It’s been more than ten years since I read My Father’s Rifle, written by the Kurdish author and director Hiner Saleem. The complicated emotions I delved into are still so vivid, as if I’m still experiencing them today.

I was fortunate to be among the early readers of his latest novel My Ashes, Golda, and the Others. As I finished it, my heart was shattered by the stories I had become a part of; yet, I felt myself carried away, drifting like ashes in the wind.

In My Ashes, Golda, and the Others, our protagonist Dilman decides to end his life and writes in his will that his body is to be cremated and his ashes to be taken to his mother’s grave in the city of Akre in Kurdistan. The adventure begins as Dilman packs his own ashes in a pickle jar and searches for someone to fulfill his last wish, someone who can understand his will, someone who won’t blame him for his suicide, and someone who will respect his decision to cremate his body despite being a Muslim.

I find myself thinking that sorrow is a burden that weighs on each of us. It is universal, present in every language and every culture. It needs no elaborate explanation; it simply exists, raw and unmistakable, deep within us – in our palms, our eyes, and at the tips of our toes. This pain doesn’t require fancy words to be understood; you just feel it so poignantly.

Throughout my reading journey, I was immersed in sorrow. What I was reading were the disappointed stories of the Kurds who live not far from where I live as a Kurd. Although I’ve never been in exile and have never been forced to migrate to another country, I found myself deeply connected to Saleem’s journey. Being an immigrant – without a country – is a place beyond my imagination. However, the dream of building a homeland with one’s own hands, only to watch it remain unfulfilled, is painfully familiar. Hiner Saleem has been living in exile in France for many years. However, the concept of exile can be used interchangeably in this context, as the novel can also be interpreted as autobiographical. As a reader, I was able to be a part of Saleem’s exile.

Dilman, whose body was cremated just as the work week ends on Friday, asks the crematorium worker if he will turn off the furnace. The man replies that he can only collect the ashes on Monday, to which Dilman replies: “But Mondays always come very late in Paris.” Though I have never been in exile, I felt the ache of those words, as if a blow had struck both my head and my heart.

In both of Saleem’s novels, the stories are built upon the ancient sorrow and disappointment of the Kurds, but it is infused with subtle humor. In My Father’s Rifle, the reader first encounters a naughty joy intertwined with hope. The hints of joy throughout envelop the spirit of Saleem’s stories. Even though My Ashes, Golda, and the Others also begins in hopelessness, the humor still resonates. From his witty remarks about his mother’s excessive religiosity to his friend Miso’s home in Italy – jokingly called ‘the White House’ – Saleem weaves humor into the despair of his characters’ experiences. Even the electricity cuts, caused by the visits of the Syrian President’s brothers to their mistresses, become a source of dark comedy.

Throughout the book, Dilman carries the jar filled with his own ashes, and through it, recounts the events that followed his forced departure from Kurdistan, all with a sharp and witty tone. Yet, the jar holds more than just ashes – it holds the remnants of our hopes that were buried in history’s forgotten corners. What’s inside the jar is the relief that our people have been barred from for many years. The jar contains the pomegranates from our cherished garden, the last touch of a mother’s hand, and the final glimpse into the depth of her heart. Now, I see those ashes as the embodiment of all cultures that could not find a place to call home. As I immersed myself in these stories, I realized how masterfully Saleem conveys emotions that are universally human.

The tales inside the jar are overwhelming, and I’m fully aware of this. But once the jar falls to the floor, the ashes disappear into eternal emptiness. We, too, flow away with each speck of dust.

And so, I leave a few words for Dilman as well. While we struggle to open the jar’s lid to free all our belongings, you must stand with us. Long live Dilman!

---

These were my initial thoughts on My Ashes, Golda, and the Others as the editor of its Turkish translation.

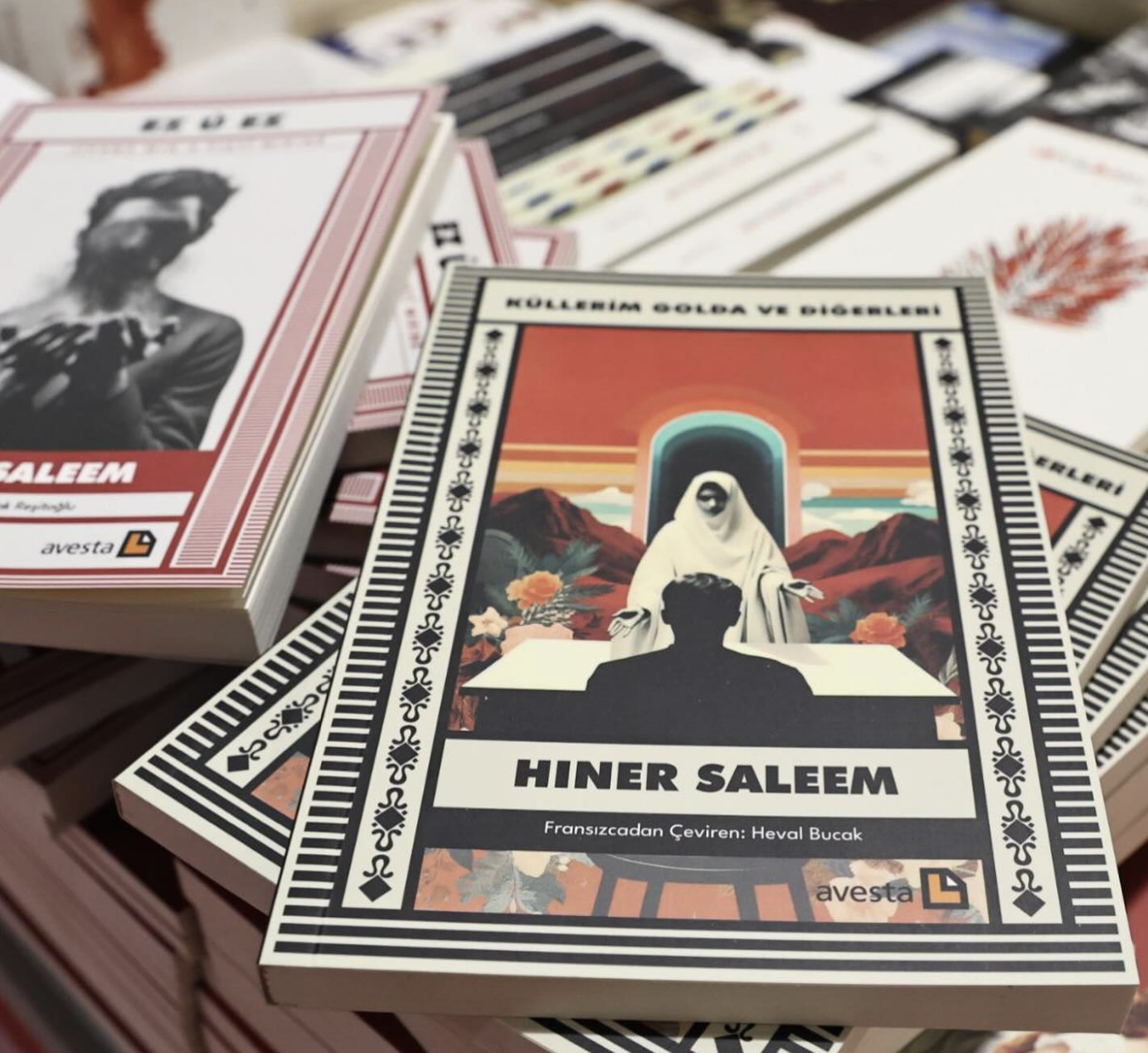

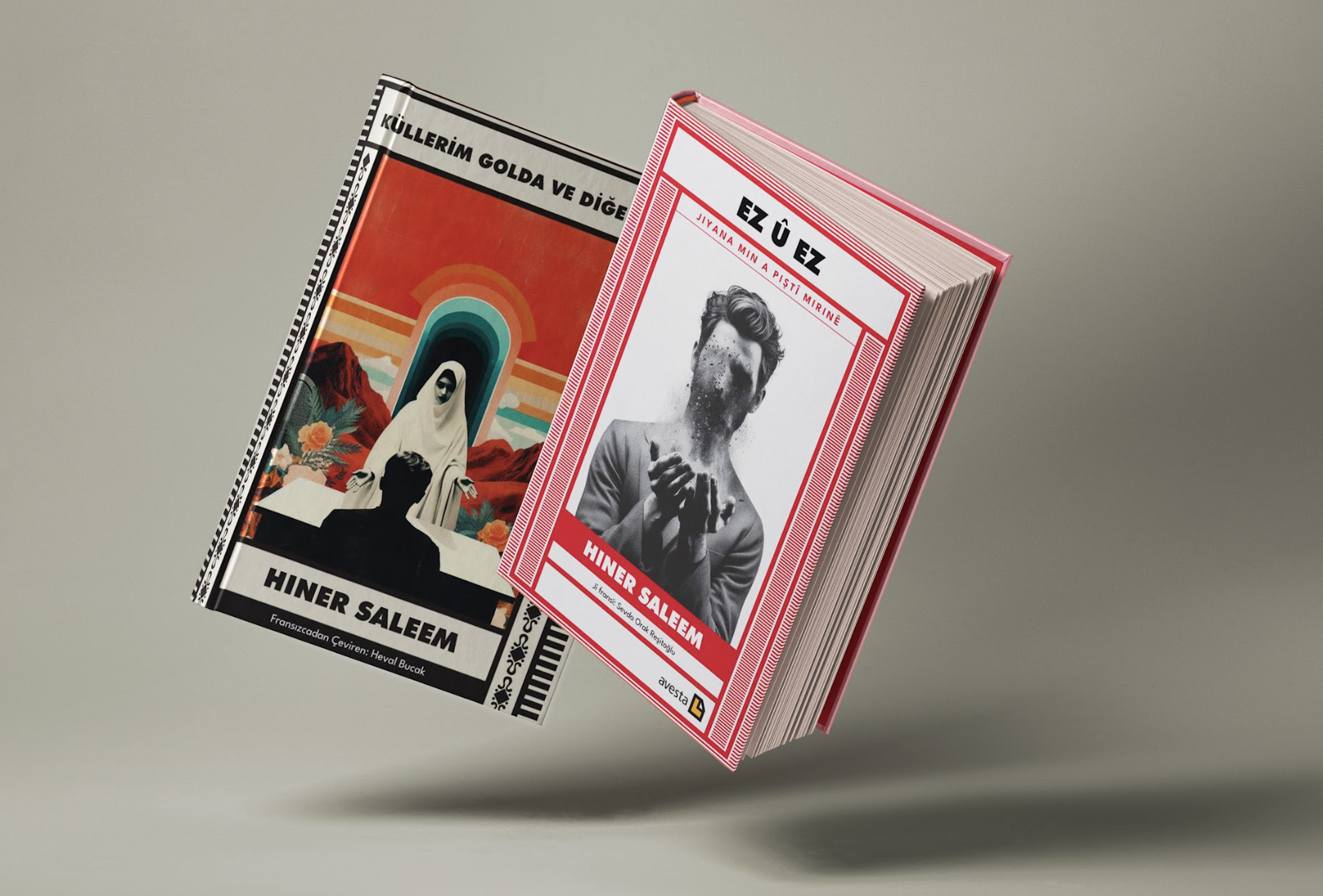

Known for his internationally acclaimed films Vodka Lemon and My Sweet Pepperland, as well as his debut novel My Father’s Rifle, which has been translated into more than 30 languages, Hiner Saleem now returns with a new novel. He originally wrote My Ashes, Golda, and the Others in French, but Avesta Publishing simultaneously translated the novel into both Turkish (Kullerim Golda ve Digerleri) and Kurdish (Ez u Ez), releasing both editions at the end of 2024.

Beyond reading the novel, I had the opportunity to engage in a deeper conversation with the author. In the following interview, Saleem graciously answered my questions, offering insight into his writing, his characters, and the themes that shape his work. I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to him for his time and generosity.

During our conversation, you will come across some French and Kurdish expressions. I have intentionally left them unchanged, as these words best reflect the author’s thoughts and emotions in their most natural form. Given the multilingual nature of both Saleem’s life and work, preserving these expressions felt essential. I would also like to express my gratitude to Abdullah Keskin for his assistance during and after the interview in transcribing and translating Saleem’s Kurdish expressions.

---

Gul Hur (GH): Let me begin by congratulating you on your latest novel. As the editor of its Turkish translation, I’ve had the privilege of witnessing a small part of its journey and have seen firsthand the exciting process you’ve gone through. I’m curious about your writing journey. In My Ashes, Golda, and the Others, the protagonist Dilman’s story starts with his decision to end his life. What inspired you to explore the theme of suicide?

Hiner Saleem (HS): I think if you’re Kurdish, you are born with suicide. So, I wanted to talk about it through the eyes of someone who is born, who is alive, and yet experiences deprivation (mahrum kirin). I needed to find a way to talk about these things without taking myself too seriously. To speak about what really matters to me, I need humor. I need absurdity. I need to find a form, a way to express it.

And nostalgia is a part of it. At the very least, there is a person in my head, the most optimistic side of me, the part that is dead. And that part? It expects nothing. Ew alema mirî pir rehet e, alema sax muşkile ye. (The dead side is at peace; the living side is in trouble.) The side that is alive, though, is full of struggles, pessimism. But the dead side, it’s strangely positive.

So, suicide, in a way, is an indirect way of expressing that if a person is not free, or if they are a minority among the savage parts of humanity, they feel like they are dying. Every day, they think about suicide. But in a literary sense, suicide is also a powerful artistic pretext. A way to talk about life itself. And in that, there is beauty. There is hope.

GH: Did you experience something like this yourself, or was it purely in your mind?

HS: Honestly, I think I would kill everyone else before I’d ever consider killing myself. Absolutely not—ez ne wisa tirsonek im ku xo bikuşim (I am not so much of a coward that I’d kill myself). No, suicide is something very distant from me. And maybe because of that, it was easy to write about.

If I were actually suicidal, I’d have written like a French intellectual suffering from constipation, talking endlessly about frustration and suffering like they do. But fortunately, because I don’t think about suicide, it was just a form, a pretext. That gave me the freedom to write about it however I wanted. To use it as I saw fit.

In a way, I’m saying: I’m alive, but I understand that there is no hope. And yet, I remain pessimistic – with a smile. But the ashes, they are my small remnants of optimism. It’s a contradiction. And to some people, it might just seem absurd, meaningless. But that doesn’t matter.

Because before literature is sociology, before it is narrative, it is art. And art is free. It has no borders. Take Marc Chagall, for example. He’s one of my favorite painters. He was Jewish, originally from Ukraine, but in the 1920s, he fled Bolshevik Russia and came to France. If you look at his paintings, you’ll see a Jewish man floating above a village. In reality, of course, people don’t fly. But in art? He can fly. Or in movies, we see someone jump out of an airplane, float in the sky, then climb back inside. None of that is real. Or maybe someday it will be, but that’s not the point. It’s art. That’s how I see literature. It’s art before it’s sociology. Before it’s narrative. Before it’s history. If I wanted to write sociology, I’d write a book about Kurdish history, about what happened in Turkey. But I don’t want to. That’s not my job. That’s the job of intellectuals.

GH: In what ways do you use the theme of suicide to explore life?

HS: Which life? We grow older, we slowly start to say, okay, now I need to pause, to try to understand what happened before. Why did I end up here? Where am I? Why did I come here? What happened in the past? The people I love or hate, what role did they play in my life?

And, you know, this book is a mosaic. I talked about everything. When it comes to traditional novel structures, I broke the conventional alphabet of storytelling. Have you ever seen a hand-knitted pullover? Blûzên daykên me bi destan çêdikirin, gava davekî jê vedikî, hemû vedibe. (Our mothers used to knit sweaters by hand. If you pulled one thread, the whole thing would unravel.) That’s what I wanted to do with my life, to pull at it and watch it come apart, to trace it back.

GH: So, you pulled on a thread, and the rest followed?

HS: The rest was already there. But I can’t say it ‘came’ – it was always there. I just had to open it up. Welatek an kesek zilmê li miletekî din an insanekî din bike, ez vê tucar nikarim qebûl bikim. (If a country or a person oppresses another country or person, I can never accept that.) I see this as my personal struggle because I love myself. I can never accept someone telling me, ‘Your language is forbidden.’ Who are you to say that? How is that possible if you are a human being?

And how do people survive in secrecy? For a hundred years, Kurdish people have lived like that. I’m speaking on a human level, I’m not being political. Everywhere we go, there are guns pointed at us, ready to fire. Why? I refuse to accept this. I take great pride in my dignity. Not in being Kurdish, because that’s not something I made. I can only take pride in something I create. But at the same time, I feel no shame about it either. I am Kurdish. Noqda (That’s it). It’s not good or bad, it simply is. If I were Senegalese, I would say the same. If I were Turkish, I would say the same. But why, because I am Kurdish, must I face all these difficulties? Why couldn’t I see my mother for twenty years? This is a struggle for freedom – for the affirmation of my freedom.

And sometimes, I just want to cry. When I hear a Kurdish song, for example, one from the Caucasus, I cry.

I think, If I had grown up in Kurdistan, like everyone else, maybe I would have fallen in love with a girl from there. Maybe I would have done this, maybe I would have done that. But why was I deprived of this? Ez mehrûm kirim (I was deprived). Why did they take my roots from me? It sounds like a rebellion, against nostalgia, against the past and the present. As my grandfather said: ‘No future. Fortunately.’

GH: I’d like to talk more about your writing style. I sense that you deliberately avoid being overly dramatic or tragic. Instead, you express your emotions – what you truly want to say – through humor. I can see and feel humor in your writing. Is this something you intentionally want readers to notice? Can you share more about your writing style?

HS: Humor is full of tragedy. L’humour est la politesse du désespoir. (Humor is the politeness of despair.)

With humor, you can say things that people wouldn’t normally accept or receive well, but they will still read them. If I wrote seriously about the Kurdish experience, nobody would read it because it’s too sad. So, I have to find a tactic, a way to talk about this bordel (mess). Ez ditirsim her gav dîqat dikim ku ew tiştê ez dinivîsim hestîgiran nebe. (I’m careful to make sure that what I write doesn’t overwhelm the reader.)

I don’t like to deliver direct messages, but humor allows messages to pass through more easily, and in my life, I need humor. I can’t be around people – friends – if they don’t have humor. I think people who have suffered a lot throughout history develop a kind of tool for survival. And that tool is humor. Look at Jewish people – they have jokes about the Holocaust, about gas chambers. There are entire volumes of Jewish humor and jokes. I think Kurdish people have their own kind of humor to indirectly talk about what has happened to them.

Humor is also hope. Because if someone has humor, it means they believe in something. It means they have hope. I keep repeating this, this relationship between hope, humor, despair, tragedy, nostalgia, and exile. Exile is something deeply embedded in me. There’s a difference between being an emigrant and being in political exile. If a Turkish person moves to Germany, they are an immigrant. They go there to earn money, to build a better life for their children and family. But for me and for most Kurdish intellectuals, we didn’t go to European countries to look for jobs. Especially in the 1980s and 1990s, it was the worst period for Kurdish people, whether in Turkey or Iraq.

I grew up in the 1980s. I was a teenager then. I saw all of it. What I write, it has to reflect me. I’m not afraid to write about very personal aspects of my life. I have no shame. I don’t want to write in a politically or intellectually correct way. I don’t like the classic, structured approach because it feels like a catalog on how to write a novel. I do the same in cinema. My filmmaking style is full of ellipses. In France, people call me the king of ellipses in cinema. I jump from one subject to another, then circle back later.

There are other things that are very important in a novel. One is music, the rhythm of the writing. It has to feel like a song, like a symphony. It has to have an ambiance. In a movie, painting, or novel, there must be some magic that passes through it. If there isn’t, then it’s not art. I don’t claim to achieve all of this. But maybe, just maybe, I do something. And ultimately, it’s not me who decides. When I finish a movie or a novel, it’s no longer in my hands. I always believe what the audience says. I may not agree, but they are free.

A novel is what the reader feels when they read it. I can’t tell someone, ‘You’re an idiot. You don’t understand. Let me explain what life is.’ No. If someone comes out of a movie and says, ‘That film was really bad,’ I say, ‘Thank you very much.’ And if another person says, ‘It was amazing! A masterpiece,’ I say the same thing. It doesn’t affect me. Of course, I prefer it when people say it’s amazing or beautiful, but if someone thinks it’s bad, then okay. If that’s how they feel, then they’re right, for them. That doesn’t mean the film or novel is bad. But for that person, I respect their opinion.

Nobody should try to explain a work of art. It’s about feeling. A novel is feeling. A painting is feeling. Someone reads a book, and whatever they feel is their truth. Someone sees a painting, and what they feel is their truth. It doesn’t matter what the painter thought. What matters is what I feel when I look at it.

GH: You emphasize simplicity in your work. Why is that important to you?

HS: I don’t like to make things complicated. Whether in a novel or a movie, it doesn’t matter – I try to keep it as simple as possible. It’s easy to make things complicated. But it’s difficult to make them simple. For me, simplicity is important. I don’t want to make people suffer while trying to understand. I don’t like ‘cholesterol’ in my novels or my movies.

GH: Let’s talk about the films you direct. Before writing your first novel, in fact, you directed films. Is there a connection between being a director and being a writer? Are there similarities or contradictions?

HS: I don’t feel any contradiction. When I write a screenplay or direct a film, I do it with one eye. But when I write a novel, I do it with forty eyes. In a novel, you can unleash your imagination. You can say, ‘I saw two million flies in the sky and the stars. And a huri descended from the heavens.’ Everything is possible. You’re free!

But in cinema? You have just one car, and it’s so difficult and expensive. You need sixty people around you to make a film. The concept is completely different. Sometimes, I have the same idea for a film and a novel, but when I turn it into a film, I must find a new way to tell the same story. Cinema is a scandal because it requires so much money, so many people, so much energy. The biggest difference between cinema and novels? In a novel, you can write and rewrite whenever you want. But in film? You have only one chance. One shot. You can’t say, ‘I don’t like this version. Let’s reshoot.’ It’s impossible. When writing a novel, you don’t have to tell anyone what you’re doing. You write in solitude. And when you’re happy with it, you announce: ‘I’ve written a novel.’

But with a film? Two years before shooting, everyone knows you’re making something. And when the result comes out, if it’s terrible, there’s nothing you can do. This practical difference changes how you see the story.

GH: Are you happier being a writer now?

HS: No, I’m also very happy with cinema. Do you know why? Because – fortunately – I never studied cinema. If I had, I would never have made films. It’s too complicated, too theoretical. Every year in Paris, at least thirty students graduate with PhDs in cinema. But after graduation, they never work in cinema. After the success of my first film, I said: ‘I’m so happy to be an illiterate filmmaker.’ Nexwendewar im. (I’m illiterate.) And because of that, I made good films. I wasn’t afraid.

GH: I’d like to end with this question, something that I kept thinking about while reading The Ashes and re-reading My Father’s Rifle. There are so many personal details about your life, your personality, your family. You even used real names. For me, that’s terrifying. It feels so exposed, so open to the public. How do you feel about that?

HS: Sometimes, I like to provoke. I like to break things. I want to give electroshocks, especially to the Kurds. There’s nothing to be ashamed of.

GH: Did any of the friends you wrote about react negatively when they saw their names in the novel?

HS: Fortunately, my friends don’t read!

Gül Hür is a writer and editor exploring Kurdish studies, literature, and the arts through a lens of storytelling, memory, and cultural expression, with an academic background that includes an MA in History from Istanbul Bilgi University.