On August 15, Syrian Kurdish novelist Jan Dost’s book Safe Corridor, set against the backdrop of the conflict in the Kurdish town of Afrin, will be published in English.

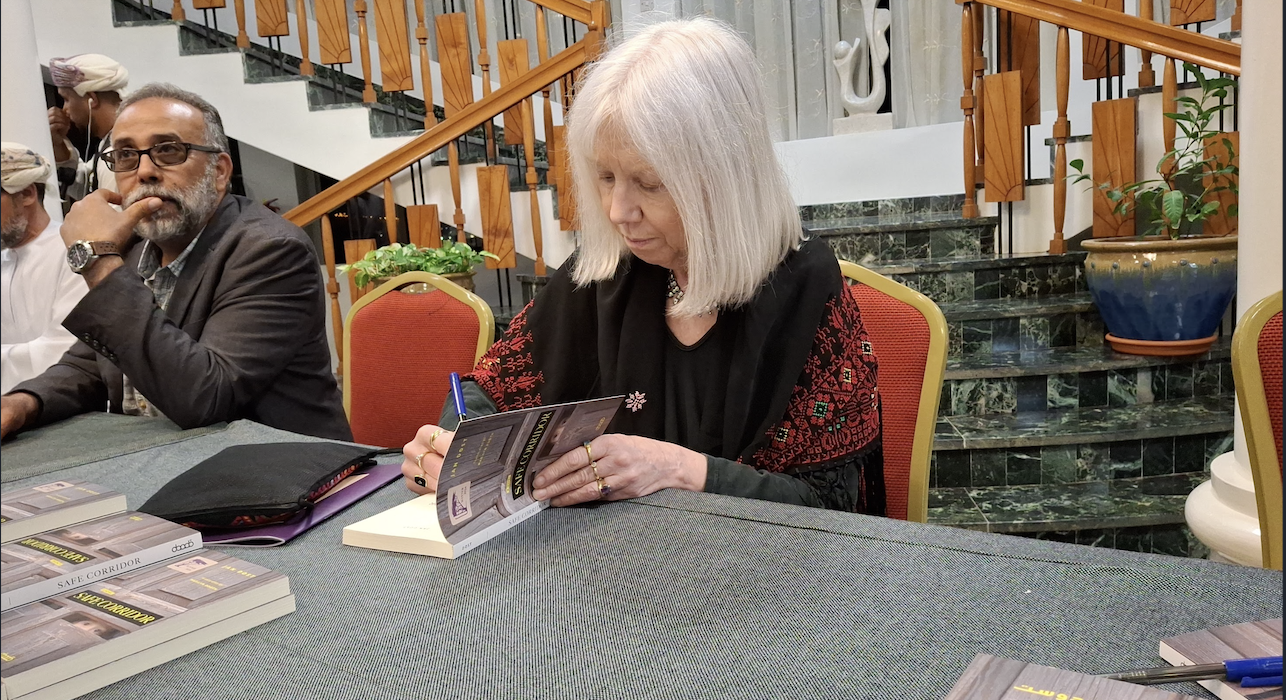

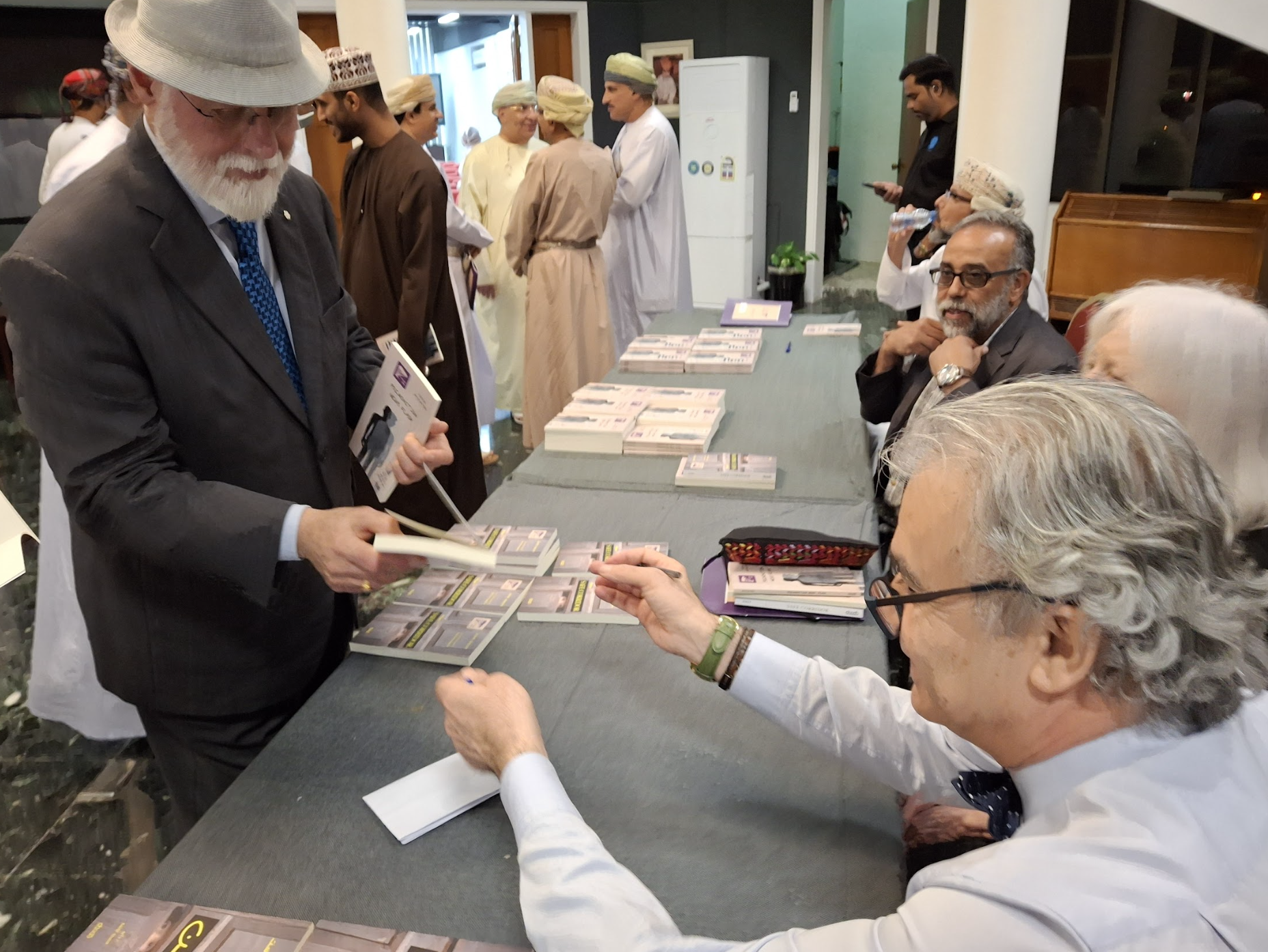

Written in Arabic in 2019 and translated by International Booker Prize winner Marilyn Booth, the book won the inaugural Bait AlGhasham DarArab Translation Prize in 2024, which recognizes unpublished book-length translations. The award includes publication by DarArab.

“In early 2019, the Turkish army and supporting military groups attacked the Afrin region of Syria, whose inhabitants are mostly Kurds. The army occupied the region, forcing Afrin’s people to flee. Safe Corridor, focusing on the ensuing violence and occupation of Afrin, echoes Dost’s earlier novel, A Green Bus Leaves Aleppo, told from another character’s perspective – an adult’s – which is significant,” Booth told Kurdistan Chronicle.

War and children

“The central character and narrator of Safe Corridor, Kamiran, is a young teenager whose father was captured by ISIS in Manbij,” Booth explained. “Later, his five-year-old sister is killed by a bomb. These traumatic events leave his mother – a language and literature professor – unable to speak. Kamiran tells of the family’s life in Manbij, Aleppo, and Afrin.”

“Kamiran (also known as Kamo) recounts how his family fled Manbij for his maternal grandparents’ home in Aleppo. But Aleppo is a war zone, so the family leaves for the house of Kamiran’s uncle in Afrin. No safety there. With the Turkish offensive, they find themselves in a refugee camp with thousands of others. The so-called ‘safe corridor’ the Turkish army promised to civilians proves anything but safe.”

Dost outlined the story’s central theme. “The novel talks about the devastating effects of wars on children. It tells the story of a young boy whose family becomes homeless because of the Syrian war.”

“The novel also highlights the long-term psychological impact, which can be compared to the physical destruction of cities and homes. Rebuilding destroyed cities is relatively easy when compared to restoring the psychological balance of children who have witnessed war firsthand,” he explained.

Dost was born in Kobani, near Aleppo, Syria, in 1966, and studied Natural Sciences at Aleppo University. Since 1986, he has worked as a journalist, translator, and editor, and has published several books about the Syrian civil war, including Kobani (2019) and A Green Bus Leaving Aleppo (2019).

“I wrote a novel entitled Kobani, about the resistance against ISIS, the destruction of the city, and the displacement of its people. This novel is one of my most important works, in which I documented the war’s effects on civilians,” Dost said.

“I care about civilians, who are the victims of all wars. My novel Safe Corridor, as well as Kobani and others, serve as a condemnation of war and a call for peace. I also wrote about Afrin because the area is close to me, and I know the suffering of its people. Many of my friends are from Afrin, and they told me heartbreaking stories about what happened there.”

A global audience

Dost first met Booth by chance. “I met Marilyn Booth in Dubai during the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature and gave her a copy of the novel. At the time, she was celebrating with the Omani author Jokha Alharthi after the publication of her translation of her novel, which won the International Booker Prize.”

“Some time later, I received an email from her expressing interest in translating my novel. I’m very happy about that. This opens global horizons for the novel, and through it, readers all over the world can learn what is happening in our country.”

Booth, the translator, hopes Dost’s book will reach the broadest possible audience. “While there has been a significant number of works published in English on the Syrian war, including political analysis, memoir, and fiction, there has been even fewer published about the Kurdish experiences,” she said.

“Although there are some excellent nonfictional analyses that draw on the longer history of Syrian Kurdish communities, there is far less fiction on the subject, as far as I am aware,” she added.

“Yet, even as the novel is set amid Kurdish communities, it is tragically universal in its focus on children as the no-longer-innocent witnesses to horror, and instead victims of it. Safe Corridor speaks to tragedies that are unfolding across our world, such as the deaths of children, whether from bombs or starvation, including every day in Gaza.”

The art of translation

Booth highlighted how every literary translation poses its own challenges, “because it conveys its own aesthetic presence which the translator hears, and feels and tastes, and is responsible to.”

“Translators are creative writers: we partner with the first writer of the text, in producing a new work. It’s also a responsibility because the translator is a reader of the text, and her translation is her reading of it … For Safe Corridor, I retained some Arabic, but not as much as in some of the other novels that I’ve translated.”

“The biggest challenge in this novel is the narrative voice. Kamiran’s voice frames the narrative. He is a feisty, growing young teenager who is – by his own admission – a garrulous, unstoppable chatterer, in a tragic context where sometimes speech is impossible. I had to think a lot about how Kamo would speak in English. He hears and reproduces a lot of adult language, but in the end, he is still a kid.”

“I didn’t want to make him sound too adult or too childish. But of course, wartime forces children to ‘grow up quickly,’ if that’s the right way to put such a tragic development. Kamo can be rude at times, yet amid the horrors he experiences, he’s also conscious of certain limits, even in a social context where violence seems to remove all such limits.”

Another challenge Booth faced in translating was the politics of naming, especially for cities and towns. “The Syrian state had tried to erase Kurdish town and village names. In a translation, what does one use: names by which the towns are now mostly known or earlier names? I followed the lead of the Arabic version … but of course, readers of the Arabic might spell – or ‘think’ – those names differently depending on their own linguistic, social, and ethnic identities,” she explained.

Booth, furthermore, said that one of the reasons she loves this novel is that it poses a juxtaposition of the everyday and the horrific, which takes form in a somewhat surrealistic register.

“In Kamo’s narration, utterly gruesome images of war mirror his own transformation, as he witnesses himself turning into an inanimate object, and produces a grim, even macabre humor. But of course, there’s nothing humorous about objectifying – in every sense – people in war. His self-examination also entails overheard accounts of people’s wartime lives as they undergo multiple displacements and exploitations. These ‘flat’ narratives of horror are difficult to tell, and difficult to translate,” Booth said.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg is a seasoned reporter and analyst who specializes in Kurdish affairs, and holds a Master’s degree in Kurdish studies from Exeter University, UK