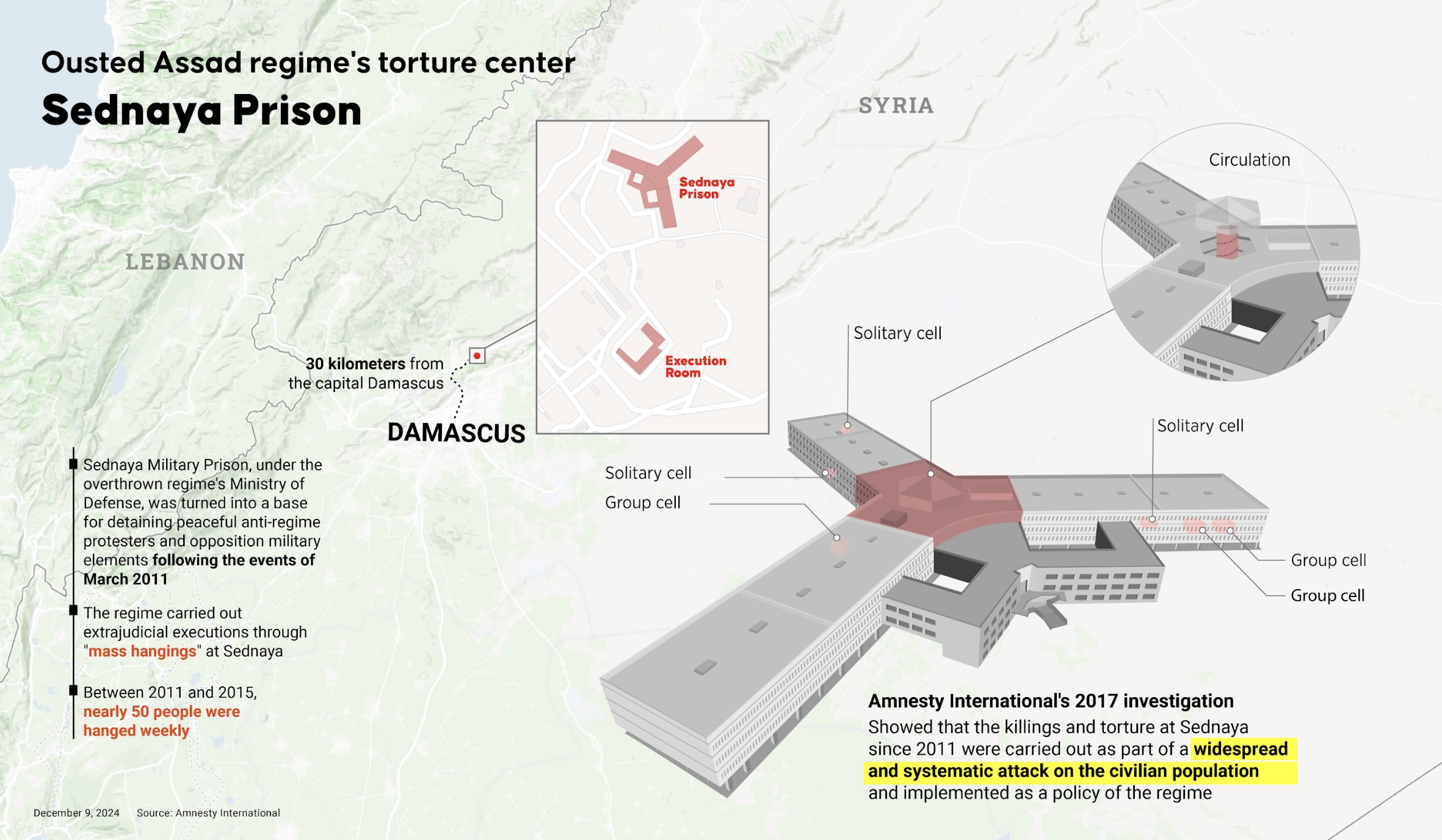

The regime of Bashar al-Assad has fallen, marking the end of a dark era in Syria’s modern history under the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. TV screens broadcast chilling scenes of fighters smashing the locks of the most notorious prison Syria has ever known – Sednaya.

Often referred to as the “human slaughterhouse,” Sednaya held thousands of Syrian citizens from all backgrounds, as well as detainees from neighboring countries. Survivors have recounted horrifying stories about this Ba’athist prison, which was no less brutal than Nazi camps or the infamous prisons of the former Iraqi Ba’ath regime, such as Abu Ghraib Prison.

Early days of the revolution

“When the revolution in Syria broke out in 2011, we mobilized to ensure that the first demonstrations took place in Qamishli, Amuda, or Afrin. We wanted them to start in Kurdish areas due to the Kurds’ deep-seated resentment toward Assad’s regime,” says activist Shibal Ibrahim, who endured months of brutal detention in the infamous Sednaya Prison.

“Even before the revolution, there was immense pressure due to the heavy presence of Syrian security forces in the governorate, including elements dispatched from Damascus to the Kurdish regions of Syria. Regime officials met with various Kurdish figures, tribal leaders, and political parties that played a role in mobilizing the Kurdish street,” he explains, recounting the early days of the Syrian uprising and the involvement of Kurdish youth.

Ibrahim clarifies that the security forces that arrived in the Kurdish areas carried two messages: the first was a veiled threat warning Kurds against organizing protests or taking any action against Assad’s regime, and the second, according to him, was an attempt to appease the Kurds, a tactic the regime often resorted to when feeling threatened.

Having endured harrowing days of torture after his arrest in 2011, the activist shares his account with Kurdistan in Arabic through a series of voice messages detailing the early Kurdish youth movement against the regime. “On March 15, 2011, after the sit-in organized by families of detainees, civil society activists, and artists in Damascus, we began to sense the winds of change. On March 18, the first demonstration erupted in Daraa, and soon, protests started spreading. In Newroz in 2011, the regime attempted to win over the Kurds by sending a security delegation to extend holiday greetings,” he recounts. However, Ibrahim insists that this move was nothing more than “a cheap political ploy by the Assad regime.”

Discussing the early days of the revolution, including the formation of coordination committees – youth groups organizing anti-regime protests – he clarifies: “I wasn’t among the founders of these committees, but on my own initiative, I invited many to join a gathering scheduled for March 25, 2011, to announce the ‘March Coordination Committee.’ Unfortunately, very few attended.”

The former activist and political prisoner adds that from that day forward, he never missed a protest, eventually being assigned the role of General Supervisor of Kurdish Youth Coordination Committees in Qamishli. Syrian Kurds embraced the new movement and integrated it into their cities, aligning with the broader Syrian revolutionary movement. According to Ibrahim, this was due to “the years of suffering under the regime’s oppressive policies toward the Kurds in Syria.”

The arrest

Shibal Ibrahim recalls the circumstances of his arrest due to his activism, describing it as a kidnapping without any legal warrant: “The Air Force Intelligence arrested me in Qamishli on September 22, 2011.”

From Qamishli to al-Hasakah, then to Deir ez-Zor, Mezzeh Airport, the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Bab Tuma (also controlled by Air Force Intelligence), Qaboun Military Police Prison, and finally, Sednaya – Ibrahim endured a nightmarish journey through the hands of the regime’s brutal enforcers.

The treatment was, unsurprisingly, extremely harsh. The torturers “took pleasure in tormenting detainees through every imaginable method... They even competed to see who could inflict the worst forms of torture, proving their loyalty to Assad’s regime.”

“The prison guards had absolute authority to carry out any form of torture,” Ibrahim says. “If a detainee died under their hands, there was no accountability – on the contrary, they were often rewarded.”

Regarding the number of detainees, Ibrahim estimates that “more than a thousand people were arrested daily. The security branches became so overcrowded that there was no space left for the swelling numbers of detainees.”

According to his testimony, which aligns with numerous other accounts, the Assad regime resorted to placing detainees in public spaces such as sports stadiums and even candy factories, giving security forces free rein to act as they pleased.

Crossing from Hell

Crossing from Hell is a narrative documenting the harrowing experience of Kurdish youth activist Shibal Ibrahim. It offers a glimpse into the inhumane and terrifying conditions endured by detainees in Sednaya Prison – conditions the world only became fully revealed after the regime’s fall on December 8 last year.

“I recounted my personal experience in Crossing from Hell to draw the world’s attention, particularly human rights organizations, to the extent of the torture taking place inside these prisons,” he says.

The book was published long after Ibrahim’s release. “I didn’t want to cause the mothers of detainees additional pain by revealing the brutal conditions inside these prisons,” he explains. “However, years later, after the release of the Caesar photos and other evidence, I decided to document my experience in this novel.”

“They never stopped torturing me from the moment of my arrest until my release,” he asserts. He also reveals that General Suhayl al-Hasan, who was then the head of Air Force Intelligence investigations, personally oversaw interrogations. Known as one of the regime’s most ruthless enforcers, al-Hasan was responsible for the Ghouta massacre and has a history of crimes against humanity.

“The Air Force Intelligence branch is like a five-star hotel compared to Sednaya Prison,” he continues with anguish. “People thought I was exaggerating when I described what happens in Sednaya, but after the regime fell and prisoners were freed, the world was shocked by the horrors they witnessed. What people saw on their screens – I lived through it, in all its terror, for a year and a half.”

Jan Dost is a prolific Kurdish poet, writer and translator. He has published several novels and translated a number of Kurdish literary masterpieces.