“Mulla Mustafa is in Tehran!”

This message arrived at our newspaper’s news desk from Shapour Dolatshahi, a diplomat friend who headed the protocol desk at Iran’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Needless to say, this was big news, and we saw it could become bigger if we managed to publish this scoop.

The question was how to find the great Kurdish leader’s location, as it seemed that “the authorities” did not want the news to come out.

The official news agencies – typically quick to report the arrival of even the most obscure foreign figures – remained silent. The Foreign Ministry’s press spokesperson Mahmud Salehi claimed that he knew nothing about it.

It turned out that Dolatshahi – who had for years informed our newspaper of comings and goings of foreign dignitaries – had talked out of turn this time. When we asked where we could contact the Kurdish leader, he backpedaled, claiming he had merely passed along some “rumors.”

As a last resort, we turned to Colonel Issa Pejman, an army intelligence officer who had acted for years as liaison with Kurdish politicians in Iraq. He helped our reporter Jalal Hashemi locate the villa where General Mustafa Barzani had been housed as a distinguished guest. One phone call later, and we had an invitation from Barzani for tea and – we hoped – sympathy.

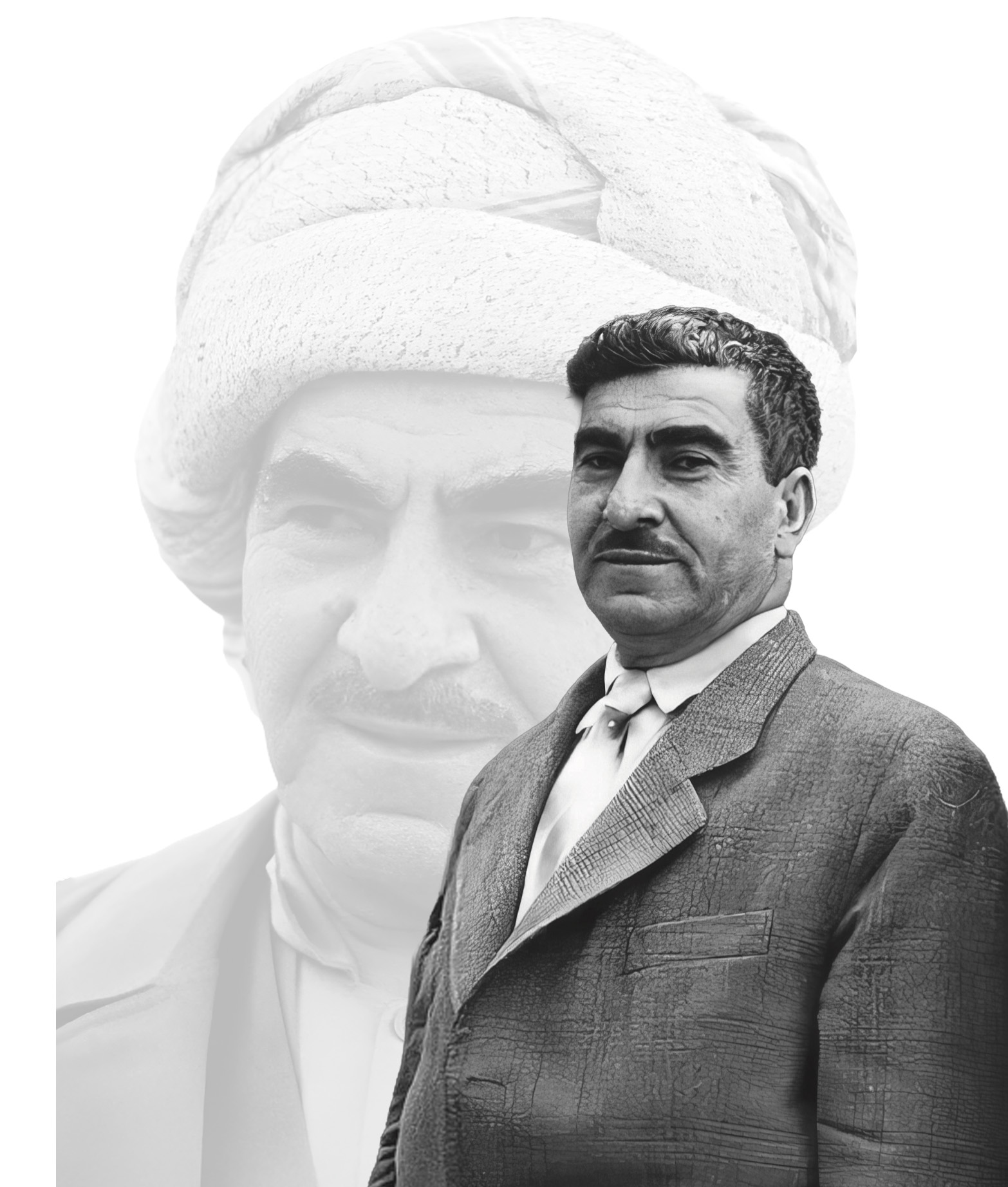

Barzani knew Kayhan had long supported the Iraqi Kurds’ struggle for freedom, justice, and dignity. To many of our readers – indeed to many Iranians – Mullah Mustafa, as he was endearingly called, was something of a hero fighting for our Kurdish “kith-and-kin” in neighboring Iraq.

Tete-a-tete with General Barzani

For a couple reasons, I decided, as Kayhan’s editor-in-chief, to do the interview myself.

First, I thought that if the authorities did not wish to allow General Barzani to transmit a message to the outside world, they would find it easier to browbeat a reporter rather than the editor. I must also admit that I was personally curious to assess the general’s mood in a face-to-face encounter.

I decided not to use a tape-recorder to avoid ending up with what might sound like a scripted dialogue. This would give him a chance to deny anything he might have said that might rankle “the authorities” by claiming he had been misquoted.

Let me also admit now – half a century later – that subconsciously perhaps I wanted General Barzani to be portrayed as a key leader in a just war, not as a defeated general retreating from the field of a lost battle. Ethically, it may not have been the best choice; a reporter is supposed to keep personal views out of their work.

Nevertheless, there are times when maintaining the myth of journalistic impartiality becomes hard, if not impossible, to swallow.

The choice was between Saddam Hussein, who regarded politics as a mixture of brutality and betrayal, and General Barzani, who had gone the extra mile to find a formula for coexistence with Baghdad but who had been betrayed by his U.S. allies and abandoned by his Iranian kith-and-kin.

We met in the large salon of the sumptuous villa where he had been housed by the Iranian Imperial Court. The massive Persian carpet and oversized chandelier gave the room the air of a neglected ballroom.

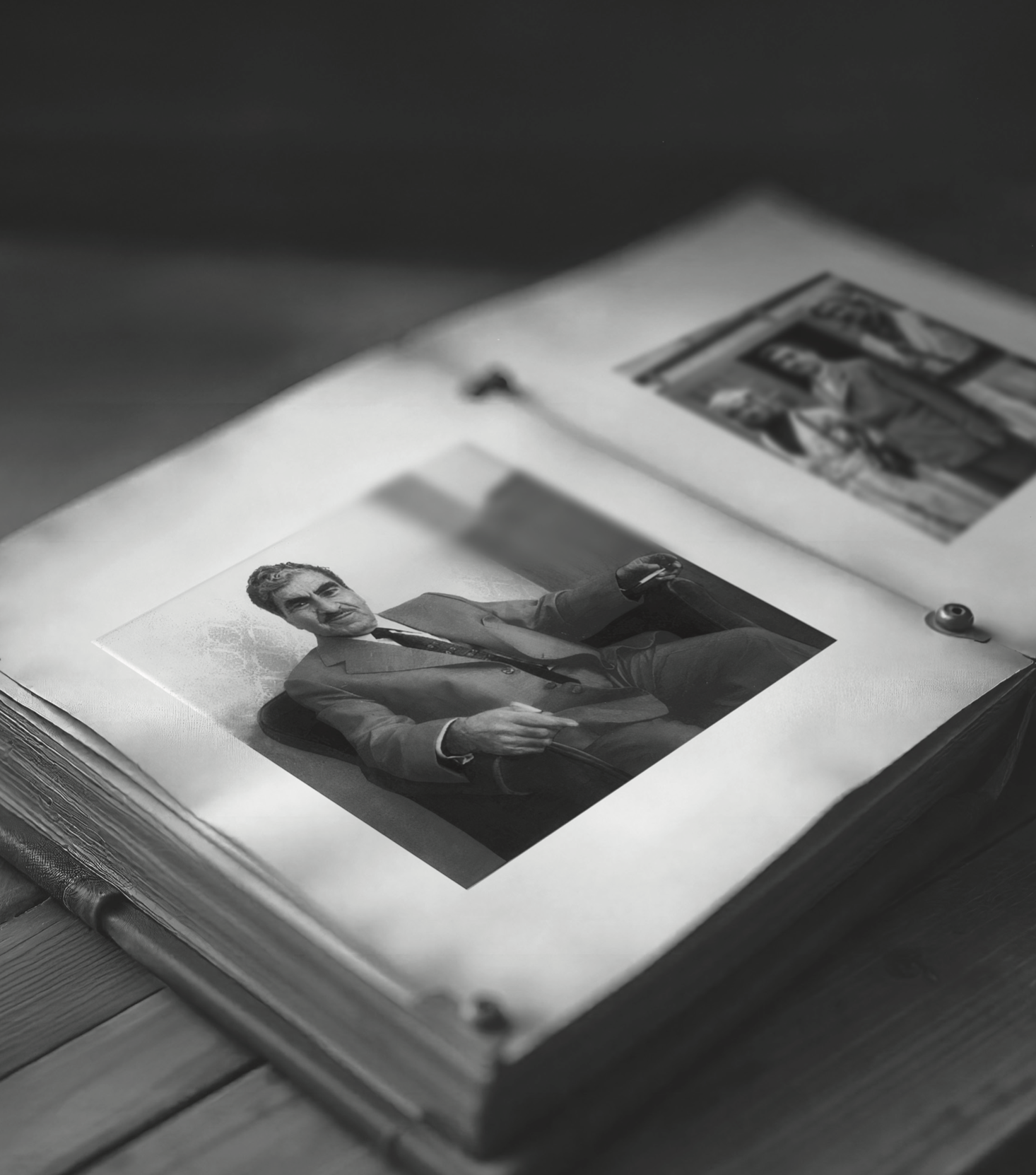

General Barzani was sitting in one corner with an oblong tea table laden with fruit, chocolate, and cookies in front of him. By the side of the table there was a pile of books and the general’s wood-carving knives. A veritable artist, he was always carving something – a pipe, a wooden bird, a picture frame. Iran’s then-Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveyda owned one of Barzani’s pipes and on occasions showed it to visiting foreign leaders as a “peace pipe.”

On that day, however, he had no wood to carve. Instead, he started peeling a huge orange, turning the skin into a winding cobra.

Beaten but sanguine

The big shock was to see General Barzani in a somber grey European suit that seemed somehow to diminish him, especially to those who had always seen or imagined him in his fine majestic Kurdish costumes.

In that ill-fitting suit, he looked like a forlorn hawk trapped in a cage.

Soon, however, the good mullah started to strike out of the cage, first by rattling the bars and then breaking out. The suit remained but was superseded by the trompe-l’oeil image of a Kurdish costume, complete with the bandolier of a mountain fighter.

His core message was clear: he was neither broken nor defeated. His work in the struggle for freedom, justice, and dignity for his people was completed, but the war would go on, albeit in different and novel ways, and on battlefields that the future would shape.

He never mentioned the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and his Ba’athist cohorts by name. However, it was clear to whom he was referring when he recited Surah At-Takathur from the Quran. This surah contains a warning to the evil people in this world, stating that they will greatly regret their actions with the advent of the Day of Judgement.

General Barzani seemed to have boundless faith in the younger generation of Kurds to continue the struggle for freedom and dignity.

He said he could not recommend any particular form for the fight for freedom but was sure that the younger generation would invent its own methods.

At the time I did not know how to interpret his cryptic message.

Now, however, I think he meant to tell the Kurds to despise their foes strategically, but to take them seriously tactically and to count on friends tactically but not depend on them strategically.

During the interview, he indirectly managed to pass on three important messages.

First, Iraq will not achieve genuine and lasting peace without understanding and acknowledging its existential reality as a multi-ethnic nation.

Second, the United States was wrong in thinking that by sacrificing the Kurds it had checked Baghdad’s inevitable siding with the Soviet Bloc.

Finally, Tehran had made an error by helping Saddam Hussein get off the hook in the hope that his wild-eyed, fake pan-Arabism would never be a threat to Iran.

A delicate diplomatic dance

At the start of the interview, General Barzani had made a gesture toward one of two men present in the salon, meaning he would rather have him out of the room.

I approached the man and informed him that “the honored guest” seemed to prefer to talk to me alone. He agreed and left the salon.

After the interview, the man presented himself as Ali Ahsani, head of the public relations’ office of SAVAK, the Iranian security agency. He turned out to be a polished gentleman who had instructions to chaperon the Kurdish leader while in Tehran but not impose anything on him.

The second man was Masoud Barzani, the general’s son. Throughout the interview, he stood up with his back to a wall and said nothing. As a good son according to Kurdish tradition, he could not sit or speak without being allowed to do so by his father. At the time, no one knew when and how the young Masoud would become a major figure in the Iraqi-Kurdish saga.

Having secured the interview, I realized that though there may not have been a clear order about not giving General Barzani a platform, the government might not like to have him say his piece – which would, as it turned out, be taken up by news agencies and broadcast throughout the world.

Then-Foreign Minister Abbas-Ali Khalatbari had spent more than two years negotiating a deal with Baghdad to recognize Iran’s position on the Shatt al-Arab border estuary, with the implicit hope that the two neighbors would refrain from hostile acts against each other.

More importantly, the Shah himself had only recently given Saddam Hussein a diplomatic victory at the OPEC summit in Algiers in 1975, where the treaty that Khalatbari had negotiated was unveiled.

Also, at the time of General Barzani’s interview, Tehran was preparing for an official visit by Saddam Hussein at the invitation of Prime Minister Hoveyda.

My fears were confirmed when Ghulam-Reza Tajbakhsh, then-Deputy Foreign Minister for Political Affairs, called to say that the ministry had heard about attempts at publishing a statement by General Barzani and that he wanted to warn us against doing so.

The solution I found was to publish a short version of the interview first in the morning daily Rastakhiz, the official organ of the ruling party just founded by the Shah. This was easy enough, as Kayhan printed Rastakhiz, and its director Mehdi Semsar was a former editor of our daily.

The interview, published with a page-one banner headline in Rastakhiz, persuaded all those who might have wanted to keep Barzani silent that the interview must have received the green-light from the authorities. With such a shield we could publish the full text in Kayhan itself, which appeared in the afternoon.

It became one of our biggest scoops and pushed our circulation up by 10% that day. (This may sound inelegant to you, but an editor is always anxious to increase circulation!)

Having done scores of interviews with grandees from across the globe, I never thought that General Mustafa Barzani would get such attention.

The task that history assigned him

In the decades since, I have often been asked about the circumstances under which that interview took place.

Some have queried me about the headline used by Rastakhiz: “My task is complete!” That title is open to misinterpretation, especially by General Barzani’s political foes, who often masqueraded as friends.

He did not mean that he had achieved his goals. What he meant that he had completed the task that history had assigned him in an epic struggle – and that the next generations would have the task of continuing it.

Why such interest in an event that should have faded into the historical background?

Is it because it turned out to be his last public statement, as he was soon struck by cancer and was to pass away in far-away United States?

Maybe.

But I think the abiding interest is prompted by the general’s heroic fight for his people’s freedom, justice, and dignity.

In the interview General Mustafa Barzani, in effect, said he was not going away for good.

“I will be back,” he promised.

He kept his promise, as his body was flown from the United States to Iran to be buried in Oshnavyeh, and then eventually in his native village in the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

It was not only his mortal remains that returned home. So did his aspirations.

Amir Taheri is an esteemed Iranian journalist who contributes weekly articles to various renowned international newspapers. He served as the executive editor of the daily newspaper Kayhan in Iran from 1972 to 1979. In March 1975, Taheri conducted a notable interview with the late leader General Mustafa Barzani, who sought refuge in Tehran following the ill-fated Algiers Agreement between Iraq and Iran, a development detrimental to the Kurdish liberation movement in Iraqi Kurdistan