It began like any other day. He checked his phone for emails, as many of us do, and found a message from World Press Photo, often called the “Nobel of Photography.” At first, he assumed it was a routine update for subscribers. But as he scanned the text, he realized he had just won the World Press Photo Contest for 2025 – a dream he had pursued for years.

“I felt numb for a while. I didn’t want to read the email again out of fear I had misunderstood it,” said Kurdish photographer Ebrahim Alipoor. He described feeling a mix of joy, confusion, and restlessness, explaining to Kurdistan Chronicle how he had been outside his home, trying to spend some time alone, when he learned he had won the world’s premier photography contest.

“After a while, I did reread it, this time much more carefully. The email said that my documentary photo story about the Kurdish kolbars – the cross-border laborers who carry goods back and forth across the borders of Iran, Iraq, and Turkey – had won the award. But I was instructed not to tell anyone until the foundation had concluded its final evaluation to confirm the authenticity of the photos.”

His story was selected from among 59,320 entries submitted by 3,778 photographers from 141 countries.

For Alipoor, the victory was a turning point. He had devoted himself for 13 years to the project “Bullets Have No Borders.” The award placed him among the top international photographers while shining a light on the harsh living conditions of Kurds in the border regions of Iran, which was his primary goal all along.

“Bullets Have No Borders”

In 2012, Alipoor embarked on the journey without knowing how long it would take. As a young Kurdish photographer living in Baneh, Eastern Kurdistan (northwestern Iran), he had witnessed and experienced the economic hardship of his people. He could not just ignore how decades of unemployment had forced locals to risk their lives as kolbars for a small income.

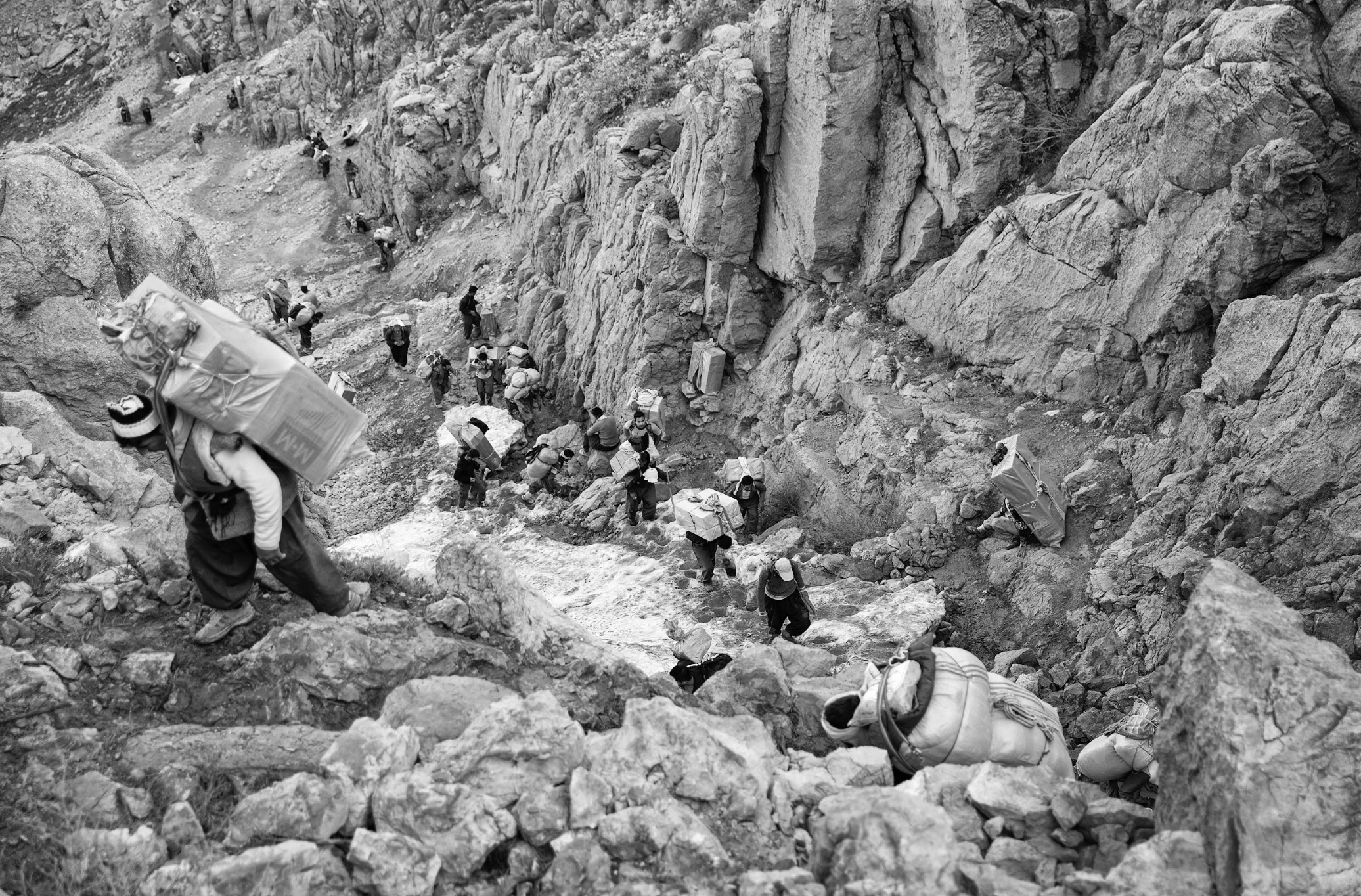

Kolbars carry goods such as household appliances, mobile phones, and clothes, on their backs through rugged terrain from Iraq and Turkey into northwestern Iran. Their work is perilous: if they can evade the border guards, they still face a range of obstacles, including land mines, avalanches, falling from high cliffs, or simply losing their way in a no-man’s land.

Alipoor felt personally connected to this struggle. He knew many of those who had lost their lives while carrying goods.

“Many of those in my photo story are my family or friends. They are my people,” Alipoor said softly, his words tinged with sorrow. “And that’s what art should do: carry a message and document history through an artistic lens.”

Alipoor insisted on putting forth a correct understanding of his award-winning photo story. It was a work of art in its own right, but also a testimony to the human costs of kolbari: families mourning loved ones, a young widow mourning the loss of her husband shortly after their marriage, a child guiding his blind father who lost his sight in a land mine explosion.

“The scale of the tragedy is larger than what an individual kolbar endures,” Alipoor stressed, arguing that this harsh reality made him include only four pictures of the kolbars themselves within the 30-photo collection. “The rest illustrate the difficulties faced by their families, and the entire community in general.”

Browsing through the photo story, one can understand that behind the camera, a tragic story was also taking shape for the photographer. He often spent days with each family in his photo story learning about their daily ordeal so that he could narrate their story with the utmost honesty.

“There were days when I would visit a kolbar family and not take a single photograph. I would talk with them while drinking tea and preparing lunch, trying to learn more about them and connect, all to build an atmosphere of comfort so they could open up to my audience. I wanted to help them to tell their full story in front of my camera, all in one single frame.”

A 13-year quest

Throughout the years of hard work for this project, Alipoor exceeded his role as an artist, becoming an advocate for the marginalized people he depicted. He once helped raise funds for Ahmed, a Kurdish kolbar suffering from frostbite after he lost the path in the rugged snowy mountains between Iraq and Iran. Ahmed eventually lost all his fingers because he could not afford surgery in Tehran.

“After the fundraising, I accompanied him to Tehran. The day before his surgery, he went to use the bathroom. Just as he reached the door, he burst into laughter. Confused, I watched as he came back and held out a small piece of his finger, completely blackened. ‘This was the last finger I had left,’ Ahmed said, forcing a smile, ‘I lost it while trying to open the door.’ For a few moments, silence filled the room. Then he broke into tears.”

Alipoor also explained how deciding on the photos and their sequencing so that they told coherent stories was just as difficult as taking them.

“There are many other photos that might be more visually appealing, but not as impactful as what you see in the final collection. The contest itself imposes many strict requirements that I had to keep in mind while selecting the photos,” he elaborated.

“Sometimes, I had to consult colleagues when I could not decide on my own. I would exclude a photo because of a bad experience I had on the day it was taken, but the second opinion from someone not weighed down by the emotions of that day could help me make the right decision.”

The big day

Not long ago, winning a prestigious top photography contest was an unrealistic dream for Alipoor, but looking back, he believes this struggle made his award even more meaningful.

On the day of the award ceremony, he felt joy and pride, but also the grief of the people he had introduced in his photos.

“It was an incredible moment on the stage. The comments and feedback were heartwarming. Even today, I receive messages from people. This encourages me to dream even bigger.”

In a World Press Photo video published on YouTube, jury chair Laura Boushnak praised Alipoor’s courage in documenting such a difficult story.

“I was intrigued by the photographer’s approach. It’s the kind of project that you need to slow down to look at. The images are stunning. And what stayed with me [was] those close-up shots where the photographer is trying to tell us something very specific,” Boushnak said.

“It’s not an easy story at all. He took a huge risk to publish it. I’m always interested in how photographers find ways to illustrate difficult topics visually.”

The Nobel of Photography

Founded in the Netherlands in 1955, World Press Photo is a nonprofit organization that “champions the power of photojournalism and documentary photography to deepen understanding, promote dialogue, and inspire action.”

It is considered the world‘s largest and most prestigious annual press photography contest, often referred to as the Nobel of Photography.

Each year, a jury of 10 members awards the World Press Photo Story of the Year to a multi-image story that explores a theme of social relevance distinguished by photographic intensity and the importance of the content. In addition to the top two prizes, three single photo prizes and three-story prizes are also awarded in eight categories.

In 2024, the World Press Photo exhibition attracted over 3 million visitors in 144 countries, with more than 4 million people joining the online exhibition. For Alipoor, the ultimate prize is the opportunity to tell the story of his people to a global audience.

The man behind the camera

Born in 1990 in Baneh, Eastern Kurdistan, Alipoor grew up in a region shaped by social and political complexity and economic hardship. Photography became his way to express himself and to narrate the underreported hardship of the Kurds in Iran while also celebrating their cultural heritage.

His work has been exhibited internationally and has won several awards, including Asia Portraits 2024. He has also contributed to several films and produced three documentaries.

Yet Alipoor does not view his latest honor as a finish line. He wants to inspire other Kurdish photographers – and artists working in other mediums – to tell the untold stories of their people.

“Kurdish photographers should move beyond capturing scenes that are simply pleasing to the eye. They should document their history and become a messenger for what their people want to say.”

Sardar Sattar is a translator and journalist based in the Kurdistan Region. He has translated several books and political literature into Kurdish and English. He writes regularly for local and international newspapers and journals.