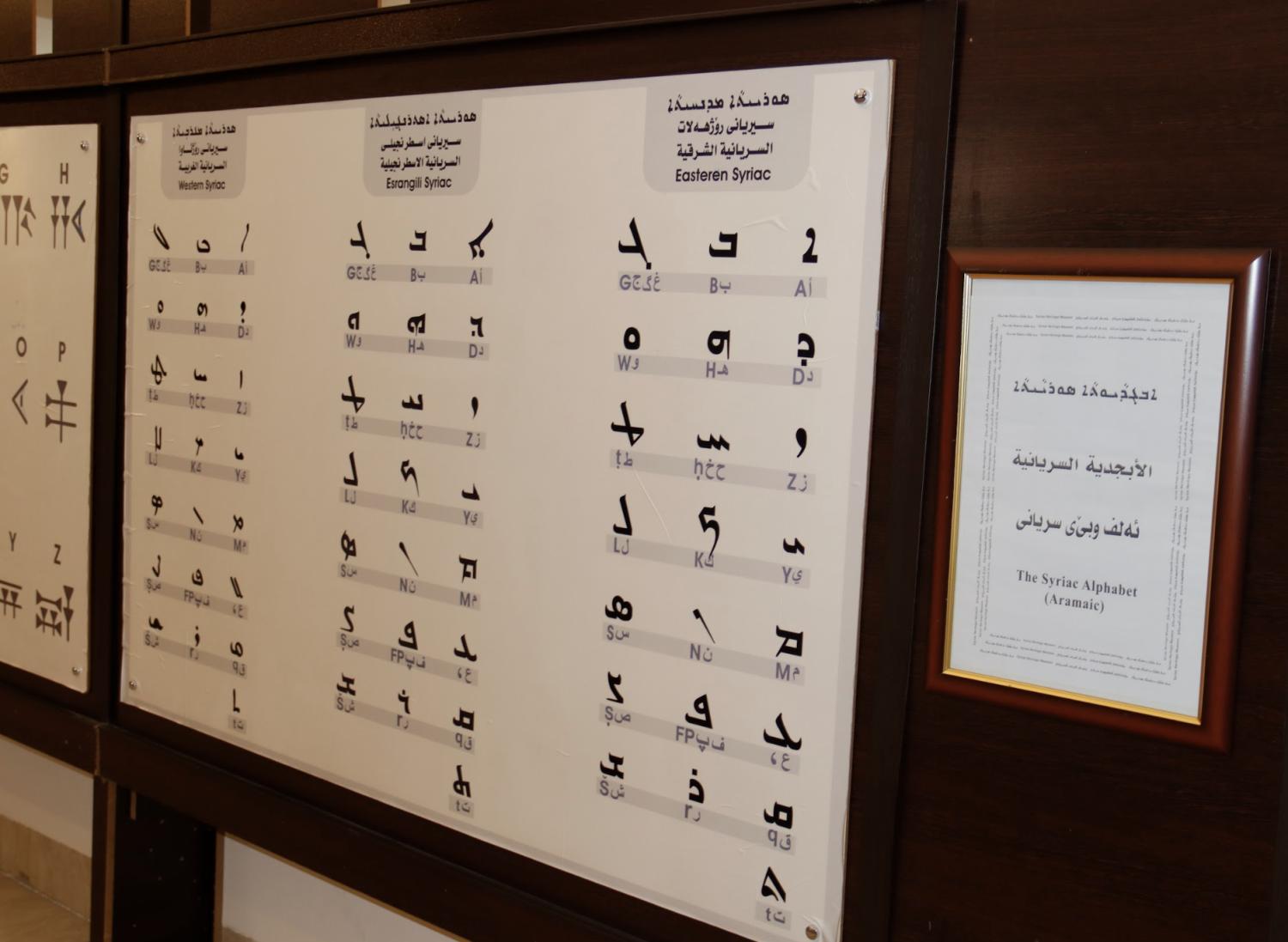

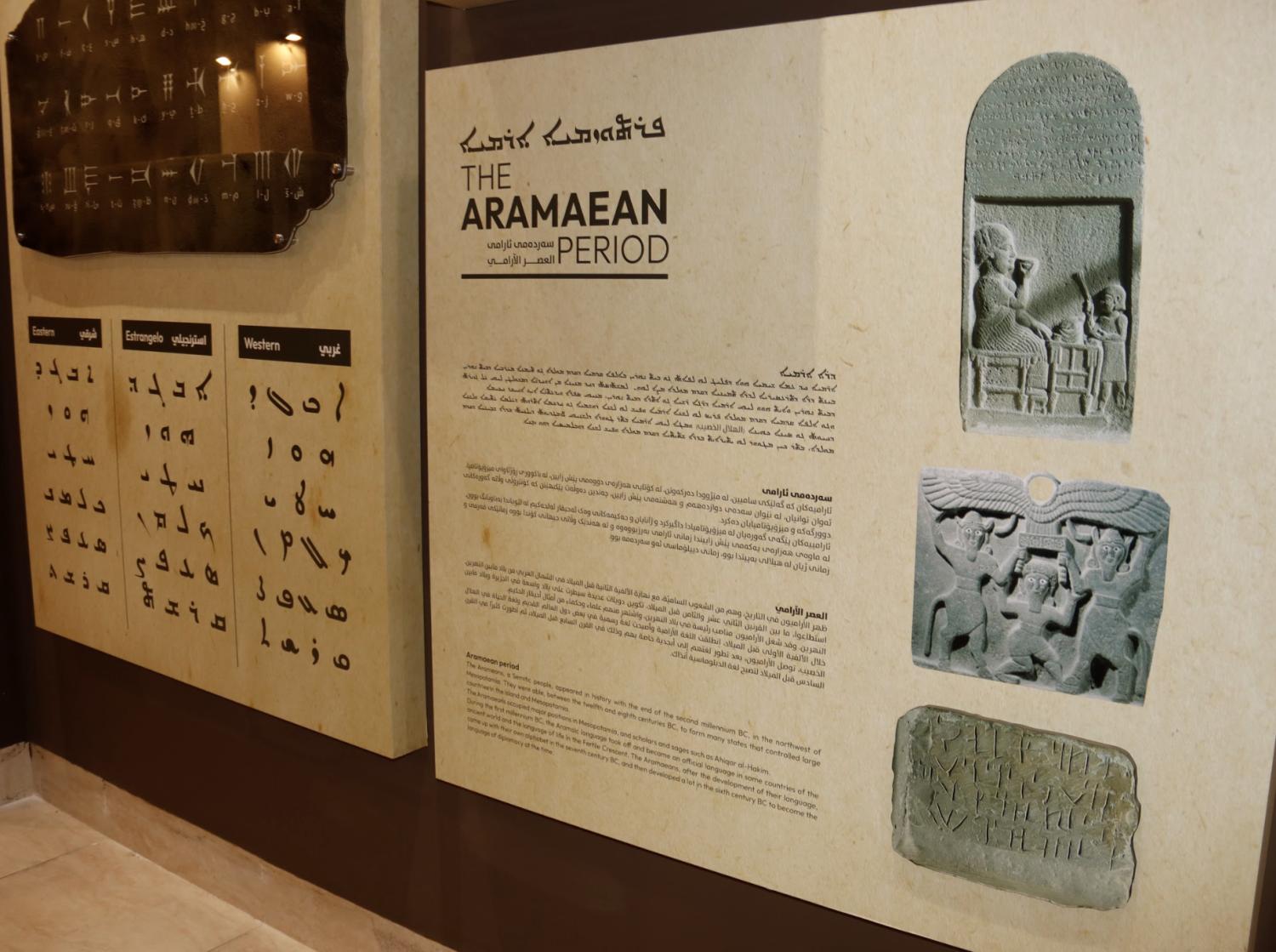

The Syriac Heritage Museum

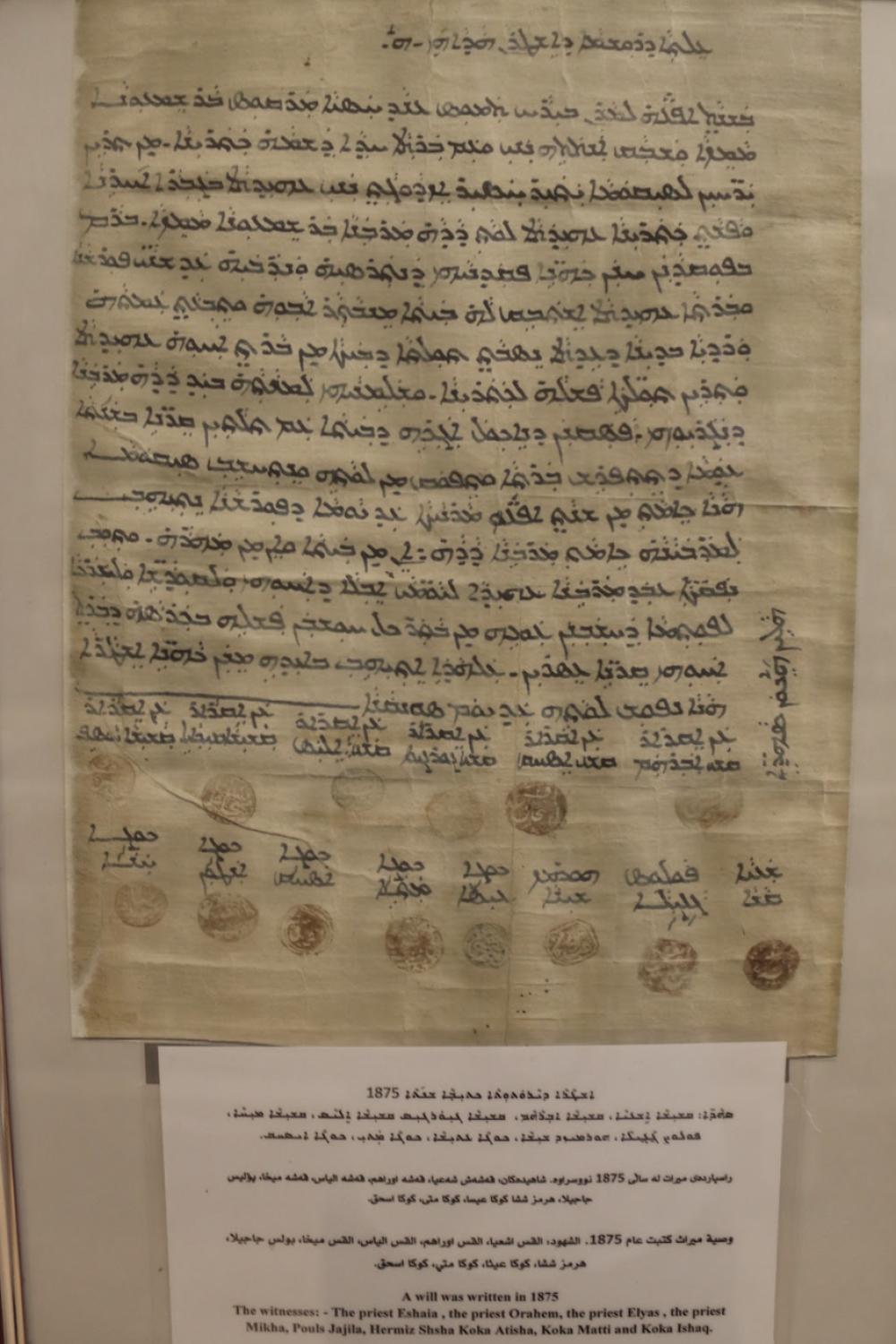

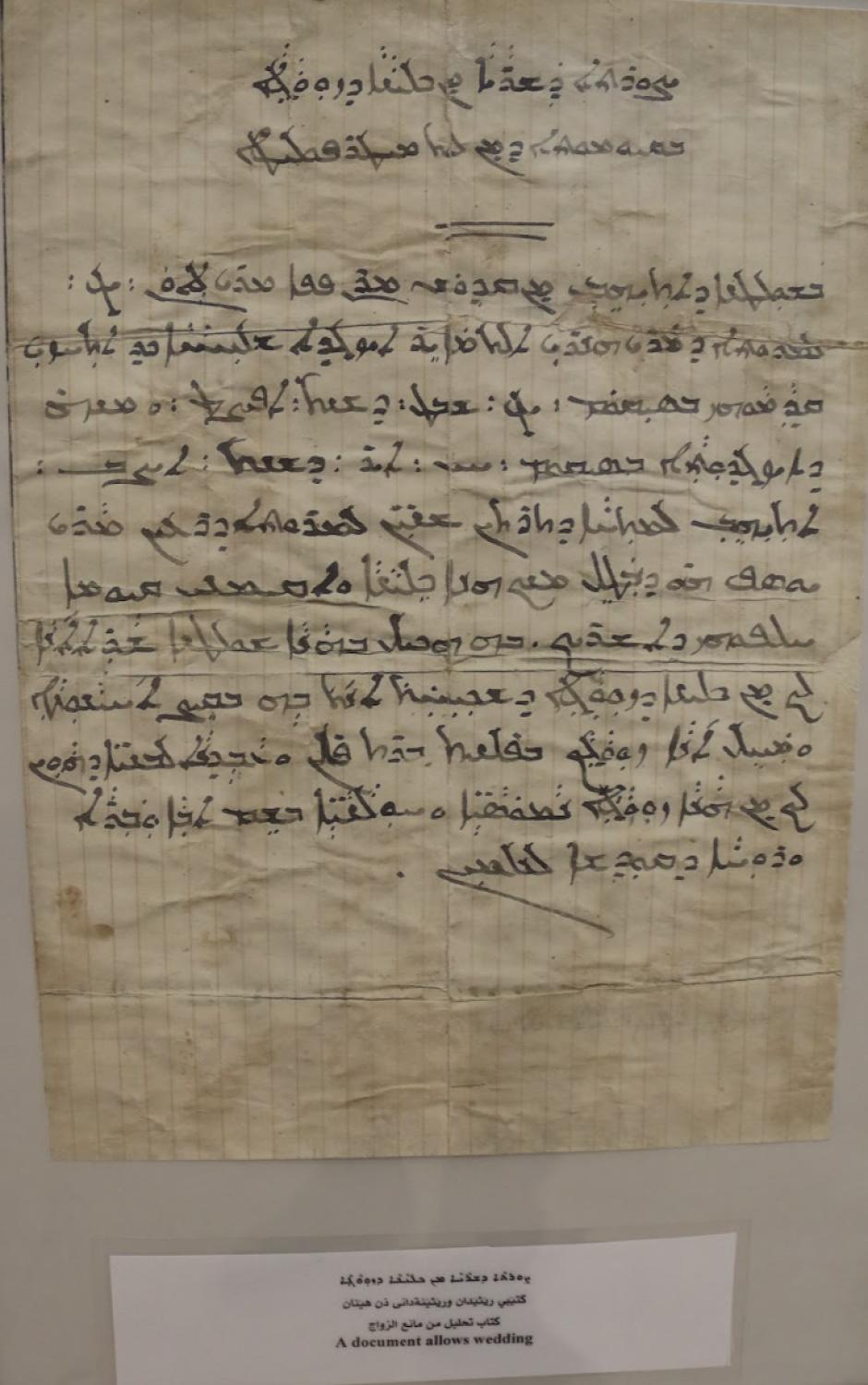

Oghna describes the Syriac Heritage Museum in Ankawa as the “ambassador” of the directorate. Within its walls, visitors encounter artifacts and artworks that narrate centuries of history not just of the Syriac people, but of all the communities living alongside them.

“The museum is a reminder of our rich heritage, one that distinguishes us yet unites us with others, as it remains an inseparable part of Kurdistan’s culture,” says Oghna.

The institution’s role is not confined to Ankawa. With branches in Duhok and active programs across the Nineveh Plains, its influence stretches beyond the Kurdistan Region. In recent years, Syriac cultural activities have crossed borders, extending to Lebanon and Syria’s Qamishli and engaging diaspora communities in Russia, Armenia, and Iran. In Lebanon, for example, the directorate organized its first Syriac festival for expatriates, connecting scattered generations to their roots.

For Oghna, the mission is not only about heritage but also about strengthening the social fabric. He highlights how diversity is central to building a cohesive society: “When a community is united and diverse at the same time, differences become a source of strength, not division.”

This philosophy has guided initiatives like the Open Book Forum, whose third edition carried the theme of “Diversity.” One notable project in collaboration with the Ministries of Culture and Education invites Kurdish, Arabic, and Turkmen schools to visit the Syriac Heritage Museum. The idea is simple yet powerful: when students witness another community’s heritage firsthand, the bonds of unity strengthen.

Looking ahead, Oghna outlines ambitious plans for festivals and cultural activities in villages across Erbil and Duhok, from a heritage festival in Armota in the Koy Sanjaq District to a second Syriac theater festival.

Art for cultural preservation

Reviving Syriac is not confined to classrooms or museums – it is also performed on stage. Rafiq Hanna, a theater and television director from Ankawa, views the mother tongue as inseparable from identity. He believes art, particularly drama, is essential for both cultural preservation and peaceful coexistence.

“The role of drama cannot stand alone without media, music, visual arts, and Syriac-language press,” Hanna explains, adding that their “culture is not a closed project – it is a message of peace and coexistence.”

Theater productions, sometimes bilingual, serve as bridges between communities. They retell stories of historical coexistence in moving, human terms, reminding audiences that art binds people in ways politics cannot.

For Ator Andrious, a journalist from Duhok, Syriac’s importance extends far beyond communication. “It is part of our cultural, historical, and identity heritage,” she emphasizes.

Preserving it means speaking it daily, teaching it in schools, supporting media in Syriac, and celebrating it through poetry, song, and traditional theater. She echoes a phrase now embraced by many in the community: “Our language is our existence.”

Yet challenges persist. Private schools often prioritize English-language curricula, overshadowing Syriac – a trend increasingly common across schools. Younger generations, immersed in technology and globalized culture, show growing preference for English, leaving Syriac vulnerable to neglect. The risk is real: if it is not supported, this ancient language could once again retreat into obscurity.

The burden of survival

Despite fears, the ongoing work of activists, cultural leaders, and educators has breathed resilience into the Syriac language. The directorate’s festivals, publications, museums, and children’s programs represent more than cultural activities; they are a collective shield against erasure.

The Syriac story in Kurdistan is the story of survival. It is about a people who refuse to let their words be silenced, who understand that a language is not only a tool for communication, but also the essence of identity. As voices young and old continue to echo in Syriac across classrooms, theaters, and festivals, the message resounds clearly: an ancient language is still alive – and will not vanish.

is a journalist based in Erbil.