This article is part of a critical study about the poet’s works.

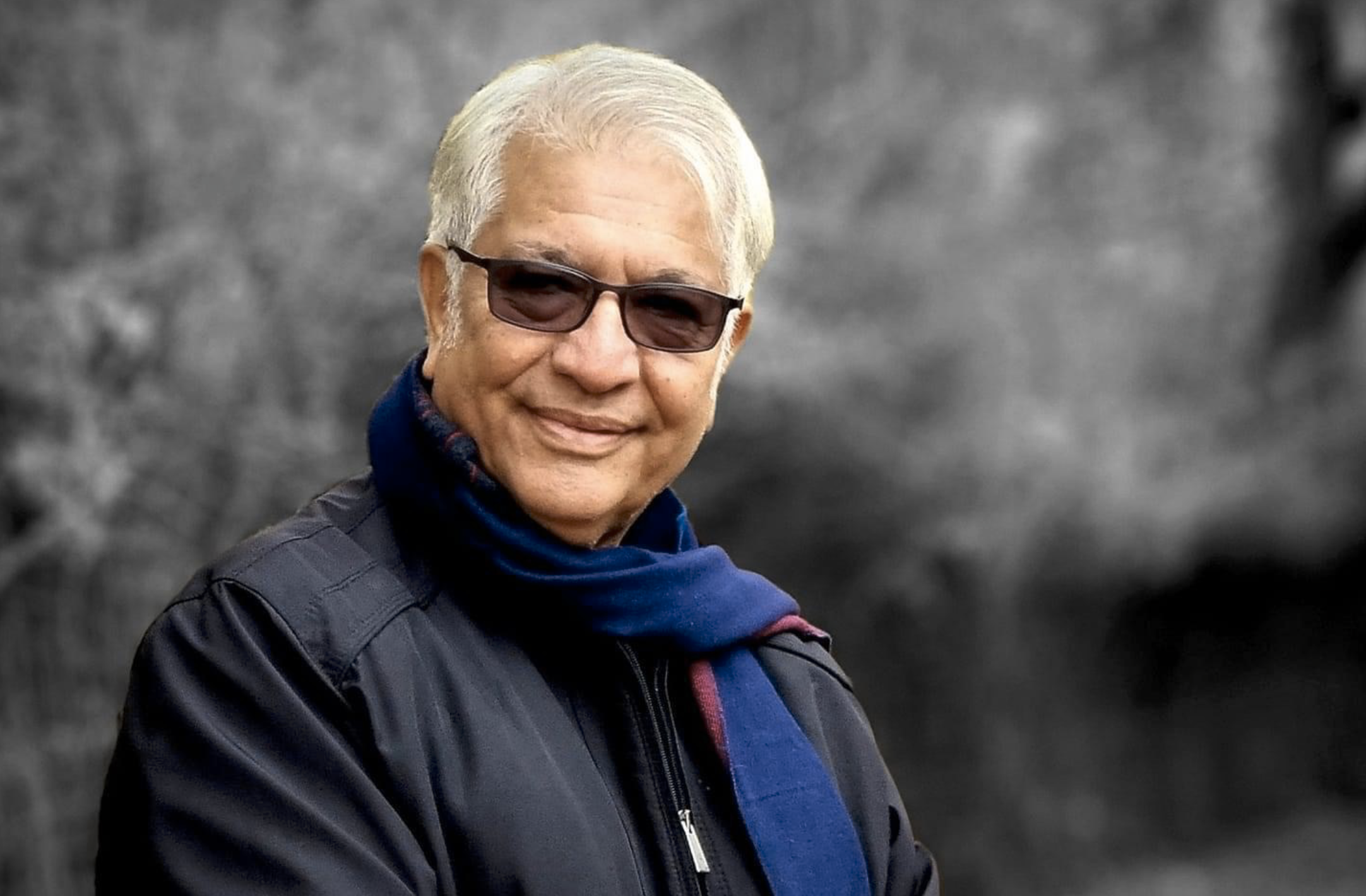

Born in 1953, Qubadi Jalizada is one of the most prominent and distinguished poets in the contemporary Kurdish literary scene in the Kurdistan Region. Throughout his career he has successfully created a modern poetry school and gained recognition as a towering figure in Kurdish literature who is admired by thousands of fans.

Jalizada published his first poem in the monthly Erbil Council Magazine in 1973 while he was a student at Baghdad University College of Law. Since then, he has published 16 collections of his poetry. The poet’s 45 years of experience in writing poetry can be classified into various phases, according to the form, language, and style of the poems.

The evolution of a poet

The poems of the 1988 collection A White Bearded Pen can be considered the poet’s first steps into the literary world. Jalizada shows his poetic talent in composing profound verses; however, the influence of two great Kurdish poets is clear in his work. He is much affected by the expressions of the beauty of nature used by Abdullah Goran (1904-1962) and is trying to imitate the pure and effective language used by the Kurdish famous poet Hemin Mokuryani (1921-1986).

In 1988, at the end of the Iraq-Iran War, the Iraqi army launched a brutal and aggressive attack on Southern Kurdistan (what is now the Kurdistan Region of Iraq). Approximately 182,000 civilians were killed and about 4,000 villages and towns were demolished. The poems of The Black Fog, a collection published in 1990, express the cries, protests, and wounds of these innocent victims. The poet did his best to record the oppression and tyranny of the genocidal attacks and to channel the screams of the persecuted women of his country. During this phase the poet sought a new style of language for his verses.

Jalizada’s next phase of work echoes perhaps his loudest narrative voice. In these poems, the poet’s language is sharpened with deep and influential lexical, idiomatic and cultural terms. Here we see his rebellion against the expired traditional concepts, beliefs, and customs of his society. These cutting, rebellious, and secular poems pushed several religious clerks and preachers to insult him during their khutbahs (Friday sermons at mosques). Jalizada was even brought to court by the accusation that he was an atheist propagandizing against God, though in fact his only sin was calling for serious and practical progress for the freedom of women. Examples of this stage of the poet’s work can be found in the following collections: The Heaven’s Scaffolds (1997), Always Face to Face with God, Always Drunk (2001), The Martyr Walks Alone (2005), and The Sun in the Broken Glass (2006).

Next, Jalizada began expanding into new thematic territory. Hama Saeed Hassan, a Kurdish critic, describes Jalizada as the king of Kurdish erotic poems. Speaking frankly, one can trace the poet’s excursions into this topic from the very beginning of his career. The characteristics of Jalizada’s erotic poems include a soft, magical, and imaginative language that he uses to discover and explore the erotic world, a field that had never been explored by other Kurdish poets before. The images, composition, and forms he uses are truly unique. The poems of Van Erotic (2007) and The Snow’s Bras are Full of Starlings (2010) are the best examples of this phase.

After drinking deeply from the wells of experience and timeless wisdom, Jalizada has matured as a poet and assumed a cosmopolitan approach, through which he uses poetry as a new means for dialogue in our networked world. His collection Qubad’s Hiaku Poems (2017) best exemplifies this approach, while his latest work explores the challenges and limits of creating universal views in a global age. Today, Jalizada is writing his verses in the Kurdish language, but he considers himself an international poet, engaged in conversation with everyone and everywhere on this earth.

Becoming an anti-war poet

In his 1940 letter “To Every Briton,” Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) said, “I appeal for cessation of hostilities, not because you are too exhausted to fight, but because war is bad in essence.”

Jalizada may be one of the few poets in the Middle East who comprehensively understands the hidden symbols of Gandhi’s expression, not only because he is a sensitive poet but because he himself is one of the victims of the seemingly endless fighting and wars in his region.

During the 64 years of Jalizad’s life, the fighter jets have flown overhead constantly, the guns have not been silenced for a single day. The poet lived jumping from war to war; the Kurds fighting the Iraqi, Turkish, French, and Syrian regimes, the Iran-Iraq War, Arab-Israeli wars, the Gulf Wars…the list goes on. The bloody turmoil of the Middle East and of his homeland, Kurdistan, has taught him that war is the most destructive means to deprive us from our humanity and that man has never invented a tool worse than war.

The poet rebukes those who invade his homeland and glorifies the martyrs, but never encourages murdering and destruction.

The style and technique the poet employs to condemn conflict aims to display the harmful inheritance and outcomes of war and to manifest his appeal to consolidate human friendship everywhere.

The poem “Ceasefire” is decorated with manifold poetic images and artful sketches to draw our attention to war’s experiences and effects. Jalizada paints the aftermath so effectively and persuasively that the reader feels ashamed of and scorns all weapons of war.

Ceasefire

The fighting has stopped…

Now, to what avil,

When the moon has lost one of her breasts to it?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what hope does it offer,

When the snow’s lips are stained with blood?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what does dancing mean,

When the butterflies were blocked

From entering the garden?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what use are flowers,

When the parks are full of

Handicapped people and widows?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what music is there to play,

When the nightingale is dressed in black forever?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what value does glory have,

When the martyr is depressed and vagrant?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what is life,

When the gravedigger

Has yet to lay down the pickaxe?

The fighting has stopped…

Now, what kind of peace is it,

When war is always going on?

The dominant themes and topics in Jalizada’s poetry are his ideal of love for women and humanity, his enthusiasm for freedom, and his admiration of nature. His way of depicting nature and the inner life of human beings is unique within Kurdish literature. Here and through other aspects, Jalizada reveals a kinship with many well-known Eastern poets. He remains faithful to his personal vision of reality and the whole universe can be seen in his unique style, expression, and imagery. Today he is known as the king of Kurdish erotic poetry and possesses an unmistakable poetic language all his own.

Fazil Shawro is a Kurdish poet and educator. He has published several literary works. He is a member of the Kurdish Writers Union and has received multiple awards for his contributions to literature and education.