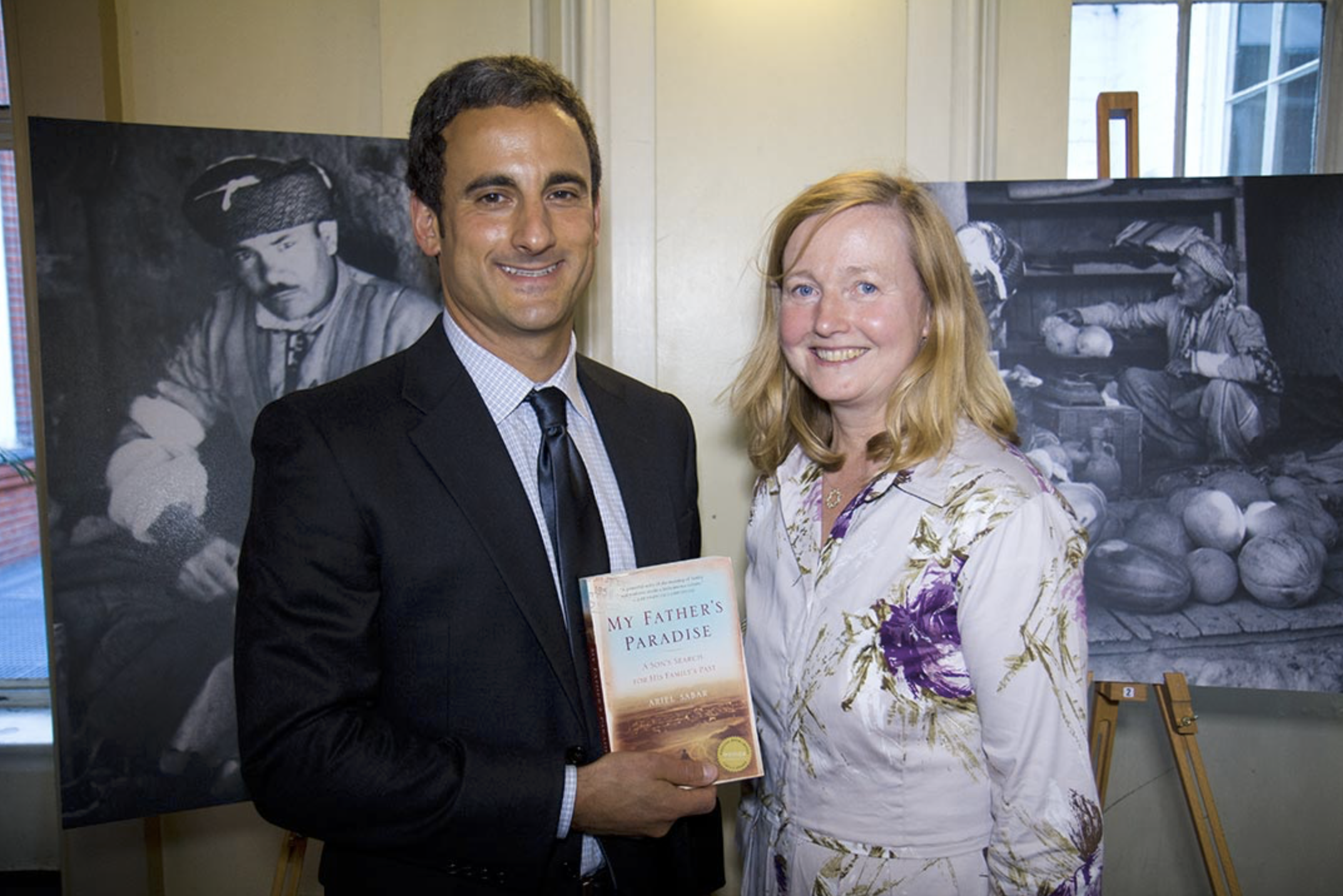

Diaspora and identity are especially pertinent concepts to the Jews of Kurdistan but they are also familiar to the two million Kurds living abroad. In retracing his father’s journey from the vibrant streets of Zakho to the academic halls of the United States, Ariel Sabar’s 2008 book My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Family’s Past not only highlights the historical plight of Kurdistani Jews, but also elucidates the parallel efforts of contemporary Kurds to maintain their culture and language while living in the diaspora. The book won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2008 in the category of Autobiography.

Sabar, through meticulous research and heartfelt storytelling, transports the reader to 1940s Zakho through the perspective of his father, Yona Beh Sabagha. The author diligently sets the scene for the narrative by providing a history of the biblical relevance of Jewish heritage in the Kurdistan Region, where the rugged mountains have sheltered Kurdish Jews for over 2,700 years.

Sabar also addresses the historical scarcity of Kurdish Jewish literature through his expressive writing and tone, which illustrate the rich tapestry of life in Zakho. Perched on the Khabur River, Zakho was home to Jews, Muslims, and Christians, who long lived harmoniously in a complex web of mutual dependence and cultural exchange. Sabar unpacks this tapestry by taking us on a journey that spans a century and multiple continents, delicately weaving regional history with the personal stories of his father and family.

The themes of diaspora, homeland, and integration are pivotal to both the narrative of this book and lives of many Kurds today. The towering mountains of Kurdistan have kept minority groups including the Kurdistani Jews safe for hundreds of years, and Sabar highlights how this sense of security was compromised as nationalist and sectarian conflicts erupted in the region in the mid-20th century. The author’s father undergoes multiple stages of personal transformation linked to the forced diaspora of his community, from emigrating from Iraq to seeking safety in Israel, as legal and social discrimination increasingly target Jewish communities in Iraq. Afterwards, Yona quickly realizes that to preserve the unique identity of Kurdish Jews, he needs to pursue his academic career in the United States, where he eventually settles.

Language as a lifeline

Identity, particularly through the lens of language, is another key theme of this book. Alongside providing safety from early warring empires, the mountains of Kurdistan provided another crucial component to the uniqueness of Kurdistani Jews: seclusion. While Jews in the rest of Iraq ultimately adopted the Arabic of their neighbors, Kurdistani Jews spoke Aramaic among themselves, which had been the common language of the Middle East for over 2,000 years. Language thus emerges as a vital identity marker in these remote Jewish villages, where inhabitants clung to Aramaic as they clung to their lives.

“Language was their lifeline to a time and place that no longer was,” Sabar notes in discussing the Kurds of Zakho.

For instance, his father Yona, as one of the last remaining native speakers of neo-Aramaic, leaves his family and close friends in the Kurdish neighborhood of Jerusalem for the United States, where he ultimately becomes a guardian of a language on the verge of extinction. Yona enters the world of academia in order to document and preserve this vital link to his childhood memories of a rich and diverse Kurdistan.

The themes of diaspora and identity are core elements of Sabar’s exploration of the plight of Kurdistani Jews, and these questions inherently resonate with contemporary Kurds who struggle to preserve their identity, culture, and language – even within their homelands.

As a Kurdish refugee living in the United States, My Father’s Paradise echoes my own personal experience of living in diaspora, as I also felt a renewed sense of inspiration of the diverse potential of Kurdistan. In recent years, Kurdistan has come to serve as a beacon of hope for over a million displaced peoples from neighboring countries fleeing conflict and religious or cultural persecution. Another role that Kurdistan can fill is to strive to embody the indigenous diversity represented in Sabar’s depictions of Zakho, a land where those of different faiths, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds can coexist and foster a sense of unity, where differences empower rather than embitter.

Sabar’s portrayal of the Zakho of yesteryear is an example of the possibility of peaceful coexistence, and so desperately needed in these times of distrust and violence.

Haima Askari is a D.C.-based consultant, facilitates collaboration among diverse religious and cultural groups. With a rich multicultural background, he’s worked in the German Parliament and conducted research with Amazigh tribes in Morocco.