The Zagros Mountain Trail (ZMT) is a 215-kilometer-long route that runs west to east though the mountains of the Kurdistan Region. The project joins together pre-existing pathways, many of which have been used for hundreds of years by the communities who live there. The ambition of the ZMT is to reimagine these traditional paths as a modern-day cultural route that can be enjoyed by both local and international walkers. Those who travel on the trail meet with guides from each area and can spend evenings in village homes. Through those interactions, and the striking sights and scenery, they begin to learn the story of Kurdistan, as told via a journey on foot.

The ZMT concept has been a work-in-progress since 2016, but has only recently opened to the public. At this point, all visitors are encouraged to walk with local guides so that they contribute to the economy of the areas they pass through. Additionally, with every journey on the path led by someone from the community, the project will always belong to those who live on the trail.

Every visitor to the ZMT is equally important and receives the same hospitality and welcome, regardless of where they are from. Sometimes, however, there are those for whom the visit holds an extra layer of meaning. At the end of May 2024, the U.S. Consul General in Erbil Mark Stroh, several of his staff, and others made the journey through the first stage of the ZMT: walking between the villages of Shush and Gundik. For those associated with the project, visits like this recognize the values and goals of the initiative, and are an opportunity to showcase the elements that make the region so special to a new and different demographic.

Breakfast first

Consul General Stroh and his team arrived at Shush early on a Tuesday morning. His first stop was the home of the village mukhtar Nader Mustafa, the head of the local government, whose family had prepared breakfast for the entourage. It was almost certainly the largest single group to visit this part of the ZMT, but the fifty or so guests were presented with a generous spread of olives, cheese, eggs, freshly baked bread, fruit from the trees behind the house, and an array of honey and jam. When I first started walking in Kurdistan, in 2016, I was told by a village host one morning that any journey on foot is only as successful as the breakfast that precedes it, and I am often reminded how true that is.

As the route leaves Shush it passes by a graveyard with simple upright stones that mark the resting places of one-time Jewish and Christian residents of the village. The Jewish heritage is particularly prominent, and just a few hundred meters along the trail is a recently renovated synagogue dedicated to the Prophet Ezekiel. It is hidden from view at first, with its stone roof covered by grass so that it blends into the hillside, but from below the exterior and low doorway become clear. By some estimates the initial structure of the synagogue was first built 700 years ago, and it remained in use until 1948. The recent rehabilitation of the site was catalyzed by a visit from a previous U.S. Consul General in 2020.

Close by is a stone arch over a natural spring, which Mustafa also attributes to the Jewish community. “Shush was always known for its diversity,” he told the Consul General. “We’re proud that so many different people have lived side by side here.”

Safe, beautiful, and accessible

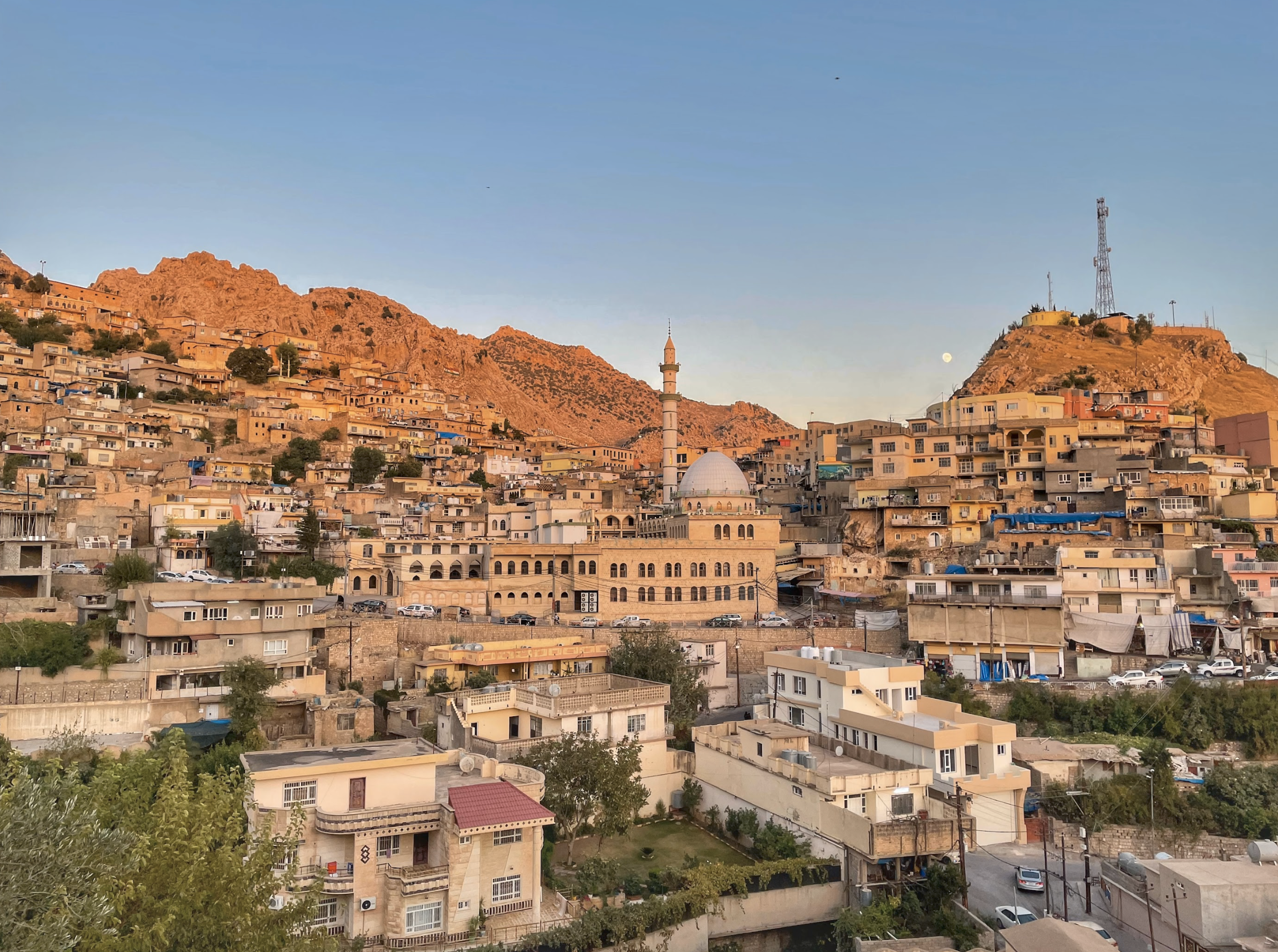

The group walked for a few hours along the shepherds’ tracks that wind out of Shush and along a small valley bounded on one side by high, craggy limestone and on the other by a lower, sharper ridge, with seams of rust and golden soil shining through. These hills are the final barrier before the great plains begin beyond, stretching out toward Mosul and the south.

As we moved, small groups split off to walk together and talk: American diplomats and members of the local community; outdoor tourism advocates and English language teachers. This is the beauty of a trail – it connects travelers to the heritage of the location, but also makes space for spontaneous conversations, and brings together people that might otherwise rarely get a chance to meet. Omer Chomani, owner and founder of tourism company VIKurdistan who helped facilitate the walk, said that this is one of his favorite thing about tourism: watching people have new experiences together.

The route of the trail descends from a high point towards the village of Gundik, nestled around a series of springs that feed bright, bountiful orchards. There, the group stopped one last time at the remains of the Mar Odisho monastery. Its glory has faded, but the 400-year old walls still stand, and the rooms suggest what it might have looked like in the past. On the opposite hillside is a large cave where reliefs carved into the rock date to around 3,000 BC, making them some of the oldest and most important in the region. Like so many sites here, much remains unknown, awaiting further exploration.

“I was really stunned by the beauty of the landscape along the ZMT,” said Consul General Stroh in Gundik, where his journey finished. He was deeply impressed by the kindness and generosity of spirit of the locals, he added. “We hope it encourages more people from Iraq and around the world to visit, and to help develop the local economy.”

Miran Dizayee, one of the key figures in the founding of the ZMT, explained that events like this are important because they help show others that the trail is safe, beautiful, and accessible, and because the attention builds civic pride to those living along its route. Mustafa summed it up, saying “our homes are always open to everyone. I hope this is one of many trips where people from all over the world come to experience the beauty of Kurdistan.”

Leon McCarron is a writer, broadcaster, and hiking trail designer from Northern Ireland. He authored “Wounded Tigris: A River Journey through the Cradle of Civilisation" and has traveled over 50,000 km by human power in the past decade.