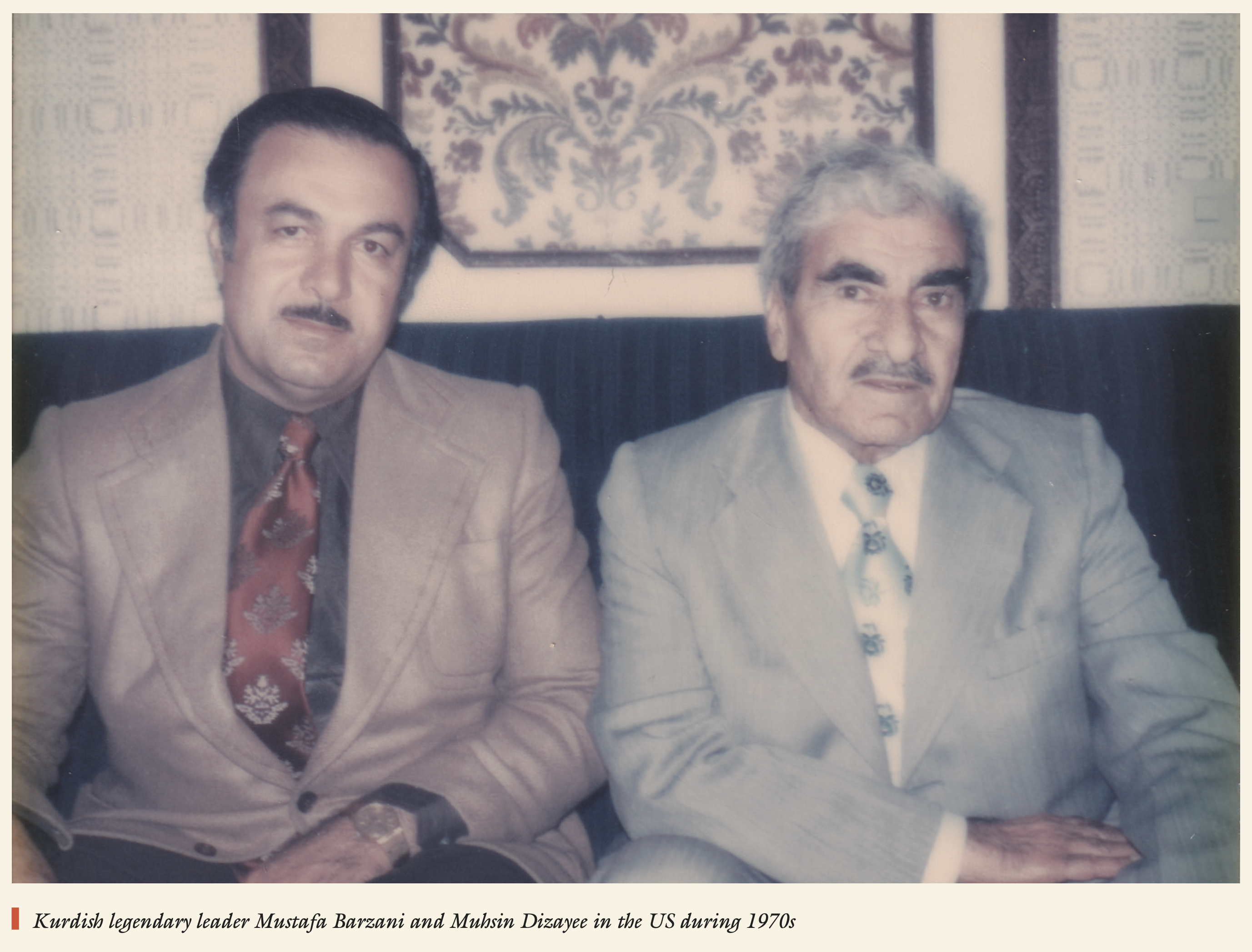

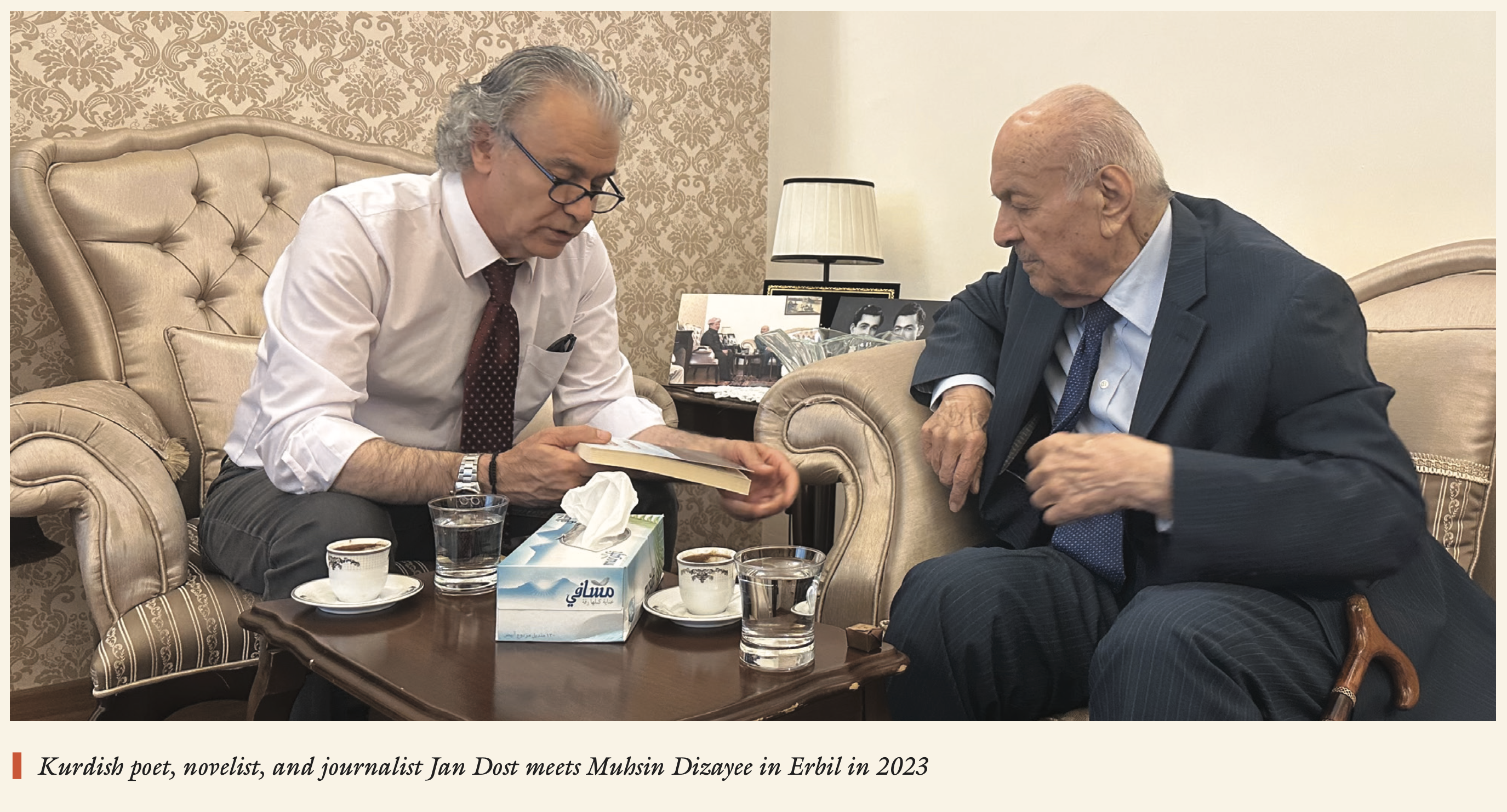

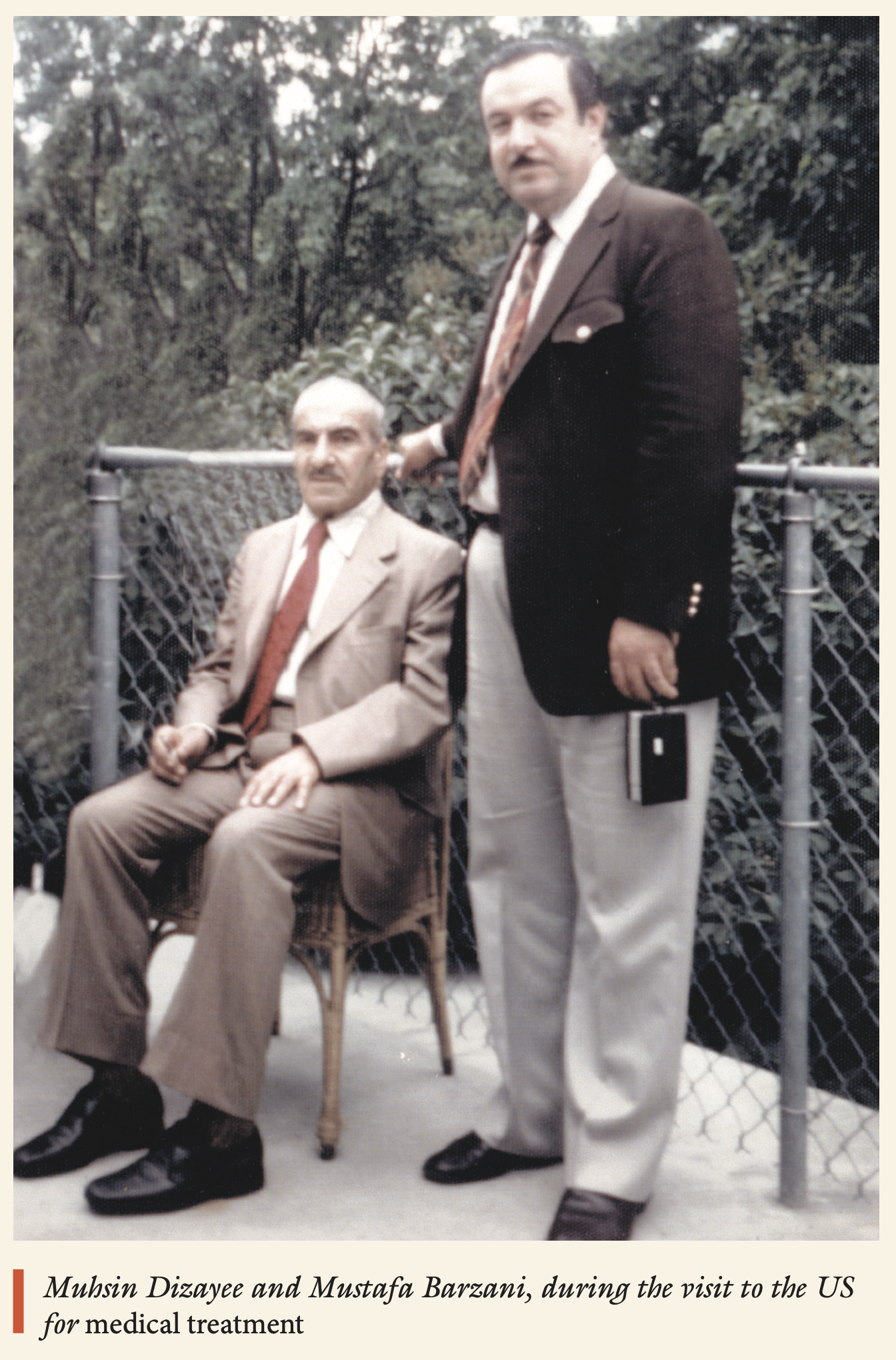

In early May this year, before the heat wave struck Erbil, my journalist friend, Dilbixwin Dara, and I were on our way to the Royal City neighborhood. Our destination was the home of the venerable Kurdish politician, Muhsin Dizayee, who, despite being over 90 years old, still exudes elegance and gentleness. I had met him briefly a few days before at a funeral but had not had the chance to ask him the time he spent in Washington, D.C., with the historic Kurdish liberation leader, Mustafa Barzani. On Thursday, May 4, we planned to pay him a visit at his home in Erbil.

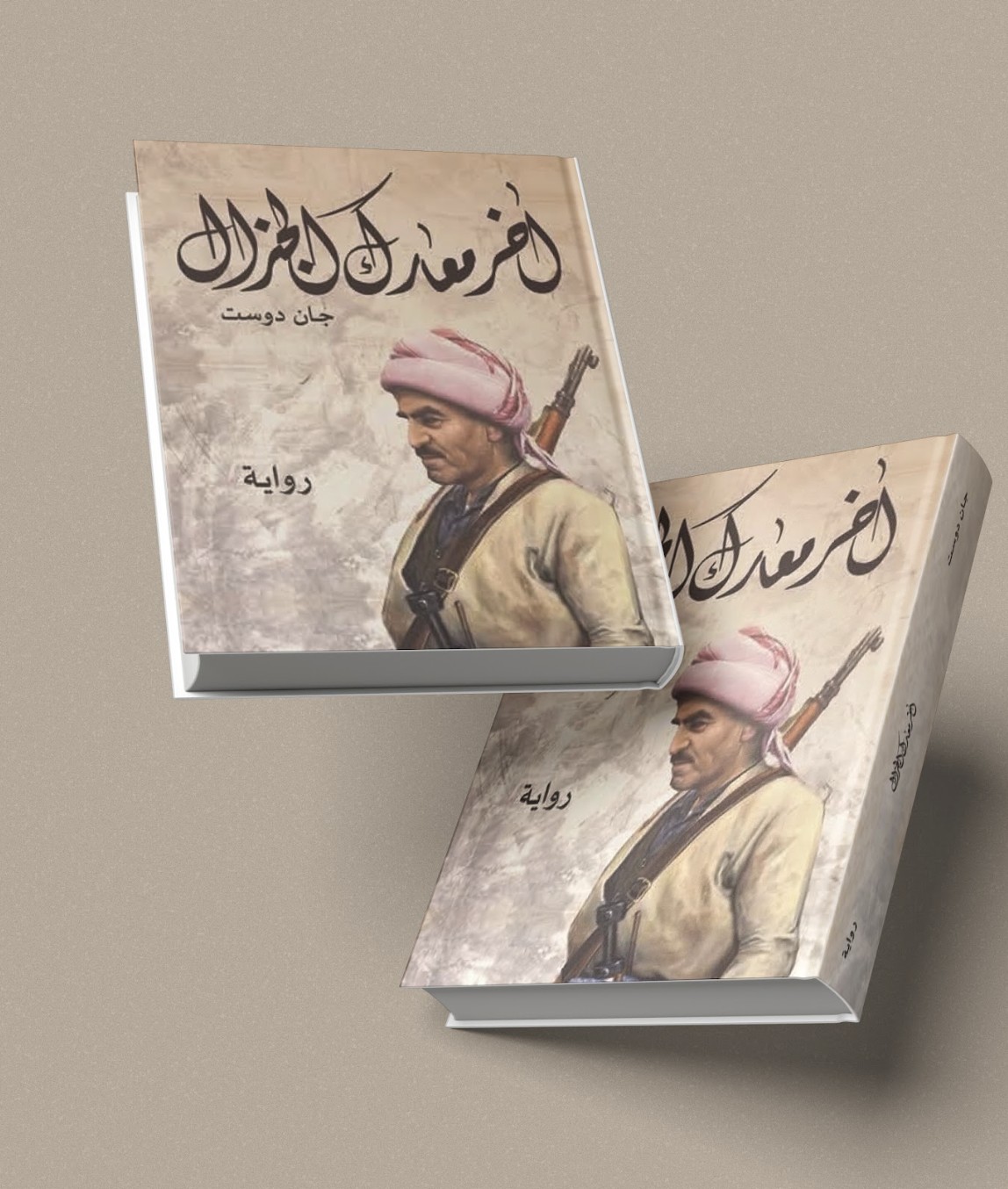

Barzani's brief stay in the hospital in Washington was very important to me because I needed documented information about those days for a prologue to my next novel. According to my colleagues at Kurdistan Chronicle, Muhsin Dizayee was one of the people who remained at Barzani’s side during his final days. I felt compelled to pay him a personal visit and hear his account of that time.

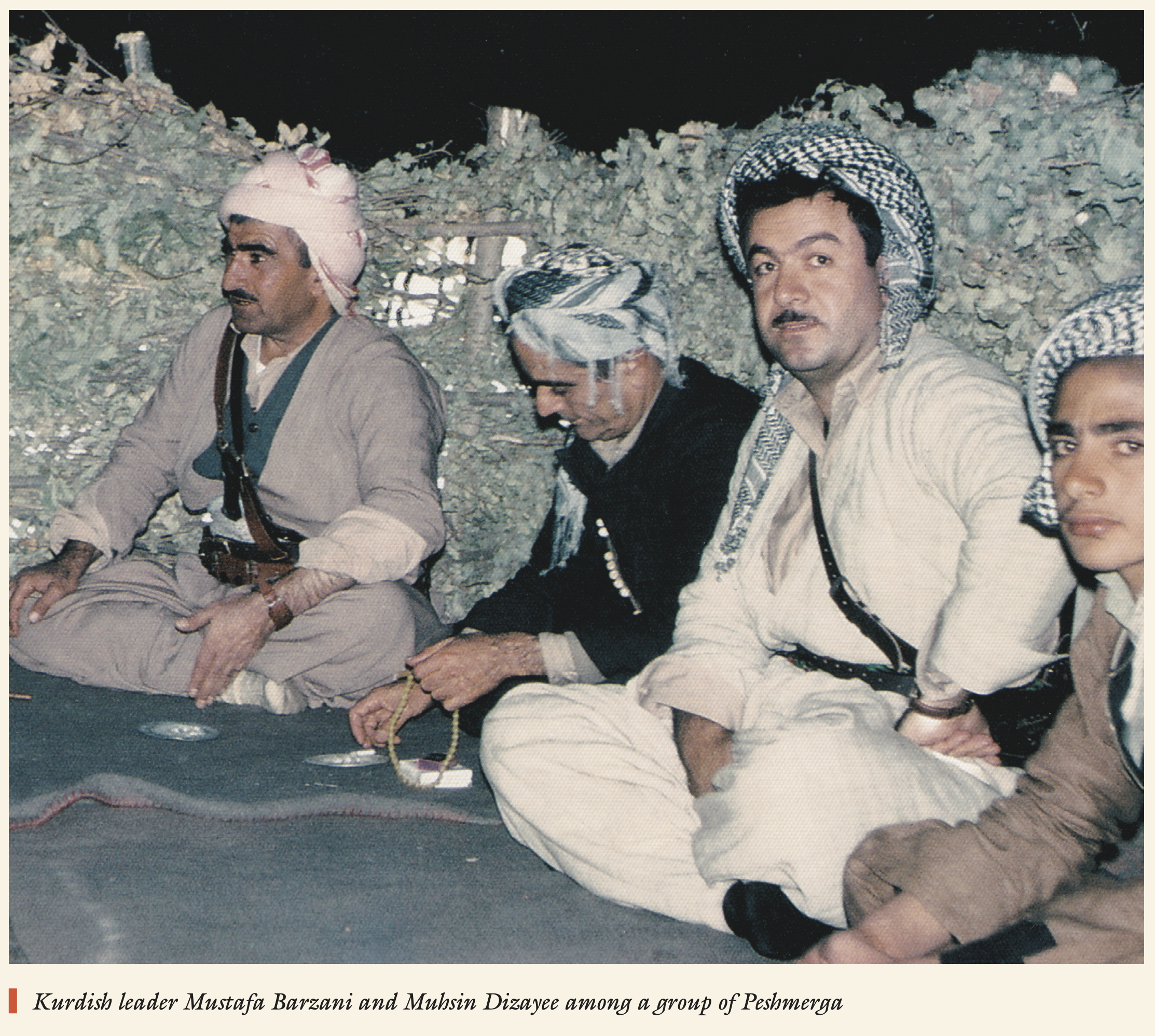

Dizayee is a veteran Kurdish politician who was a key member of the Kurdish negotiating committees that engaged with the Iraqi government from 1965 to 1966, during the tenure of Abd al-Rahman al-Bazzaz.

Following the July 1968 revolution, Dizayee served as the Minister of Northern Reconstruction in the federal government led by Abd al-Razzaq al-Nayef. From August 1973 to November 1974, he was also the Minister of Public Works and Housing, demonstrating his commitment to the development and infrastructure of the Kurdish Region of Iraq and Iraq as a whole.

However, as political circumstances evolved, he made the transition to the armed Kurdish movement, signifying his commitment to the cause.

***

We arrived on time for our visit and were greeted warmly by Dizayee's son Sherwan, who led us into the reception room. Muhsin Dizayee himself entered and greeted us warmly moments later, with a dignified bearing and impeccable attire.

I was aware that our interview time was limited. As a result, I was careful to limit my inquiries to the time he spent with the late Barzani in Washington in 1979, during the latter’s battle with lung cancer.

“Could you share your recollections of your last days with Barzani? Was he in pain?” I asked.

Dizayee raised his head slightly, closed his eyes for a few seconds as if to take a trip down memory lane, and then said:

“Barzani's spirits were high, and he didn't care about his illness. He refused to talk about his illness or complain about it in any way. When we were alone one day, I asked him, ‘Sir, are you not in pain?’ ‘Of course, I am!’ he exclaimed, laughing. ‘I experience two types of pain. A pain because I don't know what my people are going through right now, because I don't know what their circumstances are or what difficulties they are facing. Second, there is the agony of my own illness. In terms of my illness, I've learned since childhood not to show pain.’”

Dizayee paused briefly before continuing the conversation, as if he wanted to demonstrate that Barzani's concern for his people outweighed his own suffering:

“Throughout these days, he was constantly communicating with senators, journalists, politicians, and ambassadors to talk about his people.”

As we savored the delicious coffee served to us, Dizayee took a sip from his cup, and then, with graceful patience, resumed speaking. He went on to recount an event from December 10, 1976, when Barzani was invited to the Human Rights Watch headquarters in New York City. The audience consisted of journalists, ambassadors, ordinary citizens, and some senators. Barzani was asked to address the gathering, and he walked to a window overlooking the United Nations headquarters, leaving the audience bewildered. He returned to clarify, “Do you know why I stood by the window? I just saw flags from every nation in the world, except the flag of Kurdistan. There are cities in Kurdistan with populations exceeding some UN member states, yet Kurds are denied even the right to self-govern.”

Dizayee wanted to show us that the late leader was concerned about his people's welfare and did not neglect it, even while struggling with illness.

He described how Barzani delivered a comprehensive speech about the Kurdish revolution and the injustices inflicted upon the Kurds, with Muhammad Amin Dosky translating into English.

I was eager to learn the details of Barzani's final days in order to use them in my next novel, so I asked him:

“When did Mela Mustafa's illness take a severe turn?”

“His condition worsened ten days before his passing,” Dizayee responded. I was astonished by the clarity of his recollections, as he recounted events from 44 years ago as if they had occurred yesterday.

***

“Did Barzani go into a coma?” I asked.

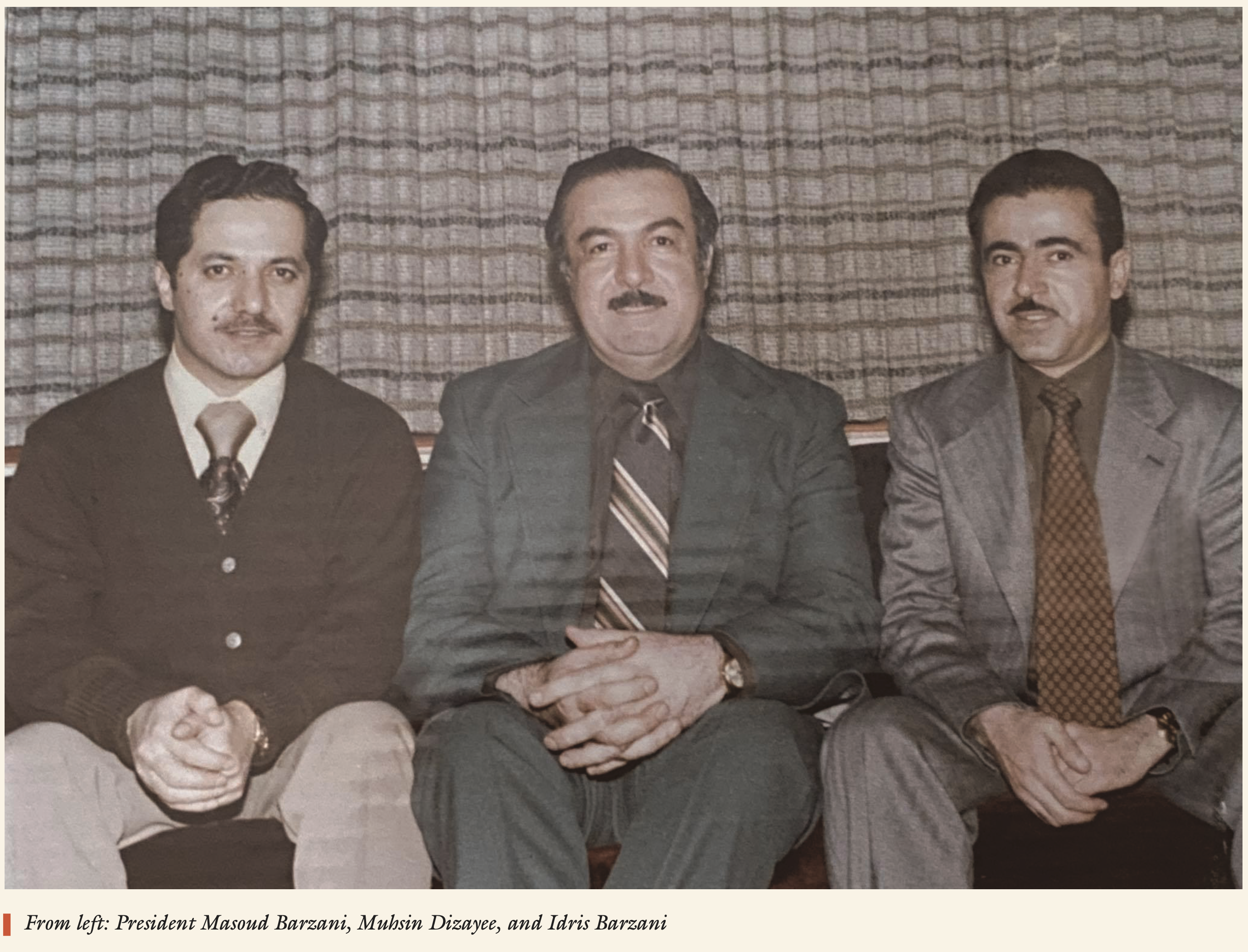

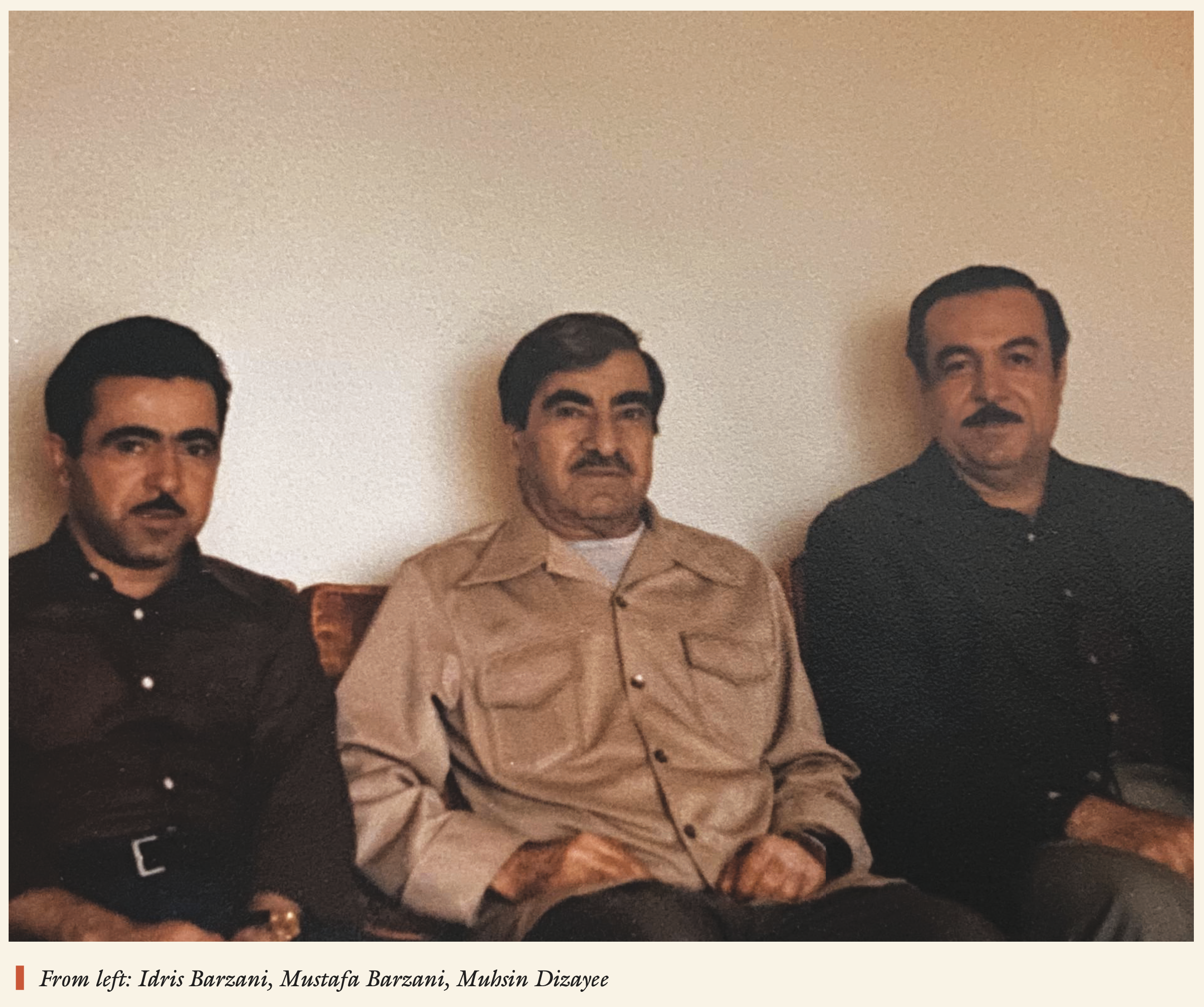

“No, he was always conscious. He spent the last four of those ten days, when he was gravely ill, in George Washington University Hospital. He had previously taken his medication at home. He was concerned that his condition was deteriorating but did not request that we take him to the hospital. We proposed it, and he agreed. His son Idris and I were there and went with him to the hospital.”

“He wasn't afraid of death, was he?” I inquired. When it comes to a man who spent his entire life facing death in mountains and caves and who had fought hundreds of battles with a brave heart and an iron will, I knew it was probably a stupid question.

“No,” Dizayee answered right away. “He used to say that death was a natural occurrence! It is a stage that comes after life. He was telling us not to be sad.”

“He used to smoke a pipe in the morning, but quit smoking a long time before his death. On the last day of his life, March 1, 1979, when the sun had not yet risen, Idris and I were with him in the hospital, taking turns caring for him. He awoke during my shift, opened his eyes, and said, ‘Why don't you sleep?’”

“I said I could not sleep. ‘Don't be too busy with me,’ he said. ‘I only have a few hours left in this world.’”

“After that brief conversation, one of the doctors arrived, performed the tests, and surprised us by telling us that his condition was stable and that we could leave. When the food was served, he ate with enjoyment, and our faces lit up. ‘I know you rejoice when I eat,’ he said. ‘I can finish it all!’”

“Idris and I were pleased and agreed to get plane tickets to leave the next day. We informed the U.S. State Department of this before leaving the hospital. An ambassador had asked me to contact him if I needed advice or if anything significant happened. I called him, explained the situation, and told him we were leaving. We waited for a representative from the Department to arrive before saying our final goodbyes.”

“Barzani sat up in bed for an hour and spoke to the State Department representative about America's betrayal of the Kurdish people. The delegate then left, and Muhammad Said Dosky and Farhad Luqman, Mustafa's grandson, arrived to look after him while Idris and I went out to reserve tickets.”

That evening, as they planned to return to the hospital, they received a call from Farhad, Luqman's son, urgently summoning them back. Tragically, upon their return, they discovered that Barzani had passed away.

***

When Dizayee reached this point in the conversation, we were overcome with sadness. So the legend, Barzani, was gone? That was his final fight in life. He fought and won many wars. He won the support of the entire world for the Kurdish cause. However, there must be a final day in the life of every human. For him, it was the first Thursday in March of 1979.

Dizayee stated that Barzani's will was for his body to be transferred to Barzan, and if that was not possible, to Iranian Kurdistan.

At this point, I had no questions left to ask. The interview was over. We stood up and said our goodbyes to the man who had been with Barzani in his final moments. I looked him in the eyes while shaking his hand. I imagined all the sad, anxious, and hopeful moments he had experienced in the last week of caring for Barzani.

I imagined Barzani saying his final farewell to the world, far from his homeland, for which he and his people had fought for more than a half-century. I imagined the pain in Barzani's heart and the dreams he had back then. I filled my mind with everything I needed to write the prologue to my new novel. When I returned from this visit, I felt as if I had visited Barzani himself, looking out at the distant mountains with his sharp eyes, full of hope, in his stronghold in Barzan.

Jan Dost is a prolific Kurdish poet, writer and translator. He has published several novels and translated a number of literary Kurdish masterpieces into Arabic.