Born in 1952 in Tirbespi in Rojava Kurdistan (Kurdistan in Syria), Bahram Hajo moved with his family to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq at an early age, where he witnessed the Kurdish Revolution of the 1960s and then the 1970 March Accord (also known as Iraq1-Kurdish Autonomy Agreement) between the Iraqi regime and the leadership of the revolution. He studied in Baghdad and Sulaymaniyah before moving to Europe, eventually settling in Germany.

We met Hajo in his studio in Münster at the end of 2023 and had a long interview with him about his fruitful artistic experience as well as his life story, fraught with instability and characterized by frequent relocations. During the interview, he made it clear to us that painting was his greatest passion. He first studied archeology and then devoted himself to painting in 1989, making a lasting impact on the world of contemporary art. His paintings are sold for large sums of money and still decorate many art galleries in cities worldwide.

We started by asking him about the large Hajo family, who are scattered throughout the world, just like other Kurdish families who were forced by the de facto political situation in their countries to immigrate in search of a safer life. The Hajo family has produced musicians, politicians, and artists who have played a major role in revitalizing contemporary Kurdish art and culture.

A family scattered around the world

Bahram Hajo (BH): I can’t provide a fitting answer to explain our family. Perhaps being so mixed through marriage with other Kurdish families helped it to grow and become more influential. As you know, the issue is sometimes related to genes. For example, my father Youssef Ibn Hajo used to play the saz (baglama), and I learned how to play thanks to him. He used to play at family gatherings, as we drank and sang together.

Kurdistan Chronicle (KC): There is something else that caught my attention about your family. Your ancestors originally came from Turkish Kurdistan and moved to the Kurdish region in northern Syria. Later they scattered around the world, with a large portion joining the Barzani revolution. You studied in Baghdad, and part of your family moved to Iran after the collapse of the Kurdish revolution in 1975. Then you migrated to Europe. You might have been among the first Kurds to immigrate to Europe. Why didn’t your family stay in one place?

BH: Yes. This was the result of the injustices our family was subjected to. The Ba’athist government, on the recommendation of a Syrian intelligence officer named Muhammad Talab Hilal, attacked the families that supported the Barzani revolution in the 1960s. Our family was among them. I was eight when the revolution broke out and witnessed my family send gold, money, clothes, and even shoes to the revolutionaries.

The Hajo family even bought radio equipment from East Germany and sent it to the mountains, thus establishing the first radio station for the revolution.

I remember a Syrian army division going to support the Iraqi army, which was fighting the peshmerga. Trucks full of soldiers passed by our house in Tirbespi. They started cursing us, saying that they were going to eliminate the Barzanis and threatening to come back and kill us as well. They confiscated our family’s property so that we had nothing. Most of the Hajos were farmers. There were only a few educated people in our family, including Dr. Hazni Hajo, who was in Europe. Majeed was an officer, and Othman was a soldier in the French army in Syria during the Mandate.

KC: Yet you remained attached to the homeland. You said in an interview that you would like to have a grave in your hometown.

BH: Yes. exactly.

KC: But is there a difference between a person being buried in a foreign country or in his homeland?

BH: For me there is. It is better to have a grave on my land. I returned to Qamishli in 2010 and built a house there, hoping to settle for a long time and spend my holidays there instead of in France, Spain, or elsewhere. It is easy for me to go from Qamishli to the Mediterranean coast, for example, but the situation has deteriorated, and it is no longer possible to go back.

Teaching and engineering

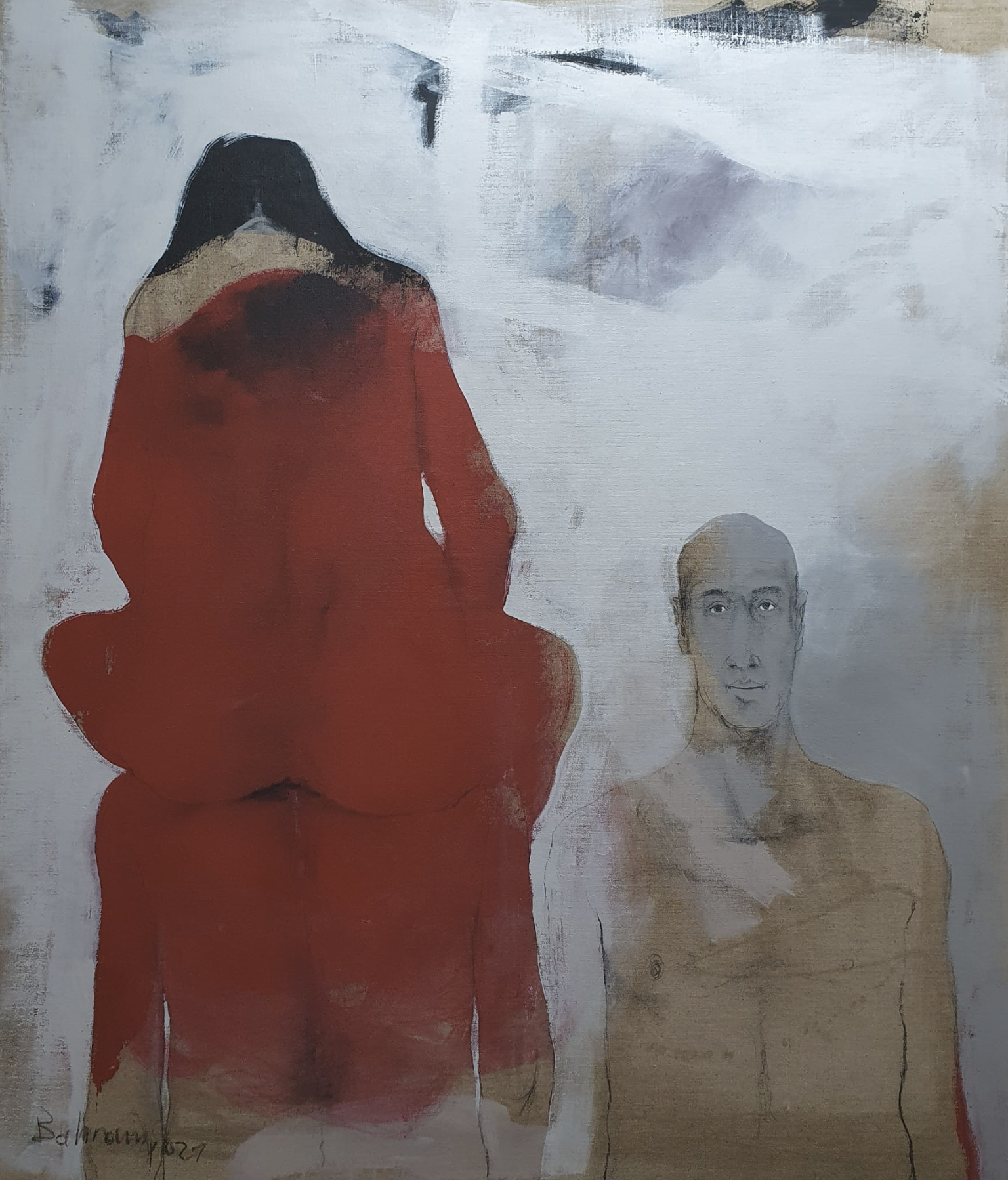

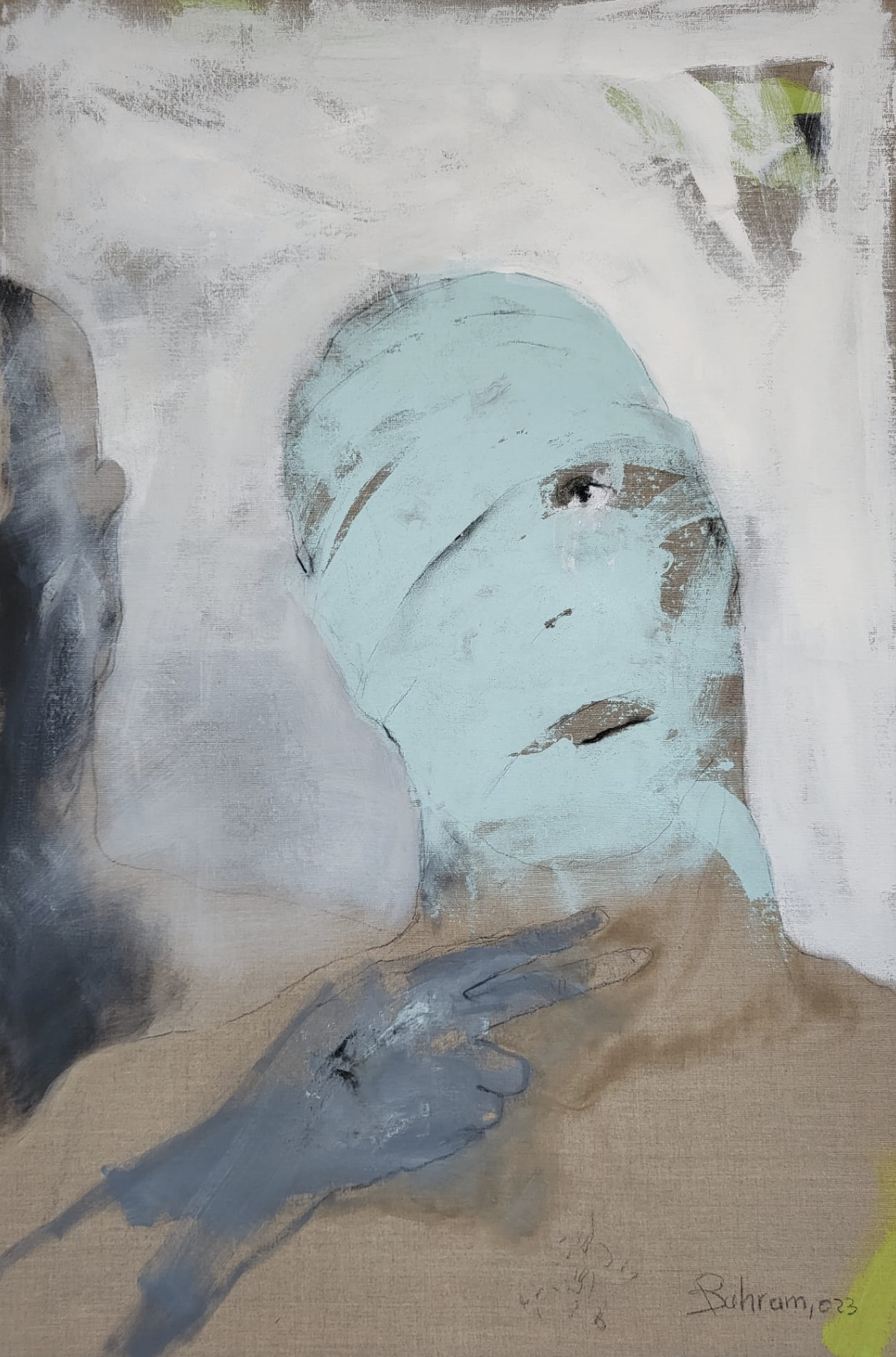

Hajo’s answer was followed by a five-minute walk to his studio, which was full of paintings, some finished and a few still in progress. I started studying the portraits, which included crushed, naked figures twisting in torment. Some resembled nightmares, full of pain and alienation. After a short tour, we sat on a leather sofa in the middle of his studio.

KC: Your paintings sell for high prices. You have a worldwide reputation. Some famous people buy your paintings, yet you say that you do not paint to sell them. If you had not been able to sell your paintings, would you have continued painting?

BH: Yes. I left my main job to commit myself to painting. I was a schoolteacher and translator, and my job brought in a decent salary to live on. Back then, my German wife – whom I met at the University of Münster in 1976 – did not support me the way that my wife Fatima does now. Still, I was adamantly dedicated to painting.

KC: Did you come to Germany when you were young?

BH: Yes. In 1974.

KC: Did you study in Baghdad?

BH: Yes. I went to Baghdad. At the age of 18 I was studying in Sulaymaniyah. I was at university studying for my baccalaureate degree when the Iraqi–Kurdish Autonomy Agreement of 1970, also known as the March Accord, was signed. At that time, there was an urgent need for teachers in Kurdistan. After the agreement, Arab teachers had to return to their cities after spending some time teaching in Nawprdan, Haji Omaran, and elsewhere, leaving the schools almost without teachers. My father explained the situation to my cousins Prshing, Brusk, and I, asking if we wanted to become teachers. Despite the lack of strong motivation, we opted to become teachers in Nawprdan. Dr. Hazni Hajo had come from Germany to work as a doctor. He and Dr. Mahmoud Othman were the only doctors of the revolution. The leader of the revolution, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, used to come from time to time to Nawprdan, and I met him many times. The political office of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) was in Nawprdan, and Dr. Hazni’s hospital was their headquarters.

KC: Do you have any special memories with the late Barzani?

BH: I can say that I saw him every week. During the year and a half that I spent in the region, in Galala and Nawprdan, I attended the KDP councils with my father and uncles. The late Barzani often rolled cigarettes from his own box of tobacco and offered them to the attendees. He would also offer one to me, even though I didn’t smoke then.

One time, an Italian journalist asked me about Barzani after he saw his picture: ‘Is this your grandfather?’ I told him, ‘He is my grandfather, but not my biological grandfather. He is like the Kurdish Garibaldi.’ When the newspaper published the interview, accompanied by pictures of my paintings, it said: ‘Barzani is like Garibaldi to us.’

I remained in the region until mid-1971, when the University of Sulaymaniyah established the Department of Kurdish Literature and the Department of Civil Engineering. Kurdistan enjoyed relatively peace after the March Accord. Kurdish ministers were appointed to the government, and Kurdish ambassadors were assigned to Iraqi embassies abroad. If my memory serves me well, Mohsen Dizayi became the governor of Sulaymaniyah. I had met him many times in Nawprdan. One time he took me in his car to Sulaymaniyah University and advised me to study at the university there, saying, ‘You did not come here to become a schoolteacher. You must pursue your studies.’

In Sulaymaniyah, I received a scholarship from the KDP amounting to 25 Iraqi dinars, in addition to 15 Iraqi dinars from the university. This was a large sum at that time. I started studying civil engineering in English. Brusk and I were staying in the teachers’ accommodations. Dr. Sherko Abid, who recently passed away, was one of those teachers. He was a chemist who studied in London until he returned to teach us physics and chemistry.

Studying civil engineering did not appeal to me. I was weak in subjects such as mathematics but wanted to study fine arts, theater, or music. I moved to Baghdad to complete my studies in engineering. I passed the first year successfully, but my grades were very low. So, I decided to leave my engineering study.

“You are in West Berlin”

BH: I stayed in Baghdad less than a year. Disagreements quicky broke out between the KDP and the Ba’athist government in Baghdad in 1972 and 1973. Kidnappings became frequent and many problems arose. At the time, I was staying with Prshing in a student housing complex. One night, I was with Ezzat Kettani, whose father was a martyred revolutionary officer. Ezzat was staying at the house of his uncle, who was a colonel in the Iraqi army. When I got back, I was told that the authorities had taken my cousin Prshing and that I had to go into hiding. They had taken him directly to the Qasr al-Nihaya, a palace the Ba’athist regime had turned into a prison.

At that time, Sami Mahmoud was a minister. He and Dara Tawfiq, the editor-in-chief of the party’s newspaper, Al-Ta’akhi, agreed to try to issue me a passport. Meanwhile, I hid in the house of the Kurdish poet, Hazhar Mukryani, in Old Baghdad. At the time, Mohsen Dizayi had become Iraq’s ambassador to Czechoslovakia.

KC: What happened to your cousin Prshing?

BH: The Ba’athist authorities released him several months later in an exchange deal. Three Syrian Kurds were exchanged for eleven Iraqi officers who were prisoners of the peshmerga. After that, Prshing moved to Germany and passed away when he was very young. He had been brutally tortured at Qasr al-Nihaya. They pulled out his nails and teeth and practiced the worst types of torture on him. He was a handsome boy with a graceful stature, and we used to call him Shammi Kapoor because he was so handsome.

After a sigh of sadness and regret, we resumed our interview.

I remained in hiding until my papers and passport were ready. Then I left Baghdad on a small plane with about thirty passengers. I think they were British diplomats who were friends of the Kurds. The plane landed in Prague and then took off to another destination. Friends had provided me with recommendation papers to study in Prague. I went to Mr. Mohsen Dizaye, the Iraqi ambassador in Czechoslovakia, but the Iraqi government had summoned him to Baghdad fifteen days after my arrival. I was left alone, not knowing where to go. Fortunately, during those two weeks, I had met a young Kurdish man from Afrin named Muhammad, who was staying in the student housing and doing a degree in medicine. He offered me his room, while he stayed with his Czech friend who was also studying medicine. I remained perplexed for about twenty days, not knowing what to do. It was not possible to study without a scholarship in socialist countries. I was told that I had to exchange five dollars daily, which was equivalent to fifteen Deutsche marks at that time.

Some advised me to go to West Germany via East Germany. I only had a passport, and my Iraqi visa was sufficient for three months of wandering around the socialist countries.

I resorted to traveling by train and had a guitar with me. On December 24, 1973, I arrived in a town called Teplice on the Czech-German border. There, four policemen boarded the train, two of them were Czech and two East German. I started playing my instrument, pretending that everything was fine. They asked me for my papers, so I gave them my yellow and white passport, which was in Arabic and English. They did not understand what was in the passport because they did not understand the languages. They took me off the train and escorted me to a police station, where I was detained for the night. I spoke English fluently because I studied at Sulaymaniyah University in English. I somehow made them understand the need to contact my friends in Prague. So, I was allowed to make a call to my friend Muhammad.

Things went smoothly after that. They stamped my passport, and I entered East Germany, where I was told that I had to take the metro to Friedrich Strasse station. I did not know that this station was in West Berlin until I asked people how to travel to West Berlin. ‘You are in West Berlin,’ they said. I finally arrived at my brother’s house.

Style and experience

KC: Let’s go back to art and your paintings. All or most look like self-portraits. You are the hero of your paintings. What is the motivation for this? What message do you want to deliver?

BH: I will answer you without philosophizing the topic. The face I see most is my own. I see myself every day in the mirror. I can draw myself so that others can easily recognize me. Plus, my baldness matches the canvas (laughing). If you draw a head with hair, it will not be beautiful.

KC: You said in one of your interviews that a person’s bare skin is enough to express the artist himself and that he doesn’t need any clothes!

BH: Yes. I originally work on my painting briefly with color but leave areas of the canvas uncolored. This is what drew attention to my way of drawing. I may be the only one who works this way.

KC: Yes. You leave a large area in your paintings with no color at all. And you give women a distinct presence in your paintings! We see this duality of man and woman in almost every painting of yours. According to my understanding, some of your paintings portray hallucinations and nightmares. We see faces bearing the hardships of life. There is also pain in your paintings, as well as mystery.

BH: In my life, I have encountered many social challenges. I closely observed the disputes that break out between men and women. Personally, I did not live a comfortable, luxurious life.

These things are reflected in my paintings and their characters. I carry the concerns of contemporary man and depict them visually into paintings that show my visage, which can portray men in general and, of course, me. I wanted to highlight the suffering of oppressed people in particular. People who suffer from despair, boredom, and brokenness. These things are not far from my personal experience.

My guest then talked about his relationship with the late Syrian-Kurdish artist Malva (Omar Hamdi), who died years ago in Vienna after leaving behind a massive body of paintings. He spoke of meeting Malva for the first time in 1991 in Vienna at Hajo’s solo art exhibit. He also told us about the exhibitions he held here and there, and his travel to Syria encouraged by Malva. I then returned to discussing the paintings that surrounded us, in which I could see characters that looked at us with patent pain.

KC: I would like to return to the topic of the voids or spaces you leave on the canvas. We find large areas in your paintings that you leave blank, unpainted. We know that artists usually do not leave a point or a small spot on the painting without working on it color-wise. What do these colorless spaces in your paintings tell us?

BH: The uncolored spaces in my paintings symbolize human loneliness. Even when I draw two people in one painting, voids surround them. They are alone. They are alienated and no one cares about them. This is repeated in my paintings and is a symbol of human alienation.

KC: Is your Kurdish national affiliation reflected in your paintings? How?

BH: That’s a difficult question. I cannot claim that I draw Kurdish faces. My characters may have oriental features, but they would not necessarily be Kurdish characters. I think that my identity as a Kurdish artist and the creator of these paintings is a reason for me to be proud. Wherever I am, in all my interviews, I talk about my belonging. I am a Syrian Kurd, and I paint for the world.

I feel pain when I find people criticizing the great Kurdish writer Salim Barakat because he writes in Arabic. I know him well and have sat with him several times. We are from the same generation. It is enough for us that he is Kurdish and that he conveys our story as Kurds to others.

Jan Dost is a prolific Kurdish poet, writer and translator. He has published several novels and translated a number of Kurdish literary masterpieces.