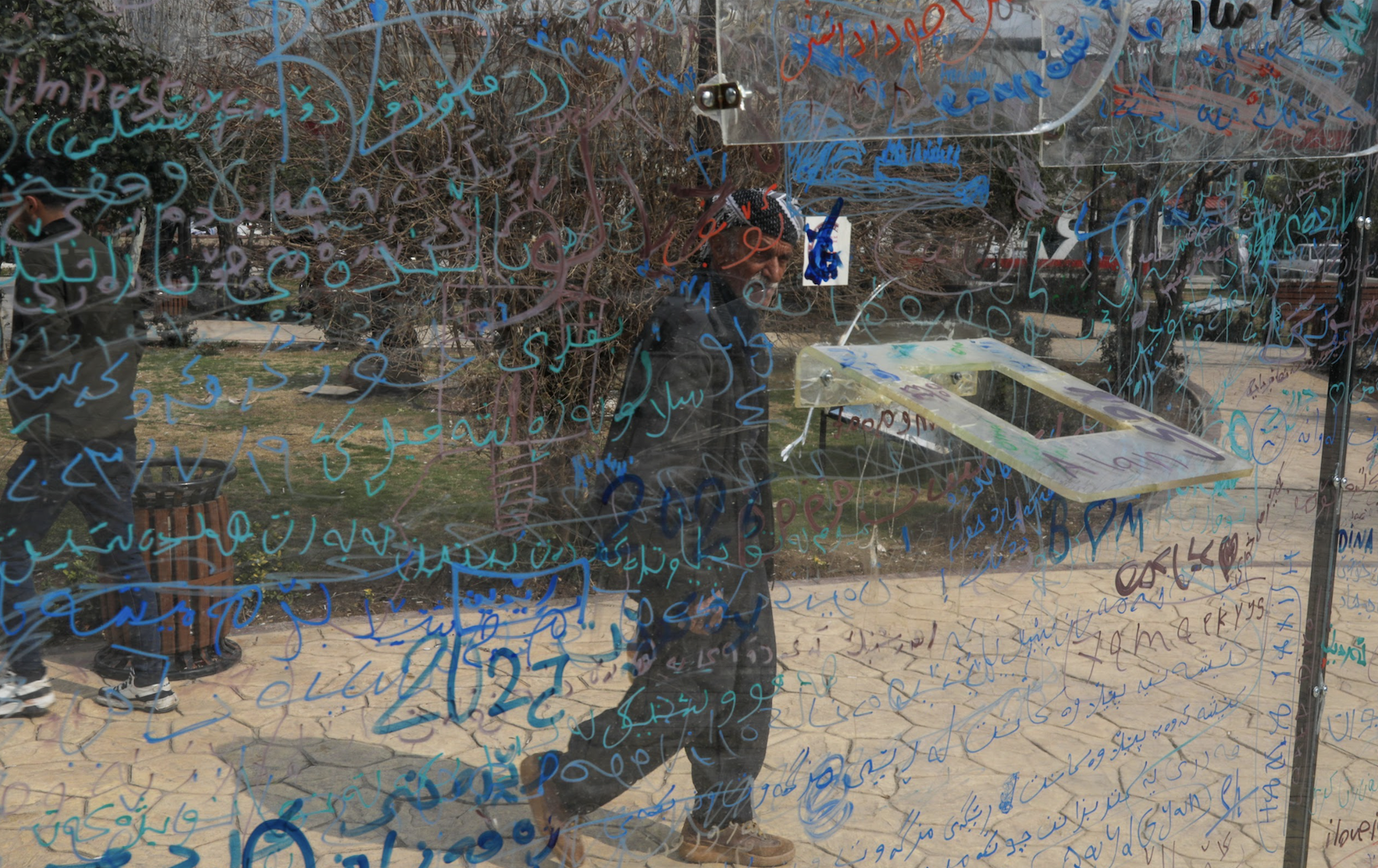

The air hangs heavy with unspoken grief in Ranya Park. Amid the bustle of the town, it offers a rare space for contemplation. But this park is not just a place of rest – it is a memorial.

Dominating the scenery is ‘Being Lost’, a haunting art installation, sponsored by Kurdistan Center for Art and Culture (KCAC), showcasing the faces of Ranya residents who died trying to reach Europe, alongside portraits of their grieving parents who still search for answers. It is a daily reminder of the allure and the peril that lie across distant lands and seas.

Sarkawt Mawloud, 41, sits beside the installation, his gaze fixed on the faces that seem to stare back. Just four days ago, he walked through the park’s gates as a returnee, ending a seven-year stay in the UK. Driven by the hope of a better life for his family, he had left behind a one-year-old son. Now, back on familiar soil, he offers a stark warning: the dream of Europe is often a dangerous illusion.

“I deceived myself with the false promise of life in Europe,” Sarkawt confesses, his voice tinged with regret. “I lived in the UK for seven years and didn’t like it one bit. I was miserable leaving my family behind. I was always looking for a decent job and trying to get residency.”

Years passed in limbo, ultimately ending in disappointment.

He remembers the hope that once propelled across borders: a desperation to provide for his family. Now, as he looks at the faces in the park – young and old lives cut short – his heart aches for those planning the same perilous journey.

“Please, do not be deceived,” he pleads, his voice rising with emotion. “Please don’t put your children’s lives in danger by crossing the sea in overcrowded inflatable boats. Kids don’t understand why you are doing this. They don’t understand the risks.”

The sacrifices, he now sees, were too great.

The mirage of migration

Sarkawt’s experience reflects a stark reality: Europe is becoming increasingly unwelcoming to refugees. “You feel it everywhere you go,” he says, a weariness settling over him. “You’re not welcome. Even if you get citizenship, they still see you as a refugee. You’ll always be a refugee in their eyes.”

His warning comes amid tightening migration policies across the EU. The European Commission is advancing reforms to streamline deportations of failed asylum seekers, including the creation of “return hubs” and a unified approach to returns across member states, policies Sarkawt deems creates unnecessary “hurdles.”

While intended to restore public confidence in migration policies, these measures have drawn sharp criticism from human rights groups such as Amnesty International, which argues that they represent a dangerous erosion of migrant rights.

Sarkawt’s path mirrors that of Bakir Ali, another Kurd lured by the European dream, who returned home and is now dedicated to helping others avoid the same fate.

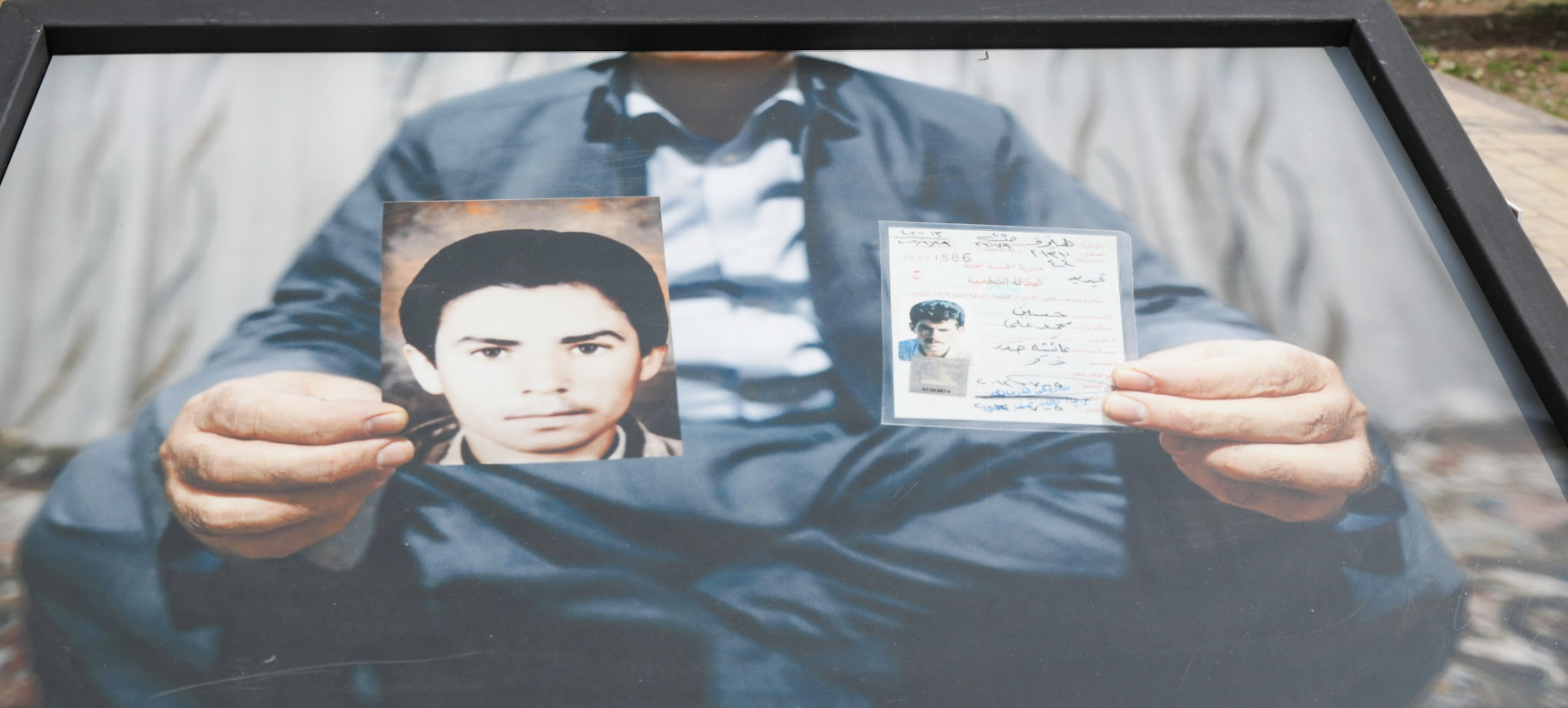

In Ranya, the office of Bakir’s Association of Returned Migrants from Europe to the Kurdistan Region is itself a stark reminder of shattered dreams. The walls are lined with photographs: young men, children, entire families – each face a silent testament to the perilous journeys taken in pursuit of a better life.

“These are the victims,” says Bakir, 51, the association’s director, his voice thick with emotion as he gestures toward the images. “Those who lost their lives trying to reach Europe.”

Each picture bears a name, an age, and a location – Turkiye, Greece, Poland, Hungary – the final, tragic coordinates of their shattered hopes. “Sometimes, when I’m alone here at night, I sit in front of them and I just cry,” Bakir admits, tears welling in his eyes.

He and Sarkawt once shared the same naivete. “We all believed in a mirage,” he would later admit, “the kind that smugglers sell. The promise of wealth and happiness.”

Better to live in one’s own country

Bakir’s association, founded with fellow returnees, works to prevent more tragedies. “Our goal is twofold,” he explains. “To warn people about the dangers of illegal immigration and to help returnees rebuild their lives here in Kurdistan.”

Having lived in Europe, Bakir believes the reality falls far short of the dream sold by smugglers. “People imagine Europe as a paradise, where money grows on trees and life is easy. But the reality is often a life trapped between four walls, a relentless cycle of work and isolation,” he says.

To counter this illusion, his association holds workshops and seminars, showing harrowing videos of refugees packed into overcrowded boats, praying as the waves crash around them.

Bakir’s mission stems from personal tragedy. In the 1990s, facing severe economic hardship, he made the illegal journey to Europe. “I walked for 14 days, from Kurdistan to Iran and then into Turkiye,” he recalls. But tragedy struck at the Turkish-Greek border. “Turkish border guards opened fire. I lost a friend that day.”

After 11 years in Europe, Bakir returned in 2010. The tragedy of his friend’s death never left him. “It became a pain in my heart,” he says. “That pain inspired me to start this association.”

Now, Bakir turns once more to the photographs on the wall. “Look at these beautiful young people,” he says, his voice barely a whisper. “Lost on the route to Europe. So many mothers and fathers are living in agony now, mourning these beautiful souls.”

Like Bakir, Sarkawt visits Ranya Park regularly, standing guard against the dangers of believing in the mirage of Europe. He shakes his head and says, “Don’t believe in the illusion of moving to Europe. It’s better to live in your own country.”

Qassim Khidhir has 15 years of experience in journalism and media development in Iraq. He has contributed to both local and international media outlets.