Just 22 kilometers southwest of the bustling Kurdish capital of Erbil lies Kurd Qaburstan, one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in recent Mesopotamian history. Spearheaded by Associate Professor Tiffany Earley-Spadoni from the University of Central Florida, this groundbreaking excavation is not only rewriting what we know about the Middle Bronze Age, but also shedding light on the ancient urban powerhouses that once thrived in Upper Mesopotamia.

For decades, the historical narrative of Mesopotamia – often referred to as the cradle of civilization – has largely centered on southern Iraq and the famed cities of Ur, Uruk, and Babylon. Northern Mesopotamia has remained a relative mystery.

Kurd Qaburstan is changing that.

“This is the jewel of the Erbil plain,” says Earley-Spadoni. “We are uncovering a city that flourished around 1800 BC, a site we believe to be the ancient city-state of Qabra, known from powerful historical inscriptions.”

Spread across more than 100 hectares, Kurd Qaburstan is among the largest archaeological sites in the region. Thanks to innovative geophysical methods like magnetometry, researchers have mapped roughly 80% of the city, revealing monumental architecture, residential neighborhoods, complex drainage systems, and wide boulevards.

Echoes of a violent siege

The site is believed to be ancient Qabra, a prominent city referenced in two major inscriptions: The Stele of Dadusha and the Stele of Shamshi-Adad. These texts recount a dramatic siege led by a coalition of kings that ended with Qabra’s destruction. The name, once shrouded in mystery, is now backed by compelling archaeological evidence.

“There’s a striking match between what we’re excavating and what’s described in those ancient texts,” Earley-Spadoni tells Kurdistan Chronicle. “Massive palaces, signs of violent destruction, and its location between the Upper and Lower Zab rivers; it all points to Qabra.”

Two large palace structures have been uncovered, one on the lower mound and another on the upper mound, each roughly a hectare in size. The lower palace has revealed chilling evidence of its downfall.

“We found over 16 articulated human skeletons in the rubble of the palace,” she explains. “These weren’t ceremonial burials, but people caught in a moment of catastrophe, perhaps during the siege. It’s rare to see warfare’s human cost so vividly preserved.”

At the same time, excavations in residential neighborhoods are painting a richer picture of daily life. Far from being a city of extremes, Qabra appears to have had a relatively balanced society.

“We don’t see signs of great poverty. People living in these houses had access to the same types of food and tableware as those in the palace,” she notes. “It tells us something remarkable: this was a well-organized and relatively prosperous society.”

Streets were paved with pebbles, and houses had functioning drain systems. There was a clear sense of urban planning, even if elements of the infrastructure seemed improvisational. “We’re seeing a level of civic cooperation that suggests local-level governance and community participation,” she adds.

An archive of ancient life

A temple uncovered at the site offered tantalizing clues about religious life. Bones from sacrificial lambs, ceremonial trays, and massive storage jars point to a thriving ritual space. However, the deity to whom it was dedicated remains unknown.

“We have all the markers of temple activity, but no clear inscriptions about the god worshiped there,” says Earley-Spadoni. “It’s one of the enduring mysteries we hope to solve in future seasons.”

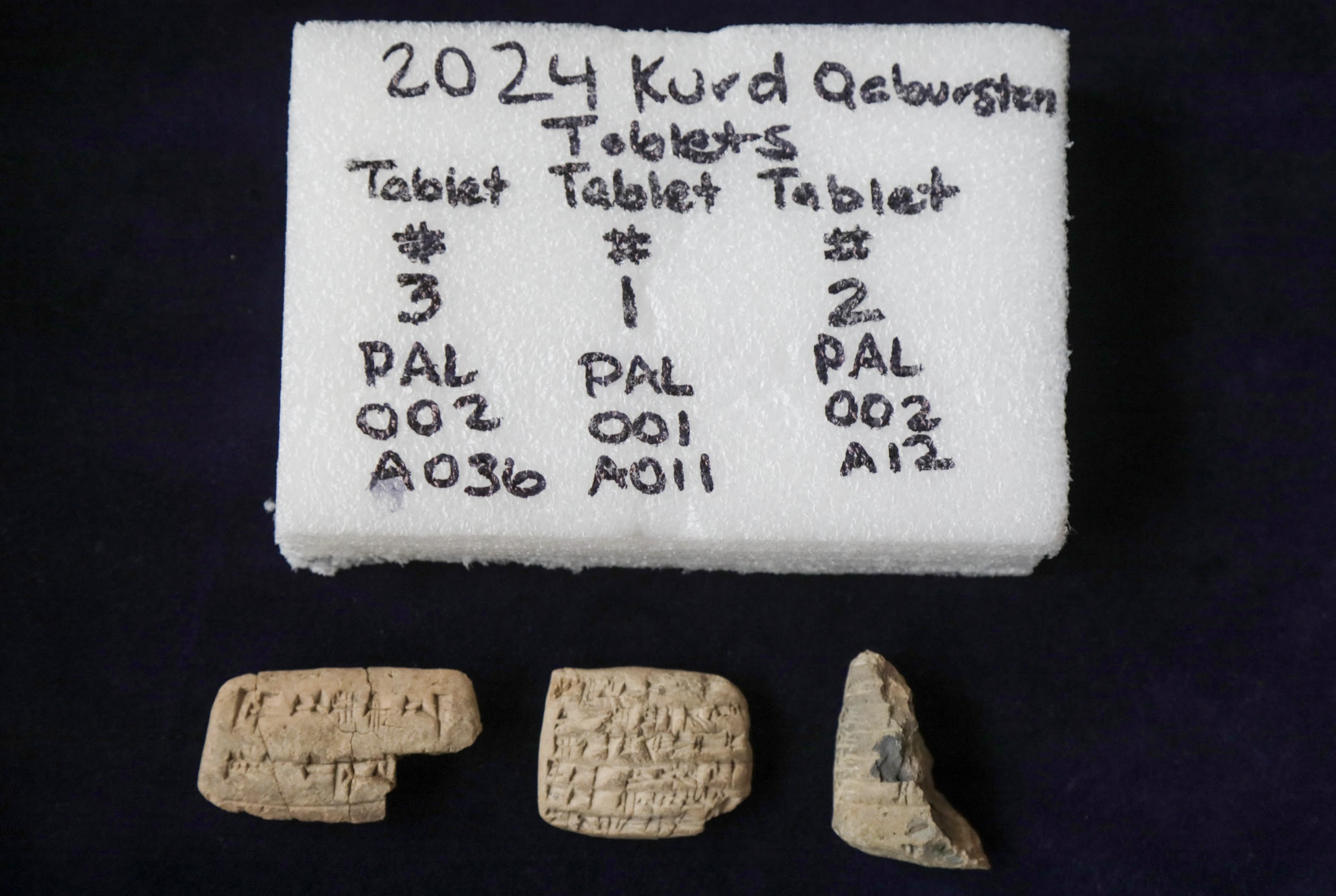

Perhaps the most exciting find has been the discovery of a cuneiform archive: the earliest and largest of its kind yet found on the Erbil plain. Excavations have revealed at least 18 tablets this season alone. Though some are still undergoing conservation, a few have been translated.

“We’ve found administrative documents, receipts, and records of barley transfers. They’re basically 4,000-year-old bureaucratic forms,” she says, examining cuneiform tablets discovered at the site.

Some tablets may soon offer deeper insight into social identity, depending on the names and language they contain. “If we find Amorite or Hurrian names, that helps us understand how people identified themselves and their connections to wider cultural traditions, whether they were northern, as in ancient Mari, or southern, as in Babylonia.”

The destruction of Qabra, as recorded in cuneiform and confirmed through excavation, gives scholars a rare opportunity to study the effects of ancient warfare on urban populations.

“We tend to read about war in the abstract, but here, we see its toll: families killed, cities burned. It’s a deeply human story,” says Earley-Spadoni.

The city’s fate also reflects a broader geopolitical transition. The Middle Bronze Age (2000-1600 BC) was a time of powerful city-states, with Qabra among them, but the era ended with the rise of empires, shifting the political landscape forever.

“This site helps us understand how Mesopotamia evolved from a land of independent city-states into an imperial world. It’s a crucial piece of the puzzle,” she emphasizes.

The Kurd Qaburstan Project is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and led by a diverse international team. Originally started by Dr. Glenn Schwartz of Johns Hopkins University in 2013, the project has been under Earley-Spadoni’s leadership since 2022. She brings deep expertise in Mesopotamian and Syrian urbanism and a passion for storytelling through archaeology.

As more cuneiform tablets are deciphered and excavation continues, Kurd Qaburstan promises to remain a touchstone for understanding the roots of urban life, governance, and human experience in ancient Mesopotamia and is a pivotal chapter in Erbil’s 5,000-year-old history.

Qassim Khidhir has 15 years of experience in journalism and media development in Iraq. He has contributed to both local and international media outlets.