Often dubbed “the Kurdish Shakespeare,” the Kurdish poet and philosopher Ehmede Xani (1651-1707) said at the beginning of his famous epic poem Mem u Zin that the work “is a way to express the inner sadness that fills me.” One interpretation of this line is that Xani meant Mem and Zin, two lovers doomed to be disunited, to be symbols of Kurdistan and its Kurdish people.

As those familiar with Kurdish literature know, Xani’s innovative tale is one of the foundational works of Kurdish art, influencing other artists working in a range of media. Mem u Zin is considered the most famous artistic and literary portrayal of Kurdistan’s division as well as the callous history of how others have treated the Kurds.

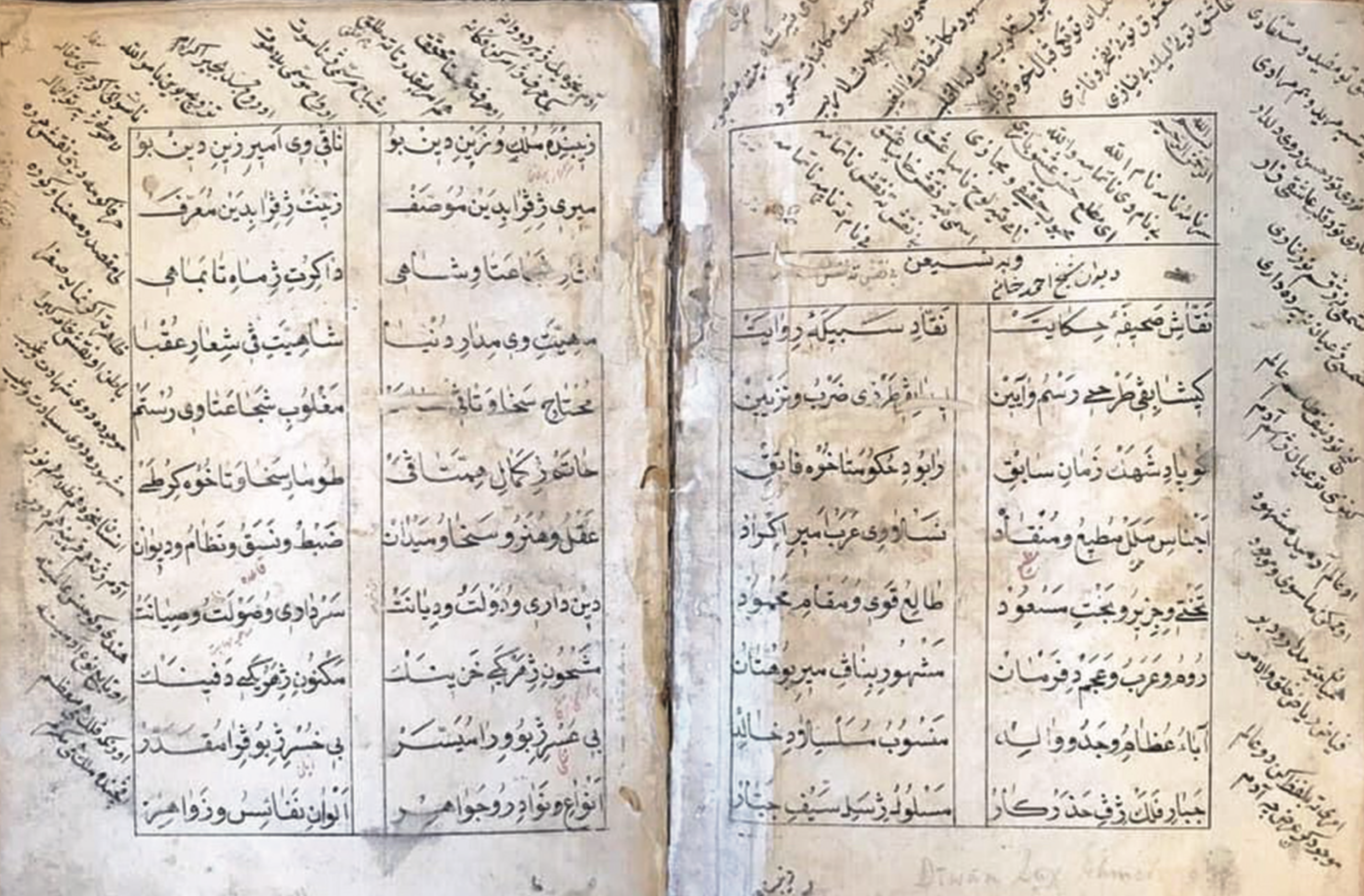

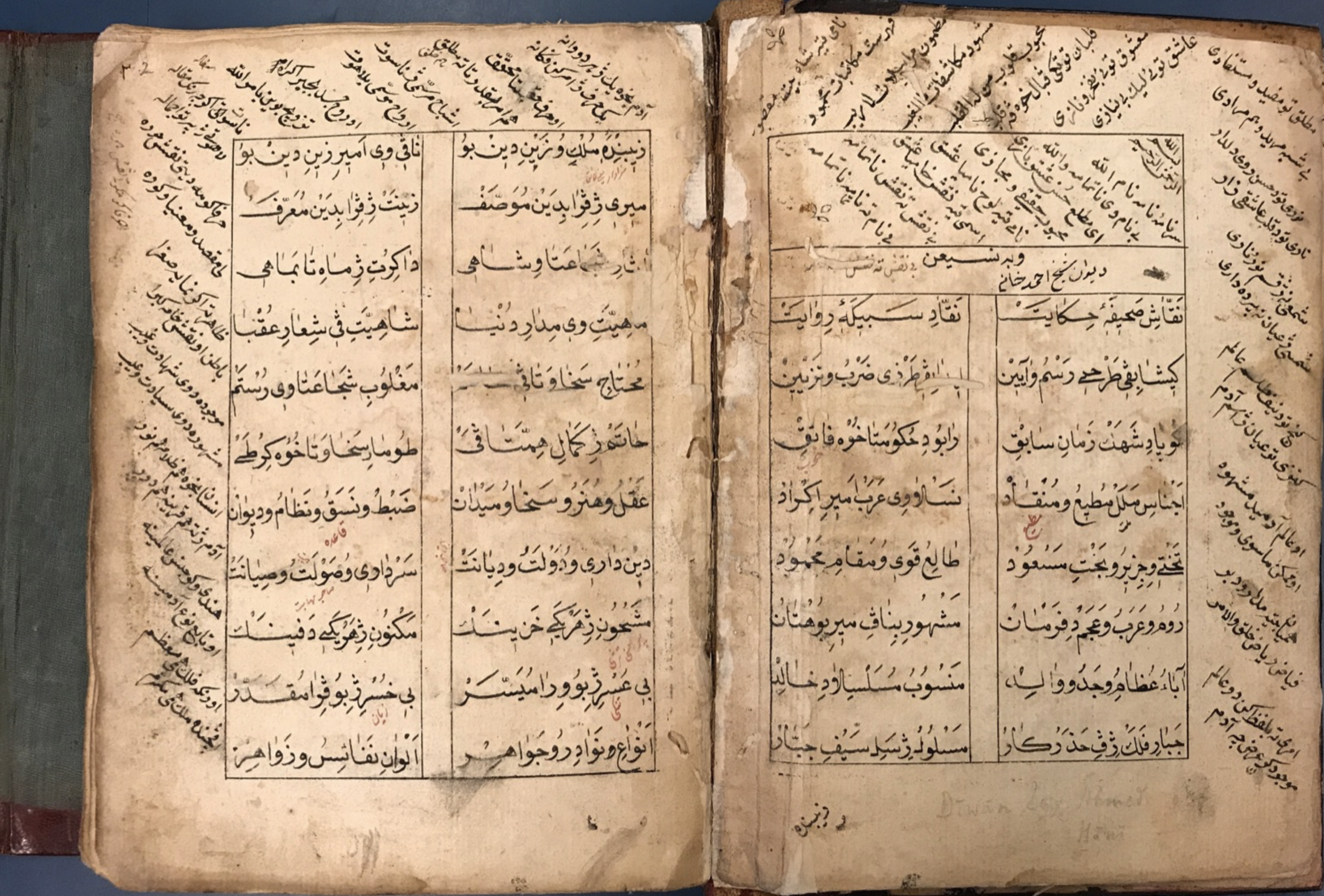

A combination of history, romance, and cultural anthropology, Mem u Zin was published in 1692 and is now considered the Kurdish Romeo and Juliet. It used the theme of national struggle as a backdrop for the story of the two lovers. In addition, Xani brought attention to Kurdish culture when he intentionally chose Newroz, the most significant holiday for the Kurds, as the first date for the two lovers.

To understand Kurdish people, their art, and their literature, it is essential to understand the land they inhabit and their turbulent and devastating history, as both land and history have shaped and divided the Kurds for millennia. A Sumerian clay tablet that dates to the third millennium BC identifies the area that is now Kurdistan as “the land of Karda,” while a people called “Su” were said to live in the regions south of Lake Van. Other Sumerian tablets referred to the people who lived in the land of Karda as Qarduchi and Qurti. Karda/Quardu is etymologically related to the Assyrian term Urartu and the Hebrew term Ararat.

Professor Alessa Lightbourne wrote her latest novel The Kurdish Bike about Kurdish life and culture. She begins with her narrative by underlining the importance of the land of Kurdistan to the life and history of human beings. “A grandiose vibe to the place. You cannot exactly put it into words,” she writes. “Fellows like Gilgamesh, the mythic Akkadian hero king came from here. Patriarchs like Abraham. This is where Alexander triumphed over Darius. A who is who of ancients chiseled themselves into the gritty embrace of history on this very plain.”

Furthermore, Lightbourne says, “in the Shanidar Cave in Kurdistan, which holds the trace of proto humans who first migrated from 65,000 BCE, the earliest forms of domesticated wheat have been found. The first evidence of writing comes from a little to the south. This part of the Fertile Crescent was the breadbasket for ancient Assyria staring around 2,500 BC, and has been home to Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Parthians, Akkadian, Arabs, Ottomans, and more. There is something special about this place, which made people think up agriculture, religion, and writing as we know it.” Indeed, the land nourished these great inventions and breakthroughs.

Land and division

Despite the richness of the region, the Kurdish emirates have never enjoyed a well-established solidarity because of the rugged landscape and because it is landlocked. An orientalist commentator once noted, “if geography helps to define the Kurds, it also helps to divide them. The ranks of jagged peaks, with their walled-in valleys and forbidding chasms, seal the Kurds off from one another as much as from the outside world.”

Empires in the Middle East also contributed to that division. Kurdistan was divided for the first time in 1541, after the Ottomans and the Safavids fought each other in the battle of Chaldiran. As a result of the battle, the Ottomans acquired lands from the Safavids and divided them and the Kurdish people. There were several reasons for this division, but the main one was the invaders’ authoritarian desires, which prompted expansionist policies, greed, and the confiscation of the region’s rich resources.

The two empires also benefitted when Kurdish fighters, famous for their bravery, joined the ranks of the Ottoman and Safavid armies. The bravery of the Kurds was recorded in Greek military leader and philosopher Xenophon’s book, Anabasis. The Kurds, then known as the Carduchi (Kurds), inhabited well-provisioned villages in the mountains north of the Tigris in 401 BC. The Carduchi were enemies of the Persian king as well as Xenophon’s Greek mercenary forces, who entered Kurdish territory and were surprised as battle-hardened hoplites to be met with such hostility. The Carduchi used longbows and slings with deadly accuracy. For the Greeks, the “seven days spent in traversing the country of the Carduchi was one long continuous battle, which cost them more suffering than the whole of their troubles at the hands of the king [of Persia] and Tissaphernes put together.”

Kurdish fighters were appropriated after the battle of Chaldiran and fought in the frequent wars between the Ottomans and Safavids, and against the rising Western powers. Currently, the world’s global powers are treating the Kurds in a similar manner, and so Ehmede Xani’s masterpiece still mirrors reality more than three centuries later.

Chiman Salih a Kurdish legal consultant, writer and journalist.