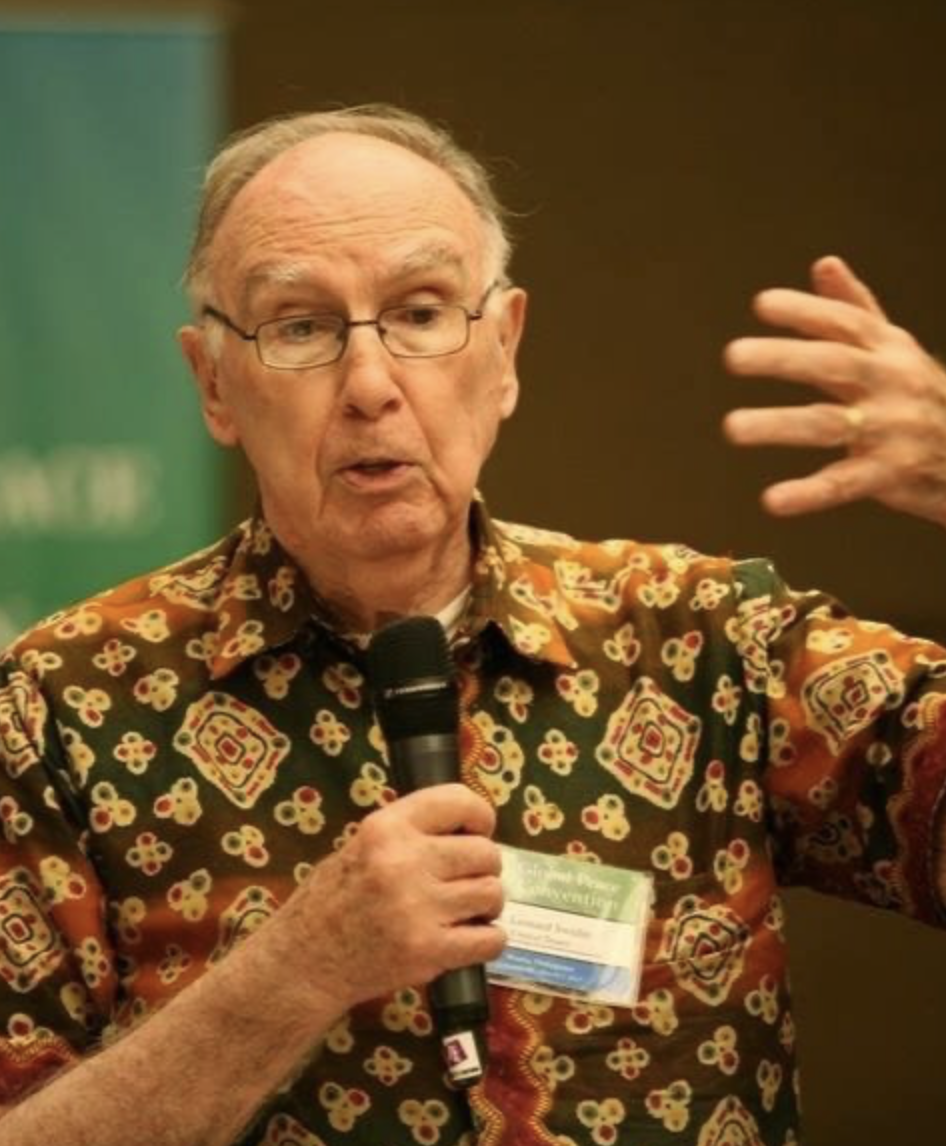

Born in the United States in 1929 to an immigrant family of Ukrainian and Russian origin, Professor Leonard Swidler experienced religious and racial discrimination and oppression throughout his life. Despite this, he channeled his upbringing into a lifelong devotion to interfaith dialogue, seeking for ways to heal the rift between Catholics and Protestants.

Professor Emeritus of Catholic Thought and Interfaith Dialogue at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Swidler recently sat down with Kurdistan Chronicle to discuss a wide range of issues relating to his life’s work, Kurdistan, and the ongoing importance of dialogue. “No one knows everything,” he emphasizes. “Therefore, there is an urgent need for dialogue to expand our knowledge and understanding of life and others.”

A life of the mind, and the heart

Now considered a global theologian, Swidler started his educational journey in a traditional path – engineering – before abandoning after two years of studying philosophy and becoming a Catholic preacher. Thereafter, he completed a master’s degree and decided to specialize in the study of Catholic thought and history at the University of Tubingen and the University of Munich in Germany. He then went on to obtain a doctoral degree in history from the University of Wisconsin in 1961.

In 1966, he became a professor of Catholic thought and interfaith dialogue at Temple and founded a new department concerned with interfaith dialogue. It included scholars of Catholicism, Protestantism, and Islam – including the Palestinian thinker Ismail Raji al-Faruqi (1921-1986), who specialized in comparative religions – and was the first time that a state government in the United States had supported a university in establishing such a department.

The department served as a springboard for Swidler to devote his life to researching ways to heal the rift between Catholics and Protestants. He later expanded this interest into trying to bring religions closer together and spread knowledge about them, nurturing a culture of dialogue and tolerance among people.

These efforts ultimately led Swidler to establish the Dialogue Institute at Temple in 1978, which sought to promote understanding between followers of different religions and of different cultures. Swidler says that the institute was built on the belief that dialogue “is the best way for people to understand each other and the best means to resolve conflicts and problems around the world.”

The Dialogue Institute has since carried its message to many countries across Asia, Europe, and the United States, including but not limited to Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Sudan, Lebanon, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia. Recently, its mission has expanded to the Kurdistan Region via the University of Sulaymaniyah, where Swidler was invited to give lectures at the College of Islamic Sciences during the 2023-2024 academic year.

Breaking down the walls of ignorance and fanaticism

Dialogue is a Greek word that “means thinking and talking together,” Swidler notes. “I found that I wanted to talk to others who have beliefs different from my own so that I could understand their ideas and perceptions and form a better and broader cognitive picture not only about them, but also about the world we live in and even the universe.”

Swidler explains that dialogue “contributes to solving puzzles and mysteries, reducing our fear of the unknown, and communicating with others to find common denominators that allow everyone to live in peace and harmony.”

Regarding the conflict between religions, especially Islam and Christianity, Swidler believes that “the history of more than a thousand years of wars between Christian empires and Islamic countries has created an entrenched hostility between the two parties.”

“This is a natural tendency across religious conflicts, for instance in the Catholic view of the Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther in the 16th century or even between Christian or Islamic sects and groups,” he adds, noting that “the most balanced view of Islam did not appear until the middle of the 20th century, when the activity of the dialogue movement began to rise. Thus, there are now many balanced Christian viewpoints towards Islam.”

Swidler acknowledges that there are Muslims who “deliberately use Islam as a tool for murder and destruction, even though the vast majority of Muslims say that this is incompatible with Islam and that non-Muslims who know nothing about Islam realize that Islam, like all religions, is committed to peace.”

To confront these beliefs, Swidler argues that we need to make greater efforts to learn candidly about Islam. He believes that this can be explained through new and creative means of communication and dialogue, such as blogs and social networks. He also underscores that Christians and non-Muslims have similar responsibilities to introduce their ideas and beliefs, and this will only be achieved through in-depth and open dialogue.

The interfaith scholar also calls on Muslims to loudly and consistently denounce the murder and violence practiced by some in the name of Islam and to consider these acts a betrayal of the faith. He also states that Muslims must “modernize the teaching of Islam to their audiences and focus on their common humanity with non-Muslims, especially since followers of the Christian and Jewish religions believe in one God.”

He believes that, alongside dialogue, openness to followers of other religions and even those who have no religion can enhance understanding through emphasis on the significance of mutual respect and cooperation on both individual and communal levels.

Swidler, whose determination and memory remain firm after years of service and hard work, stresses that “there are more things that unite religions than those that divide them.” Interfaith dialogue, he adds, can contribute to the strengthening of the basic unity of the human family through valuing “equality, the sanctity of the human being, the value of human society, love, self-denial, compassion, strength of spirit, goodness, and advocacy of the poor and oppressed. Finally, it plays a positive role in tearing down the walls of fanaticism and ignorance between Muslims and non-Muslims.”

Interfaith dialogue necessitates a paradigm shift from rhetorical exchanges to a genuine pursuit of knowledge and understanding. Effective dialogue requires in-depth familiarity with diverse religious traditions, fostering mutual comprehension and transformative growth. Moreover, profound religious understanding inherently reveals the intrinsic unity of humanity. This concept resonates with esteemed thinkers, including Sufi philosophers like Manusr al-Hallaj (858-922) and Ibn al-Arabi (1164-1240), who posited the universality of love. Erwin Laszlo (1932), author of the quantum consciousness theory, has also elaborated on this notion, advocating unconditional love towards all humanity.

Kurdistan’s future

Swidler expressed optimism regarding the Kurdistan Region’s future, noting the region’s remarkable progress in various sectors, akin to China’s achievements in recent years despite Western economic pressures. However, he emphasized that Baghdad’s constraints have hindered Kurdistan’s potential.

Reflecting his growing awareness of the challenges that the Kurdistan Region faces and familiarity with the Middle East, Swidler has been invited to establish a Dialogue Institute branch at the University of Sulaymaniyah, which will aim to foster interfaith dialogue among international scholars. The proposal is currently under review by the Kurdistan Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

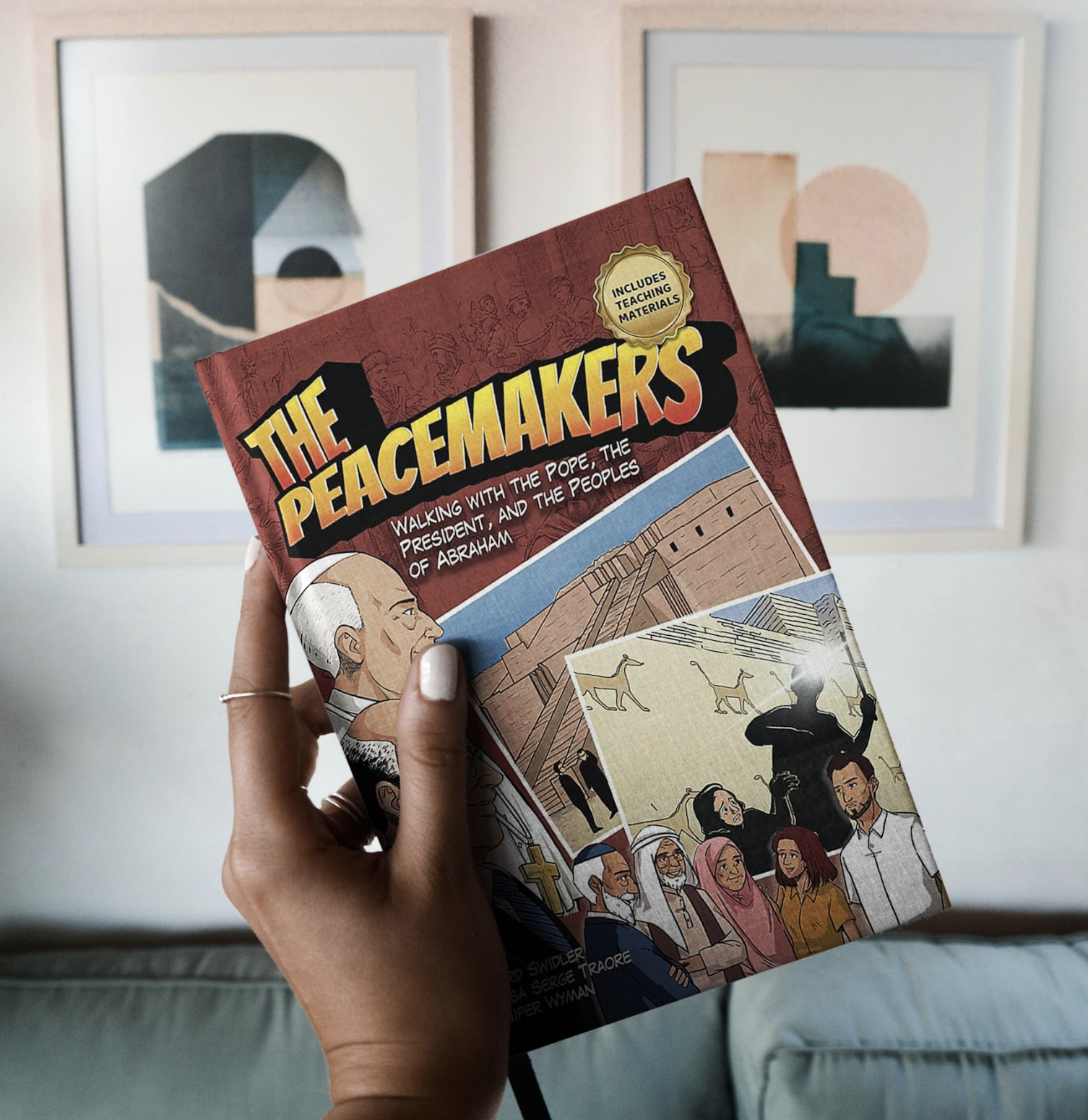

Swidler’s prolific career boasts over 100 books and 200 research papers. Notably, he facilitated the visit of five Halabja chemical bombing survivors to the White House and U.S. Congress in 2013, marking the 25th anniversary of the tragedy. His latest publication, The Peacemakers: Walking with the Pope, the President, and the Peoples of Abraham, explores Pope Francis’ 2021 visit to Iraq.

Basil Al-Khatib is an Iraqi journalist based in Sulaymaniyah, the Kurdistan Region.