“One misses their mother tongue. We, the Kurds, are basically in exile in our homeland. Not only our land but also our language has been taken away from us. In Turkey, where nearly 20 million Kurds live, the number of people who can read and write in Kurdish can only be counted in the thousands. This shame is not ours, but the state’s.”

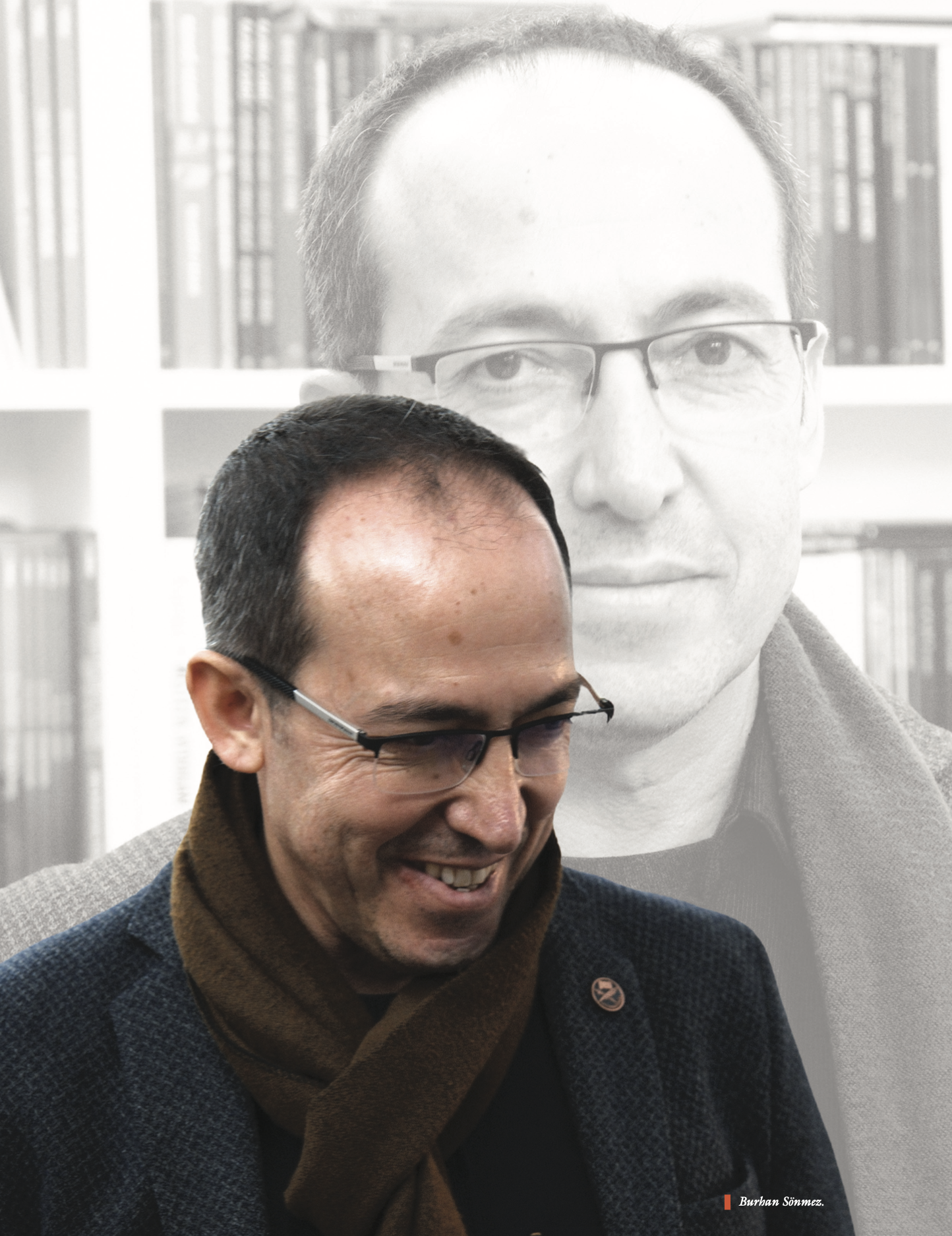

Burhan Sonmez, a Kurdish writer from the municipality of Haymana in Ankara, Turkey, was recently elected President of PEN International, a global association of writers based in London. To date, he has written five novels in Turkish, which all have been translated into nearly 50 languages in more than 40 countries.

Sonmez studied law at university and started his career as a lawyer before becoming Editor-in-Chief of Ayrinti Publishing, one of the leading Turkish publishing houses. He has received numerous national and international awards, including the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Literature Prize and the Vaclav Havel Library Foundation’s “Disturbing the Peace” Award. Sonmez, whose articles have been published in reputable newspapers such as La Repubblica, Der Spiegel, and The Guardian, currently lectures on human rights and English literature at Cambridge University and gives seminars in different parts of the world. His latest novel – the first he has written in Kurdish – Evindaren Franz K. (Franz K.’s Lovers) was published in Diyarbakir by Lis Editions.

Kurdistan Chronicle sat down with Sonmez to discuss his perspectives on Kurdish literacy, impressions on Kurdish literature, his work at PEN, and his “return” to his native language in writing Franz K.’s Lovers, a development greeted with great excitement among the Kurdish literature circles as an encouraging example for Kurds writing in other languages.

Kurdistan Chronicle (KC): The novels you wrote in Turkish have been translated into nearly 50 languages in 40 different countries. After five novels, you returned to your native language, Kurdish, with a powerful story. Can you tell us about your Kurdish reading and writing adventure and what motivated you to author a novel in Kurdish?

Burhan Sonmez (BS): I learned Kurdish in our village, within my family, so it was nothing more than a spoken language, as we did not have the opportunity to learn the written language. Kurdish was forbidden, and the compulsory language in education was Turkish. Once I reached middle age, I started reading Kurdish texts and improving my grammar. It’s never too late for some things in life!

With this feeling, I intended to write a novel in Kurdish. I’ve had this desire for years but wasn’t sure which book to start with. While I was working on this novel, I felt that the time had come, and I started writing in Kurdish. One misses their mother tongue. We, the Kurds, are basically in exile in our homeland. Not only our land, but also our language has been taken away from us. In Turkey, where nearly 20 million Kurds live, the number of people who can read and write in Kurdish can only be counted in the thousands. This shame is not ours, but the state’s. If the state isn’t giving up this policy of oppression and denial, we must do our own work and protect our language.

KC: The journey of writers who return to their native language has always intrigued me. For example, although Kateb Yacine and Aime Cesaire knew French very well, they eventually returned to their native languages, with Yacine writing in Algerian Arabic and Cesaire in Martinique Creole. Samuel Beckett himself translated other books that he wrote in French or English into other languages. There are many other examples. As a bilingual writer, could you share your views on this subject?

BS: The feeling this situation creates in people is strange. Ours is different from, for example, the situation of an immigrant who knows Turkish but writes in German, or an academic who knows Italian and writes in English. Those languages are liberated languages; the transition from one to another is always free. In our case, our language was banned. It was forbidden to return to that language, and the only option was to leave it and join other languages, mainly Turkish, Arabic, or Persian. That’s why the ‘other’ language in a Kurd’s mind has always been his own language. In every Turkish novel I wrote, Kurdish words and images always seeped into the text. Unlike the transition between two liberated languages, we can talk about a transition between two different languages that can be characterized as a master and a slave. The reality of this and the psychology it brings to us is unique.

KC: Central Anatolia has its own dialect of Kurdish, which I find melodious. When I speak with you and listen to your past interviews, I can hear that melodious Central Anatolian Kurdish. Despite this, you chose to write in standard Kurdish. Why? Are we going to hear any of this dialect in your future novels?

BS: I thought about this, too, and am aware that the Kurdish I use is the standard dialect. The main reason for this was that while learning and improving Kurdish grammar, I felt like a student and stuck to what I learned. The Kurdish dialect of my hometown is different, and I dream of writing a novel in my own dialect one day. I don’t know how long it will take, but dreams are meant to be realized.

KC: In a previous interview, you said, ‘I read my first Kurdish book when I was 35.’ What have you read since then? What contributed to your Kurdish being so deep and rich?

BS: When I first went into exile, I embraced English because the basic condition for living in the UK was to learn this language. Recently, I have read books in Kurdish rather than Turkish and English. The internet was also of great help, as I followed online publications and articles. These days, I have a special interest in reading novels written in Kurdish by young writers.

KC: You are an avid reader of Kurdish literature. What impression do you have when you read it?

BS: I am excited by the language used by the young generation because I see that they are not simply content with trying to establish a unique literary language, but are also trying to develop the Kurdish language that they already use in their own creative way. I have heard some people critique this path, saying: ‘You can’t even understand each other, Kurdish is different in every region, how will you create a national language?’ I think this signifies our uniqueness. A language that is compressed into a single form and whose other interpretations are cut out, in my opinion, sterilizes itself. However, if Kurdish can preserve and develop the richness of its local dialects, this would be an important step. Look at the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse, who won the Nobel Prize in literature last year. He was able to become a world-class literary figure with the books he wrote in the minority dialect of Norway.

KC: The last time we met, you purchased Kurdish translations of several world classics from the bookstore. What do you read besides the classics?

BS: I try to read as many novels as I can, old and new. Apart from that, I read in my own areas of interest. For example, I like to read about history, archaeology, astronomy, and philosophy.

KC: When I heard about your Kurdish novel Franz K.’s Lovers, the name caught my attention, and as someone who loves Kafka, the more I read it, the more it drew me in. I liked it very much. How did you determine the name and the content of your novels? Why Kafka and Europe in a Kurdish novel?

BS: In my previous novels, I wrote stories about the events in Turkey and, of course, the problems faced by the Kurds. When I was writing in Kurdish for the first time, I made a special effort not to talk about these problems. Kurds have a reputation all over the world for being a suffering people. The world doesn’t see us, only our wounds. It doesn’t see our soul because our wounded body is at the forefront. While I was writing in my own language, I did not want to reveal my wounds to anyone. Instead, I wanted to sail out into the world and write about a subject that seemed to belong to others. I wrote about the effects of the ‘68 youth movements in Europe and the literature of Franz Kafka. When my book is published in other languages, I want everyone to read about these topics from a novel that is originally written in Kurdish.

KC: How did Turkish writers and scholars react to you writing in Kurdish? Did anyone encourage you, or did you receive criticism?

BS: I can’t say I’m very encouraged. On the contrary, while I was writing the book, everyone asked me, ‘Why are you writing in Kurdish?’ There were even some negative reactions after the book was published, which was what I expected, but I don’t want to talk about that. After all, we know the society we live in and the state of our country, so nothing surprises us.

KC: As a Kurdish writer, you were elected as the new President of PEN International on the 100th anniversary of its establishment, and you are still the president. I remember when you were elected, you gave part of your speech in Kurdish. What kind of work have you done in this position? Could you share your observations and experiences?

BS: We do so much that it is impossible for me to summarize, but I can draw a general framework. We have around 130 PEN centers and around 40,000 members around the world. As the world’s largest international writers organization, our core work is on freedom of expression. In other words, we defend and support writers who are under pressure. During the military coup in Myanmar, the Taliban coming to power in Afghanistan, or the wars in Ukraine, Gaza, or Eritrea – in other words, in the problems that arise all over the world – writers, journalists, and intellectuals, like everyone else, become victims and suffer the wrath of their states. That’s where we come into play. Turkey and Kurdistan are among the places where we work most intensively. Unfortunately, our region has endless troubles.

Mevlüt Oğuz is a journalist, poet, and activist working in the fields of civil society, culture, and the arts. He is a member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the Kurdish PEN affiliated to International PEN, and the Istanbul branch of the Human Rights Association (İHD).