Across the Kurdish diaspora, many carry the weight of displacement while working tirelessly, achieving great professional success, and remaining proud of their Kurdish language and heritage. Niga Sirwan Nawroly is one such Kurd. After fleeing from Saddam Hussein’s regime to Iran, she moved to the UK, where she continued her studies, raised her children, and promoted Kurdish language and history. Niga recently sat down with Kurdistan Chronicle to discuss her life and journey.

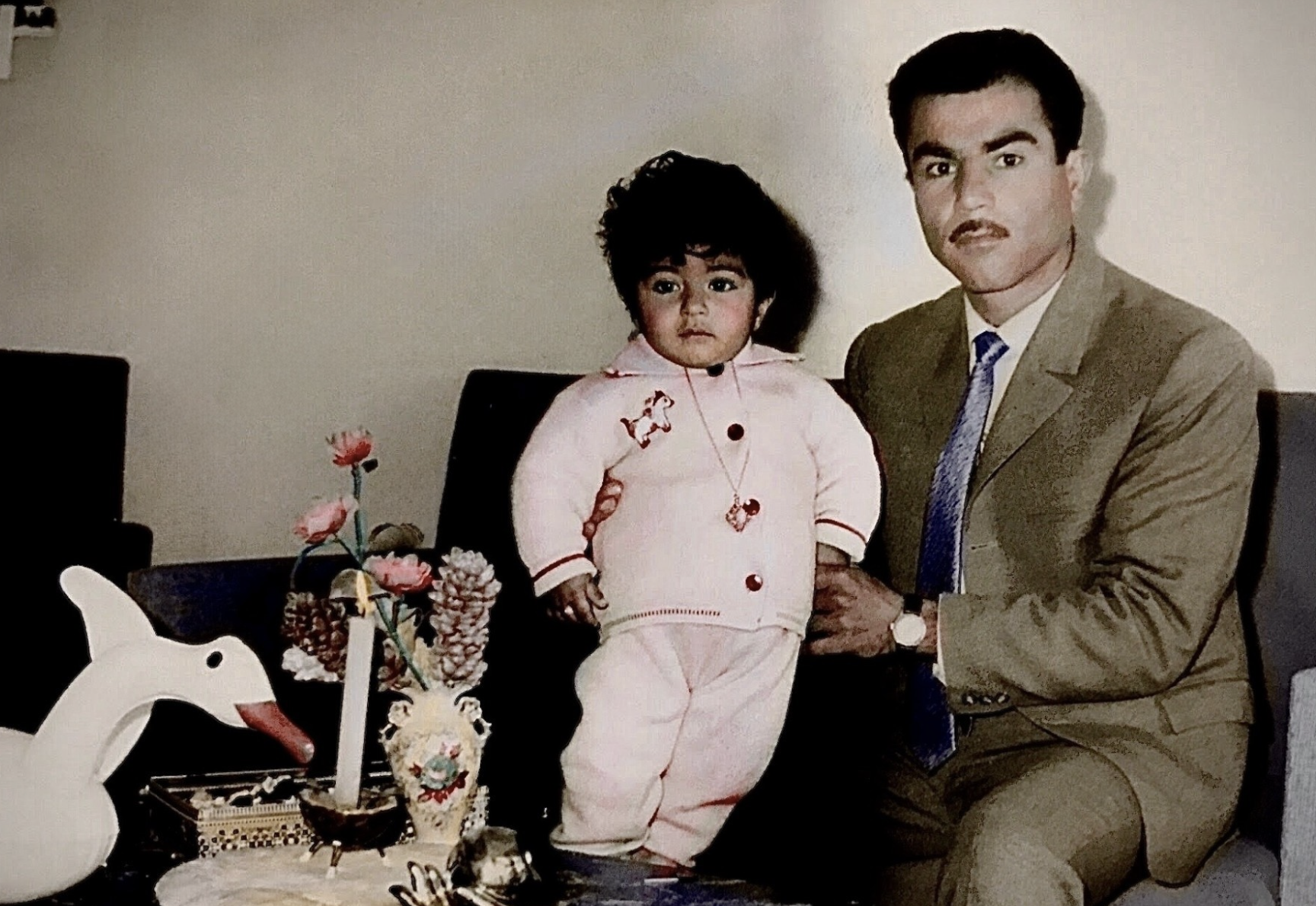

Niga was born in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to a patriotic family, with both her mother and father hailing from distinguished families in the region. Her father, Shahid Mlazim Sirwan Nawroly, was from Halabja and belonged to the Nawroly lineage, known for its commitment to peace among the diverse communities in Kurdistan Region. Her mother, Roonak Mirza Karim, comes from a family with a legacy in art and literature in Sulaymaniyah. Her maternal uncles, the renowned poet Jalal Mirza Karim and the historian and writer Ghafour Mirza Karim, both made significant contributions to philosophy, poetry, and literature.

A peshmerga upbringing

In the late 1960s, Niga’s father studied military science at the University of Baghdad, while her mother worked as a teacher. “My father became a peshmerga and a leader during the Kurdish Revolution. He was known as ‘Shorshi Ayloul’ and went to the mountains,” she stated. “In the 1970s, while my father was still in his twenties, he was elected as the deputy of Hezi Rizgari, a peshmerga group fighting for Kurdistan’s independence. My mother also played a crucial role, teaching children from peshmerga families and supporting the revolution alongside my father.”

Due to her father’s political role, her family faced constant danger from the former Iraqi regime, which brutally targeted the families of peshmerga fighters, imprisoning and torturing them. “My mother was also in her twenties, raising three small children under the age of five. To keep us safe, our extended family helped us relocate to a house in Sulaymaniyah. To avoid detection, the main entrance of the house was disguised to look like a shop. The front was covered with shutters, so that when they were shut, it appeared to be an unused shop rather than a family home,” she told Kurdistan Chronicle.

Niga still remembers those long, frightening nights, when they had to keep the lights off and always stay quiet. Her mother would discretely listen to Kurdistan Radio for any updates on peshmerga activities. She listened carefully to the names of fallen fighters, constantly dreading that she might hear her husband’s name. These were difficult times for many families across the Kurdistan Region.

At the time, Niga was nearly five years old, her sister was two, and her brother was less than one. They stayed in the house in Sulaymaniyah until the Iraqi secret services discovered their hiding place. “My father arranged for us to be taken out of the city and into a village in Eastern Kurdistan (northwestern Iran),” Niga explained. “This was my mother’s only option to keep us safe, even though it meant leaving behind her family, her teaching job, and everything she had ever known. She sacrificed everything.”

Learning in Iran

Their journey to Iran was perilous. “I remember we had to travel at night in an old Jeep to avoid being detected. Even the headlights had to be turned off as we drove along rough, unpaved roads for hours. At one point, we heard gunfire and had to stop suddenly. We were told to jump into a shallow lake, hiding among the bushes in the darkness. I still remember the fear and the cold water as we waited quietly, hoping to remain unseen.”

Eventually, they made it to Paveh, a small town in Iran’s Kermanshah Province where most of the population was Kurdish, allowing them to feel at home and communicate easily.

Most importantly for Niga and her siblings was that their father was able to visit them. “I still remember the first time I saw him after our escape. He looked exhausted, having just come from the front lines. It was always difficult, missing him and constantly fearing he might not return.”

Later, they moved to Karaj, near Tehran, where Niga started school and learned Farsi. Adjusting to her new home was challenging; unlike in Paveh, the people in Karaj were not Kurdish. “My parents did not speak Farsi at first, so as a child, I learned quickly by playing with the neighborhood children,” she recounted. “Soon, I became my family’s translator, handling errands, shopping, doctor visits, and even talking to landlords – all at just five years old.”

This responsibility helped Niga grow more resilient. Despite all these challenges, her father played a crucial role in ensuring that his children never missed out on their education. “He also wanted us to enjoy our new environment, taking us to see different places and encouraging us to learn about Iran’s rich history and culture. Despite everything, he found ways to make life in Iran more than just about survival – it became a time of growth and learning.”

Rebuilding in Kurdistan

After the collapse of the Kurdish Revolution, they returned to Sulaymaniyah under Mustafa Barzani’s orders. “My father was assigned to work undercover as a peshmerga, continuing his fight for Kurdistan’s independence,” she explained.

Niga’s family began rebuilding their lives. She and her siblings returned to school in their hometown, and her mother resumed her teaching career. On the surface, life seemed normal, but in reality, they faced constant challenges. “My father was always under strict surveillance by the Iraqi government, yet he never ceased his work as an undercover peshmerga. He remained dedicated to the cause until the Kurdish uprising in 1991,” she stated.

“Coming from a peshmerga family, we were always fighting for the freedom of Kurdistan. Tragically, this dedication came at a great cost. In 1997, my father was assassinated while serving in the Kurdistan Region Parliament,” she added.

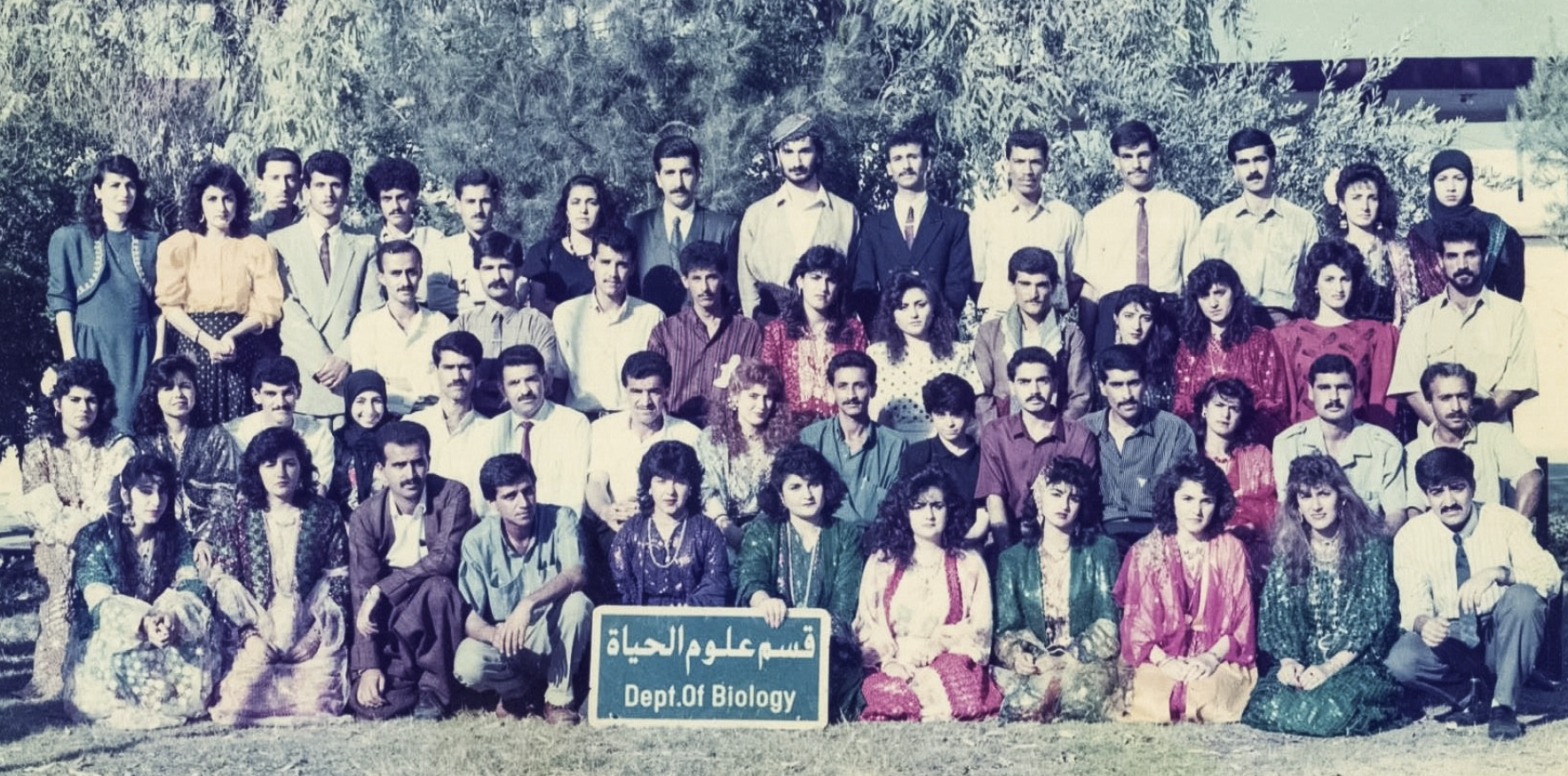

After completing high school in Sulaymaniyah, Niga moved to Erbil to study biology at Salahaddin University and, upon graduation, returned home to work as a teaching assistant at Sulaimani Technical Institute. “It was during this time that I developed a strong interest in hematology, blood disorders, and blood cancers,” she says.

Professional success in the UK

In 1995, Niga moved to the UK to join her husband and pursue a master’s degree at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School, Imperial College London. “I completed my degree with distinction, focusing on the immunology of heart transplantation,” she recalls. She has since dedicated her career to immunology, cancer biology, blood disorders, and diabetes research.

Niga currently resides in London with her husband, Aram, and their two children, Shazo and Dyako. When I asked her how she feels as a stateless Kurd achieving success abroad and how her Kurdish background has influenced her academic and professional journey, she reflected on her upbringing. “I was surrounded by ambitious and successful people – my parents, uncles, and extended family. My parents made sure we had every opportunity to study and succeed, so working hard and achieving was the natural path for me,” she said.

“Being Kurdish is something I take great pride in. It motivates me to push even harder to succeed and challenge the negative portrayal of Kurds in the media. My parents made enormous sacrifices for Kurdistan’s freedom, and their legacy has had a deep impact on my own journey,” she added.

When I inquired about Niga’s long-term goals and career aspirations, she eagerly shared her aim to continue advancing cytometry for use in cell and gene therapy, mentor future scientists, and collaborate with researchers. “My goal is to apply my 25 years of experience to benefit Kurdistan in healthcare, medical research, and academia.”

During her research, she developed a particular interest in flow cytometry, a technology used in biomedical analysis with various applications, such as leukemia and blood cancer diagnosis.

This passion led Niga to her involvement in the London Cytometry Club for eight years, as well as serving as a Committee Member of the Royal Microscopical Society for 12 years. “I have worked as an educator and mentor in cytometry for over 15 years, holding positions at Imperial College London, the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology, Queen Mary University of London, and the Institute of Child Health. Eventually, I transitioned into the biotechnology industry, working as a cytometry specialist for global biotech companies,” she explained.

I was also curious about how individual Kurds living abroad and achieving success in various fields feel about their Kurdish identity and how it has influenced their work. “Being Kurdish is my identity,” Niga immediately responded. “The challenges we faced have taught me resilience and determination. Our history of struggle and perseverance is a constant source of inspiration.”

Mentoring future generations

This drives Niga to support and mentor the next generation of Kurdish scientists, helping to highlight their contributions to the global scientific community. Despite growing up abroad, Niga’s children speak Kurdish fluently. She recognizes the importance of the mother tongue for the new generation, especially those born abroad, and emphasizes the significance of introducing Kurdish culture to them.

“As a family, we have always believed in maintaining our Kurdish identity. This includes preserving the Kurdish language, poetry, music, history, and literature. We emphasize the importance of maintaining our Kurdish culture while also embracing our British identity and being proud of having dual nationality,” Niga explained.

In preserving and promoting Kurdish culture, there are multiple challenges that the Kurdish diaspora faces. One of these is the language barrier; maintaining fluency in Kurdish can be difficult, especially for younger generations who might be more exposed to the language of their new country. “Being proud to speak Kurdish at home is important,” she suggested. “Taking children to Kurdish schools can also be beneficial, providing parents with an educational support system and giving children access to those resources.”

Niga views her contribution to the development of the healthcare system in Kurdistan as a duty. “I mentor and support Kurdish academics and scientists and have done so for the past 27 years,” she stated.

In 2006, Niga and her brothers, Sarkhell and Rawand, established a network connecting universities in Kurdistan with academics from the UK, Europe, and the United States who were willing to collaborate and provide scientific support. They created a website where they published profiles of these academics, including their contact details and areas of expertise. “This initiative was outstanding, as it provided a system to facilitate open communication and collaboration between Kurdistan and academics.”

Lifelong learning

To end the interview, I asked Niga how she balances her passion for science with her hobbies. “Balancing hobbies such as photography and traveling with my main career brings me so much joy. Seeing different places enriches my life with new experiences and perspectives,” she said.

Her passion for science and technology also keeps her intellectually engaged and stimulated. By integrating these interests into her daily routine, she maintains a lifestyle that supports both her professional growth and personal satisfaction.

Moreover, Niga encourages the younger generation in Kurdistan to embrace learning with dedication and curiosity. “I often share the example of my uncle Ghafour Mirza Karim, a historian and writer, who started learning Farsi in his 70s because he wanted to read Farsi books firsthand,” she said.

Niga advises the younger generation to be proud of their Kurdish heritage and stay connected by building and maintaining relationships with people who share their interests and goals. “Collaboration and support from others can open doors to new opportunities and ideas,” she concluded.

Goran Shakhawan is a Kurdish-American journalist and author based in the United States. He has covered news for several Kurdish news outlets and was a former senior correspondent for Kurdistan24 in Erbil and Washington D.C. He has published several books in Kurdish.