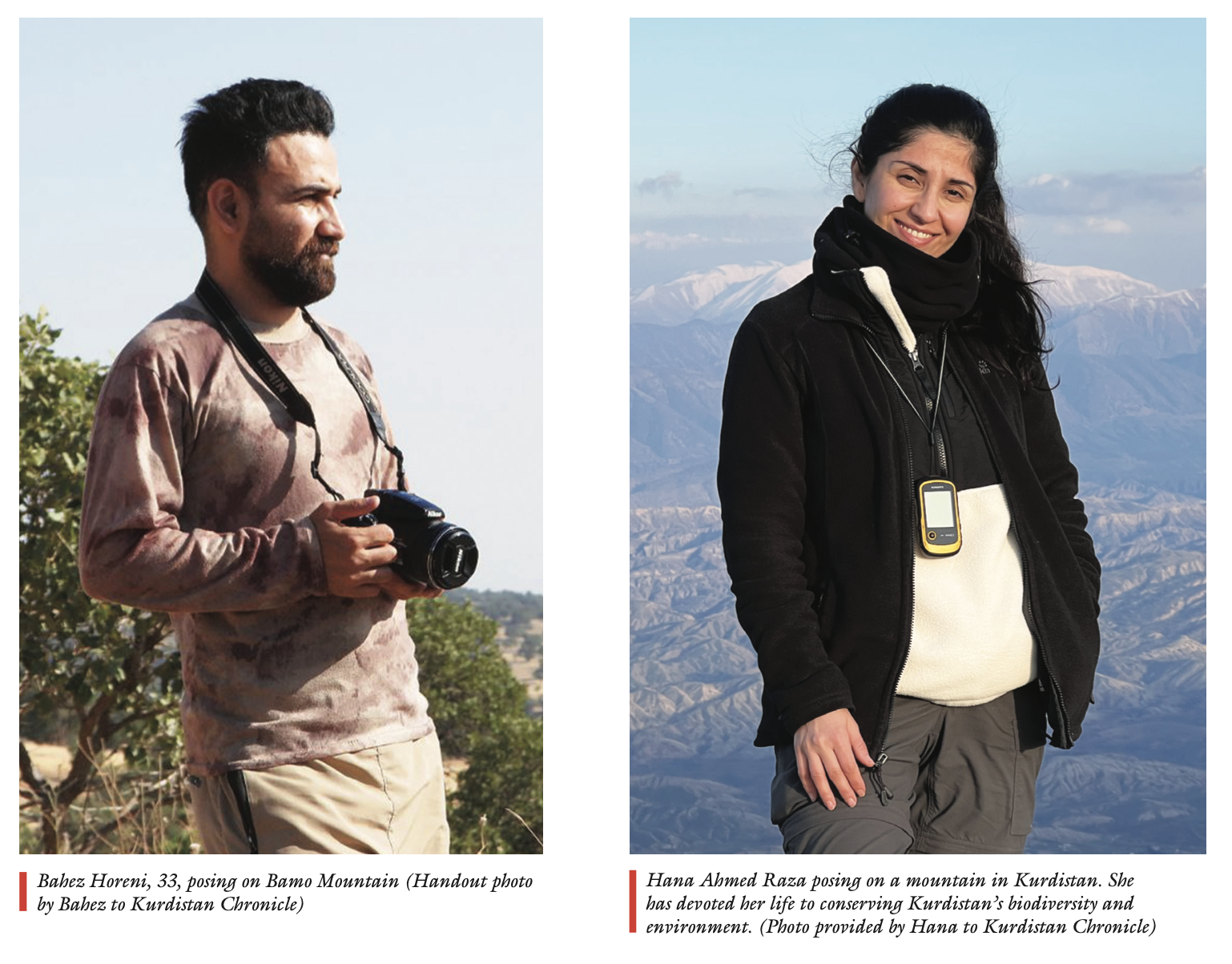

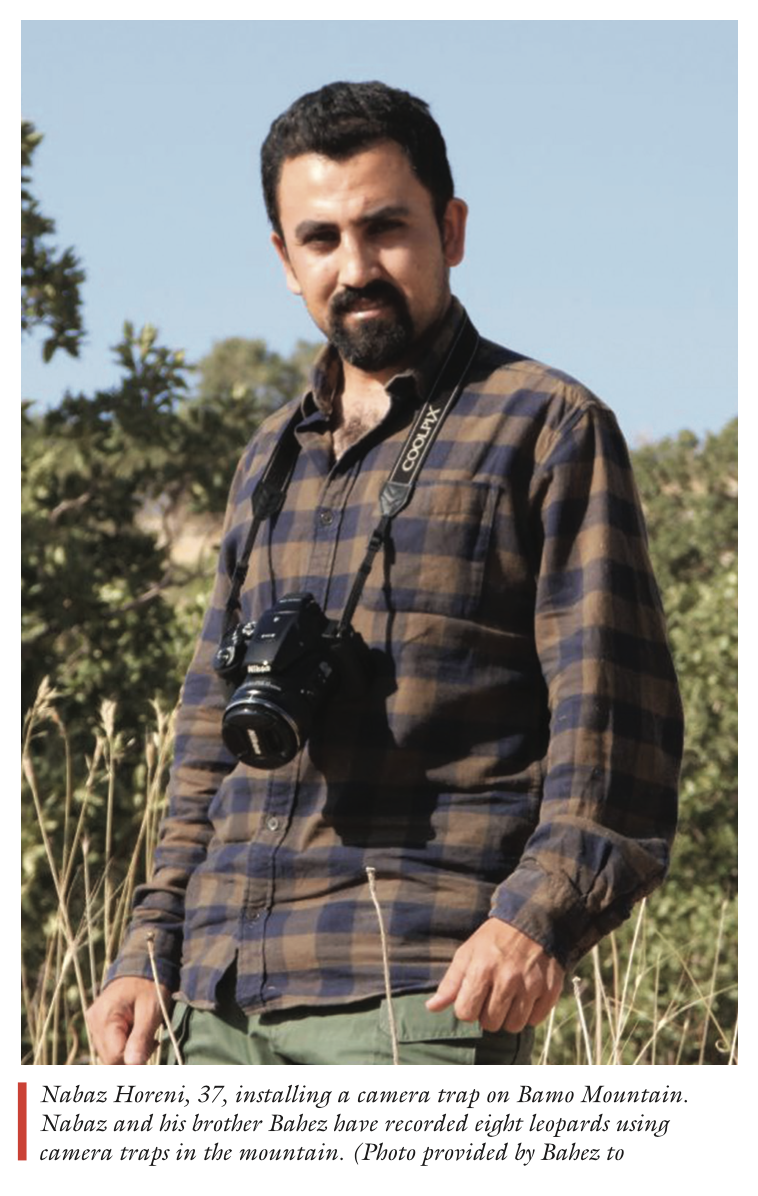

Brothers Nabaz Horeni and Bahez Horeni live in the village of Horen in the Sulaymaniyah Governorate of the Kurdistan Region. Located on the slopes of Bamo Mountain within the Zagros Mountain range, this area is a suitable habitat for wild mammals. Both brothers have a deep love for the nature that surrounds them and have dedicated themselves to protecting the wildlife of Bamo Mountain, particularly its leopards.

The brothers have so far recorded eight leopards using camera traps and were the first in the Kurdistan Region to photograph a leopard family. They were also the first in Kurdistan and Iraq to record footage of a female leopard.

“It was January 6, 2020, when we saw the footage. We hugged each other,” Nabaz recalls.

They decided to name her Kurdistan. It was the first time a leopard had been caught on camera in Bamo Mountain; previously, there had only been word-of-mouth sightings of leopards or documentation of their tracks.

“Since we beginning to document her in 2022, Kurdistan has given birth twice,” Bahez recounts. In the first year, she gave birth to and successfully raised two cubs, one male and one female, whom the brothers named Hiwa and Nishtiman, Kurdish for “hope” and “homeland,” respectively.

Natural challenges

Bahez and Nabaz have spent their entire lives surrounded by the nature of Kurdistan. From a young age, they enjoyed hiking and taking photos and videos of their natural surroundings and its wildlife. Over time, they became aware of the suffering of the wild animals and birds. They began speaking to poachers, urging them not to hunt. As summers on Bamo Mountain became hotter – and rainfall became scarce – they started cleaning wells to ensure that the animals and birds had enough water. When those wells dried up as a result of climate change, they began creating man-made wells.

“We used to have only two hot months in the summer in our village, but now we have four months of hot weather,” Bahez says.

The leopards in Kurdistan’s mountains are internationally known as Persian leopards. Historically, Persian leopards have always lived in the Zagros Mountains, which extend through Iran, the Kurdistan Region, and southeastern Turkey, primarily in areas inhabited by Kurdish people.

In Kurdistan, the Persian leopard is simply called “leopard” (plng in Kurdish). However, Bahez and Nabaz are advocating for renaming it plngi zagros, or “Zagros leopard.”

“By adding Zagros, we want to win the hearts of the people of Kurdistan, so that they might love and protect this majestic animal. Kurdish people have a deep love for Kurdistan’s mountains,” Bahez explains.

This love of Kurdistan’s mountains also prompted Hana Ahmed Raza to devote her life to conserving biodiversity in Kurdistan and beyond. After earning a biology degree from Sulaymaniyah University, Hana joined Nature Iraq – a non-governmental organization in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region that is accredited by the UN Environmental Program – and began collecting data on wild mammals throughout Kurdistan. When she asked people about leopards, they frequently stated that they had not been seen since the 1980s. Despite this, Hana was certain that leopards were still roaming the mountains of Kurdistan.

“I told myself, there is a strong bond between hunter and prey. Since there are wild goats in Kurdistan, I believed there must still be leopards in the mountains,” Hana recounts.

In 2011, for the first time in the history of the Kurdistan Region and Iraq, Hana recorded a leopard, a male, on a camera trap in Qaradagh Mountain, also in Sulaymaniyah Governorate. This picture became the first and only hard evidence of the existence of leopards in Iraq. Previously, there were only unconfirmed written references in literature, which were not enough to prove their presence.

This 2011 discovery motivated Hana to dedicate her life further to protecting the last leopards of Kurdistan. Later, she went to Newcastle University in the UK to study ecology and wildlife.

Poachers threaten Kurdistan’s wildlife

Hana, Nabaz, and Bahez have sounded the alarm: poachers pose the gravest threat to wildlife in the Kurdistan Region, surpassing even climate change and landmines.

“Sadly, Kurdistan has a large number of poachers who are destroying our region’s beauty and wildlife,” Nabaz says.

The conservationist mentioned that the negative impact of poaching involves more than just the killing of animals. Poachers disrupt the ecosystem by killing animals that leopards prey on, like wild goats and porcupines, leaving leopards hungry and forcing them to migrate. Additionally, they steal young animals, like brown bear cubs, and sell them to wealthy people, as happened in a well-publicized case in Duhok Governorate.

Meanwhile, Hana criticizes the media’s role in endangering wildlife. ”Media often portray wild animals like leopards, bears, and boars as dangerous beasts by publishing fake, unverified information about attacks on villagers or livestock,” she says.

“There isn’t a single confirmed case of a leopard attacking a person or domesticated animals in Kurdistan,” Hana emphasizes.

Protecting wildlife has not been easy for Nabaz, Bahez, and Hana. They have faced opposition from poachers who see them as adversaries.

“It’s not our fault,” Nabaz argues. “Poaching goes against the law, religion, and basic humanity. It also harms nature.”

“Maybe it’s divine intervention,” he adds hopefully. ”Perhaps these animals are finally receiving God’s mercy through our passion to protect them.”

Their efforts to curtail poachers have not been entirely fruitless. Some poachers have been convinced to abandon the practice. Bahez shares that some feel ashamed after seeing young people dedicating their lives to protecting wildlife. ”They realize they can’t hide from our camera traps, even if they evade us,” Bahez says. He also mentions that 15 of their camera traps were stolen in just one year.

Regarding landmines, Nabaz offers a surprising perspective. He believes that landmines, especially those along the Iraq-Iran border, have created a haven for wildlife. Poachers are deterred by the danger, and according to their data, landmines have claimed very few animal lives since the 1990s.“We’ve observed a higher concentration of wildlife in areas with landmines,” Nabaz concludes.

What needs to be done

Hana highlights that not only are humans causing problems and threatening wildlife, but there is also a shortage of people working in conservation. She has called on the government and international community to support and encourage those aspiring to become conservationists. Moreover, she urges the government to employ more environmental police and station them in the mountains to protect wildlife from poachers.

“Our aim is to change the image of Kurdistan and Iraq, showing the world that it has protected national parks and beautiful nature,” Hana says.

In 2022, Hana established Leopards Beyond Borders, a non-profit organization in the Kurdistan Region. Nabaz and Bahez are members. These three conservationists are seeking enough support to develop and implement three key projects. First, they aim to designate Bamo Mountain as a community conservation area, supporting the local community in protecting their natural surroundings and wildlife. Second, they want to make Qaradagh a nature reserve. Third, they plan to protect the brown bears in Duhok Governorate.

Their goal is to protect the last leopards of Kurdistan, ensuring that they do not become extinct like some animals that once lived in the region, such as the brown bears in Bamo Mountain.

They also urged the Kurdistan Regional Government and the world community to put pressure on the Iraqi government and Turkey to halt the building of fences along Iraqi, Iranian, and Turkish borders. “These fences will harm wildlife since animals will no longer be able to easily cross borders, and will eventually become extinct. I hope the Iraqi government stops building the fence along the Iranian border,” Hana stated.

The barbed wire fence was recently commissioned by the Iraqi federal government as part of the security agreement with Iran that aims to address security concerns raised by Tehran.

Qassim Khidhir has 15 years of experience in journalism and media development in Iraq. He has contributed to both local and international media outlets.