At the dawn of the 20th century, the Kurds and Armenians were largely forgotten about as the right to self-determination – a principle defended in the 1910s by then U.S. President Thomas Woodrow Wilson – was granted to various peoples around the world. As a result, two genocides claimed hundreds of thousands of victims in these two communities.

A man from Sulaymaniyah had warned the countries responsible for negotiating the peace treaty after World War I of this eventuality. This man was Mohammed Chérif Pasha Babanî, the head of the delegation in charge of representing the demands of the Kurdish nation. One of his delegation’s key aims was the creation of a greater Kurdistan integrating the vilayets of Bitlis and Van with access to the Mediterranean Sea at the Gulf of Alexandretta to enable “the flow of its oil and its other mineral and forest wealth.”

This former general of the Ottoman army had been ostracized from Turkish diplomacy for denouncing the Armenian genocide in 1915, as well as because this Francophile trained at Saint-Cyr – the largest military school in France – had disapproved of the alliance with Germany. From the point of view of the victors of the First World War, this should have been enough to give credit to the former ambassador of the Sublime Porte in Sweden. Instead, those who would decide the fate of the Middle East ignored his warnings.

In retrospect, it is clear that Chérif Pasha was right to be worried. On March 1, 1920, in a memorandum addressed to the President of the Supreme Council of the Peace Conference, he explained why “the distribution of the wealth of the soil in the Kurdish countries cannot in any way serve as a pretext for the separation of Kurdistan into several zones of influence, nor to its division.”

Considering the forces present, with “warlike populations jealous of their national independence,” he anticipated the consequences of a division of Kurdistan in these terms: “Disorder will reign in an endemic state, unless the Allies want to maintain there in perpetuity a strong army which will itself be exposed to all the attacks of a guerrilla war.” The United States was able to verify this at its own expense, decades later. On the ground, however, it is the Kurds who have paid the highest price.

Legalizing discrimination

Indeed, what could be easier for the region’s states than to attack a people whose existence was denied by the signatories of the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923? Less than eight months later, the Kurds of Turkey were the first to see the ax fall, despite promises from Mustafa Kemal of Turkish-Kurdish friendship. On March 3, 1924, the very day the Caliphate was abolished, Mustafa Kemal signed a decree banning all Kurdish schools and associations, as well as any publications in the Kurdish language. From the outset, non-Turkish-speaking citizens were seen as potential enemies of the nation, justifying all discrimination against them.

That same year, a law outlining Iraqi nationality also had a detrimental effect on the fate of the Kurds on the other side of the border. The Failis, a Shiite minority within the mainly Sunni Kurdish community, were the first target.

This law introduced discrimination between the descendants of citizens of the Ottoman Empire and citizens designated as being of Persian origin – in other words, between Sunnis and Shiites. While the former – of the Sunni faith – were considered “authentic” Iraqis and benefited from Iraqi citizenship, the latter had to formalize their request to benefit from citizenship. In this context, the Failis quickly became subject to discrimination, especially along the border with Iran and in Baghdad, where they controlled whole sections of the local economy.

Stigmatized for decades, the Failis became pariahs after the Ba’ath Party came to power in 1968. Like the Jews in Nazi Germany, the Failis were portrayed as an enemy within who were infiltrating the economy for their own benefit.

There was little international reaction, for instance, when 70,000 Faili Kurds were deported to Iran in the late 1960s. Further north, Bashur's Kurds – mostly Sunnis – yearned for more autonomy. They did not realize the hidden intentions of Saddam Hussein, then vice-president of Iraq, who was in charge of negotiations with those he then called “the Kurdish brothers of Kurdistan.”

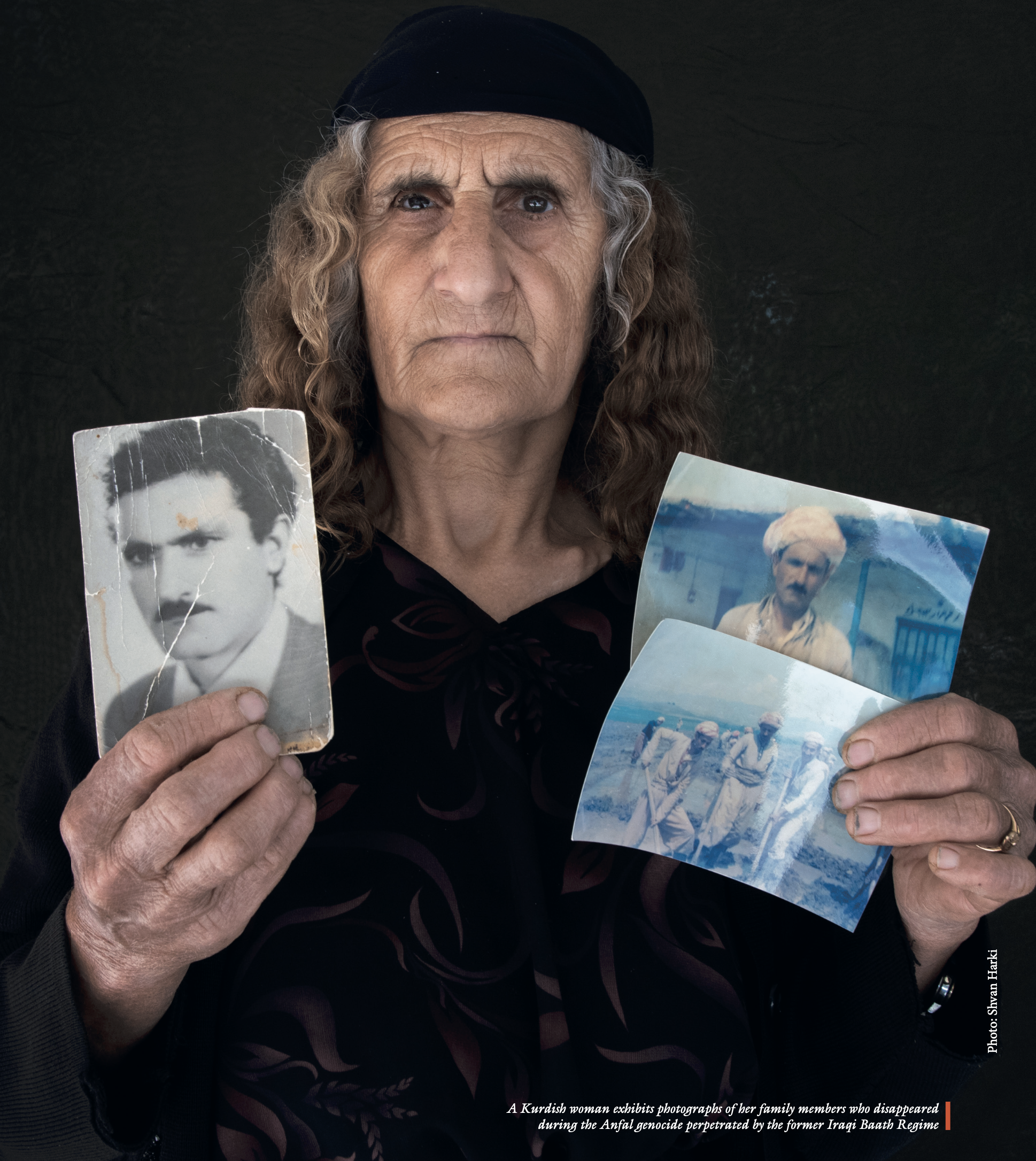

Yet Saddam was already in the first stage of a genocidal policy that steadily escalated in the 1970s and 1980s. In March 1987 he appointed his cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid as secretary general of the north of Iraq to implement the ‘final solution’, which caused 182,000 deaths between February 23 and September 6, 1988.

Divide to exterminate

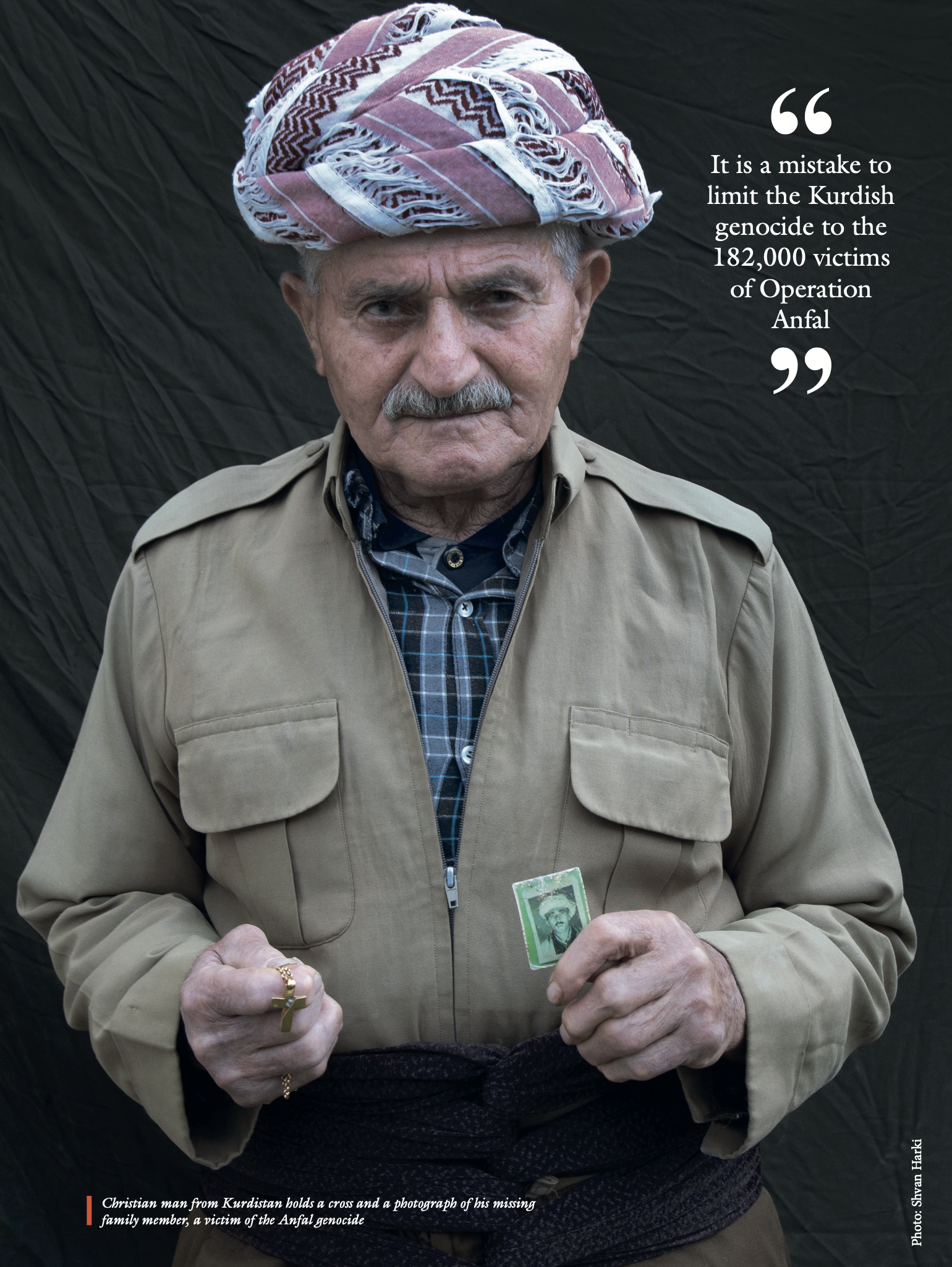

It is a mistake to limit the Kurdish genocide to the 182,000 victims of Operation Anfal. Certainly, for the survivors, it is important to have dates to honor the memory of the victims. However, the proliferation of commemorations in Iraqi Kurdistan is not likely to increase the official recognition of the Kurdish genocide by the international community. Why not? Because it limits the crime to a specific time frame and does not allow the analysis of an overall plan that constituted “the intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.”

The overall plan was not clear at first, as only the Failis were targeted. Divide in order to better exterminate had been the leitmotif of the Ba’ath Party from the start, when it proclaimed “the Arab identity of the Kurdish land” in the early 1970s.

After the Failis, the Sunni Kurds from the Barzan region, Mergasur district, were the next group to experience why genocide includes “the intentional subjection of the group to conditions of existence calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.” Between 200,000 and 300,000 people were deported to camps in southern Iraq in three successive waves in 1975, 1978 and 1982.

But the plan included further “serious bodily or mental harm” that constitutes genocide. For the Faili Kurds, everything accelerated after the adoption of a new decree on May 26, 1980, which made it possible to strip an additional 450,000 Failis of their nationality. Sami al-Fayli estimates that nearly 23,000 Shiite Kurds went missing in the years that followed.

Then the Baathist regime once again focused on the people of Barzan. Far from their mountains, the survivors who languished in tents in the Iraqi desert were repatriated to concentration camps closer to Erbil. For the government, this move aimed to facilitate the arrest of men and boys aged nine and over in the summer of 1983. No one in the international community has ever heard of the Barzan 8,000. And yet, the parallel is glaring with the recognition of the 8,000 Bosnian men and teenagers who perished in Srebrenica following the ethnic cleansing operation perpetrated from 1992 to 1995 in areas controlled by the Army of the Serb Republic of Bosnia.

But the Kurdish genocide did not stop there. Laws, decrees and regulations issued by the Iraqi authorities continued to legitimize the Arabization of the Kurdistan region throughout the 1980s. The climax of this policy was the adoption of decree 4008, on June 20, 1987. Seventeen days before, on June 3, General al-Majid had signed a directive delimiting eight ‘prohibited zones’. In his note n° 28/3650, he specified that “the armed forces must kill any human being or animal present in these zones.”

For the Kurds, these eight “Anfal” have since been commemorated as a genocide. However, this even was just one step in the overall plan, starting in the late 1960s, to divide the Kurds into several sub-groups to eliminate them more easily.

To date, only six countries have partially recognized the Kurdish genocide. The Iraqi Parliament was the first to rule on Anfal on June 24, 2010, followed by Norway and Sweden in 2012, then England and South Korea in 2013. In addition, in 2010, the Federal Supreme Court of Iraq recognized that the Halabja massacre also constituted a genocide. The Iraqi Parliament spoke out on the Faili genocide in 2011. Most recently, on March 2023, the Austrian Parliament recognized the Kurdish genocide committed in Halabja in March 1988.

This form of recognition makes it seem as if each of the horrors committed under the aegis of the Ba’ath Party constituted a genocide in its own right, whereas they constituted stages of a single long-term plan. The Kurdistan Regional Government should promote this understanding of the events on the international stage if it wants the Kurdish genocide to be officially recognized one day. Otherwise, events such as the 2014 killings of Yezidi Kurds at the hands of former Ba'athists who joined ISIS will happen again, whether against Yezidis, Failis, or Sunni Kurds.

Béatrice Dillies, a journalist at Dépêche du Midi since 1995, has dedicated the last decade to uncovering the Kurdish genocide in Iraq. She has interviewed over a hundred survivors from the 1969-1989 genocide era. Her book, "A Forgotten Genocide, the Broken Voice of the Kurdish People," provides essential insights for achieving justice for this remarkable stateless community.