Life is full of surprises and unique journeys. For Dyar Ali Kamal, a 46-year-old associate professor of linguistics from the Kurdistan Region, life has proved to be a truly one-of-a-kind journey.

In 2021, Dyar traveled to China to teach the Kurdish language at Peking University in Beijing. Originally founded in 1898 under the name Imperial University of Peking, it is today one of China’s most prestigious institutions of higher learning.

This opportunity originally emerged out of a cultural exchange program initiated in 2019, when Salahaddin University-Erbil established the Department of Chinese Language – a rarity in the Middle East, where only Iran, Turkey, and the Kurdistan Region offer such programs.

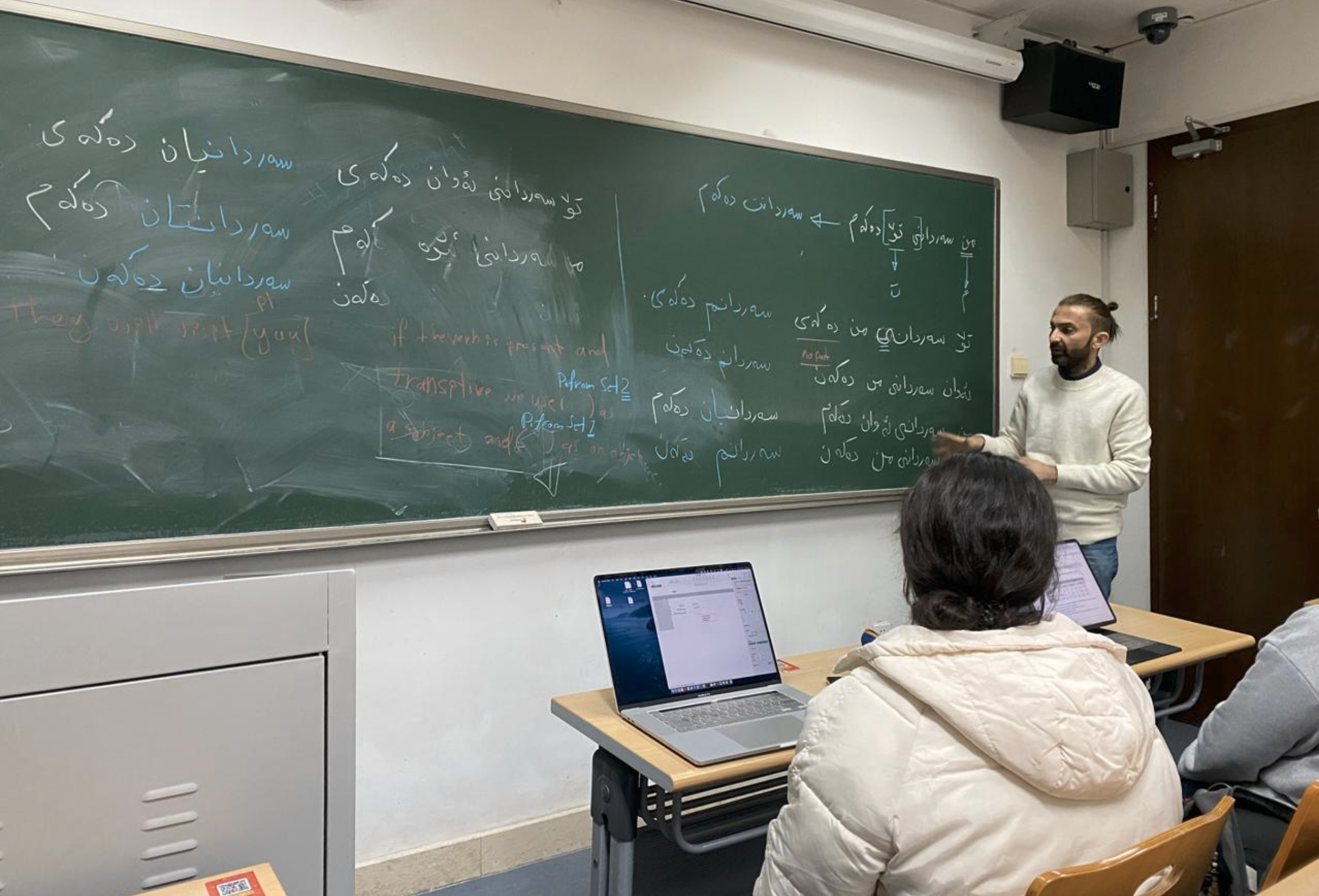

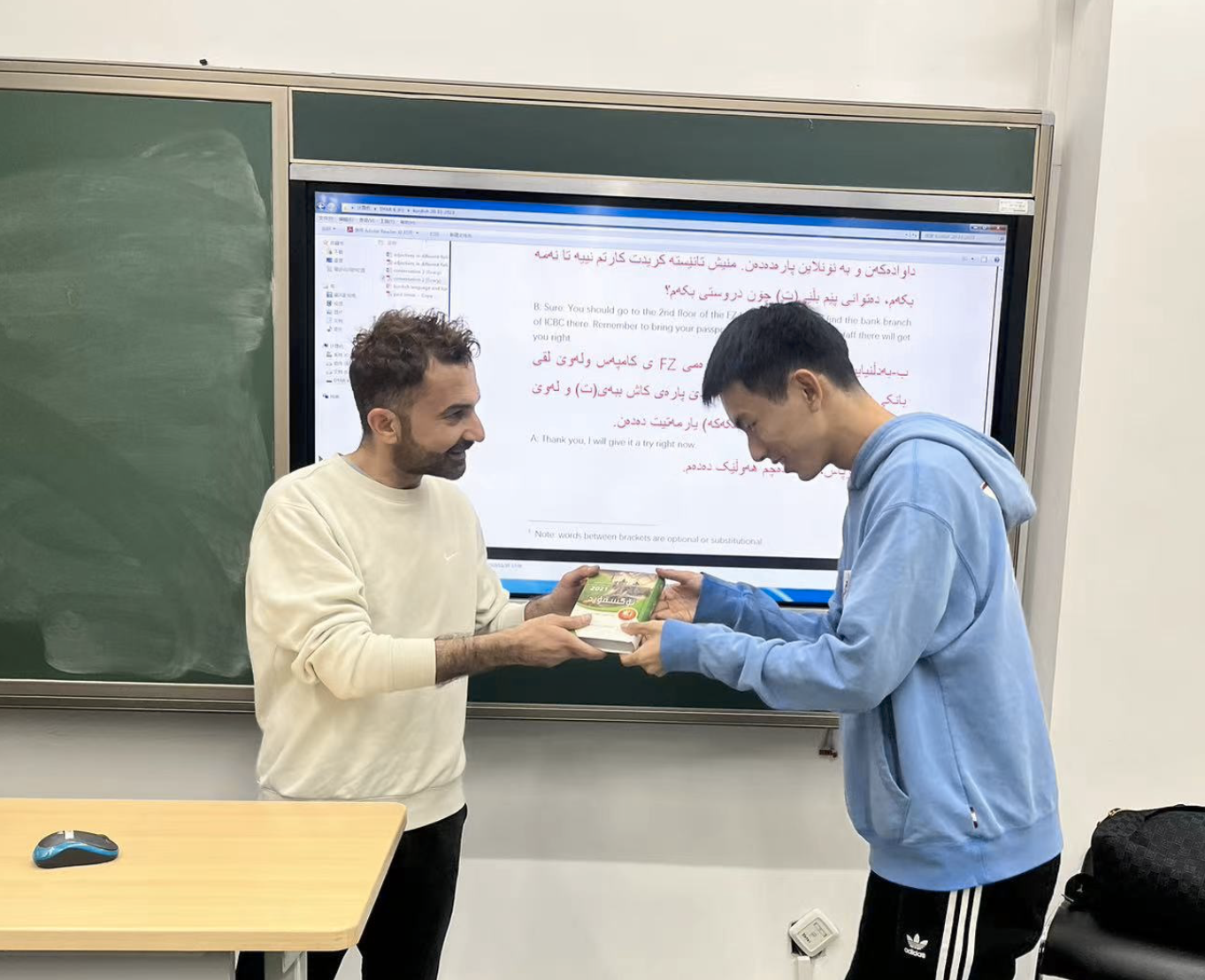

Dyar was initially slated to move to Beijing in March 2020, but the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic forced him to conduct his first year of courses online. However, in 2021, he finally met his students in person at Peking University and taught Kurdish for four hours per week.

Dyar described his journey as a challenging yet rewarding experience when he spoke recently with Kurdistan Chronicle. “There are no unified Kurdish language programs for foreigners,” he says. “I have had to adapt, drawing on my knowledge of the Chinese language and culture to create a practical curriculum for my students.”

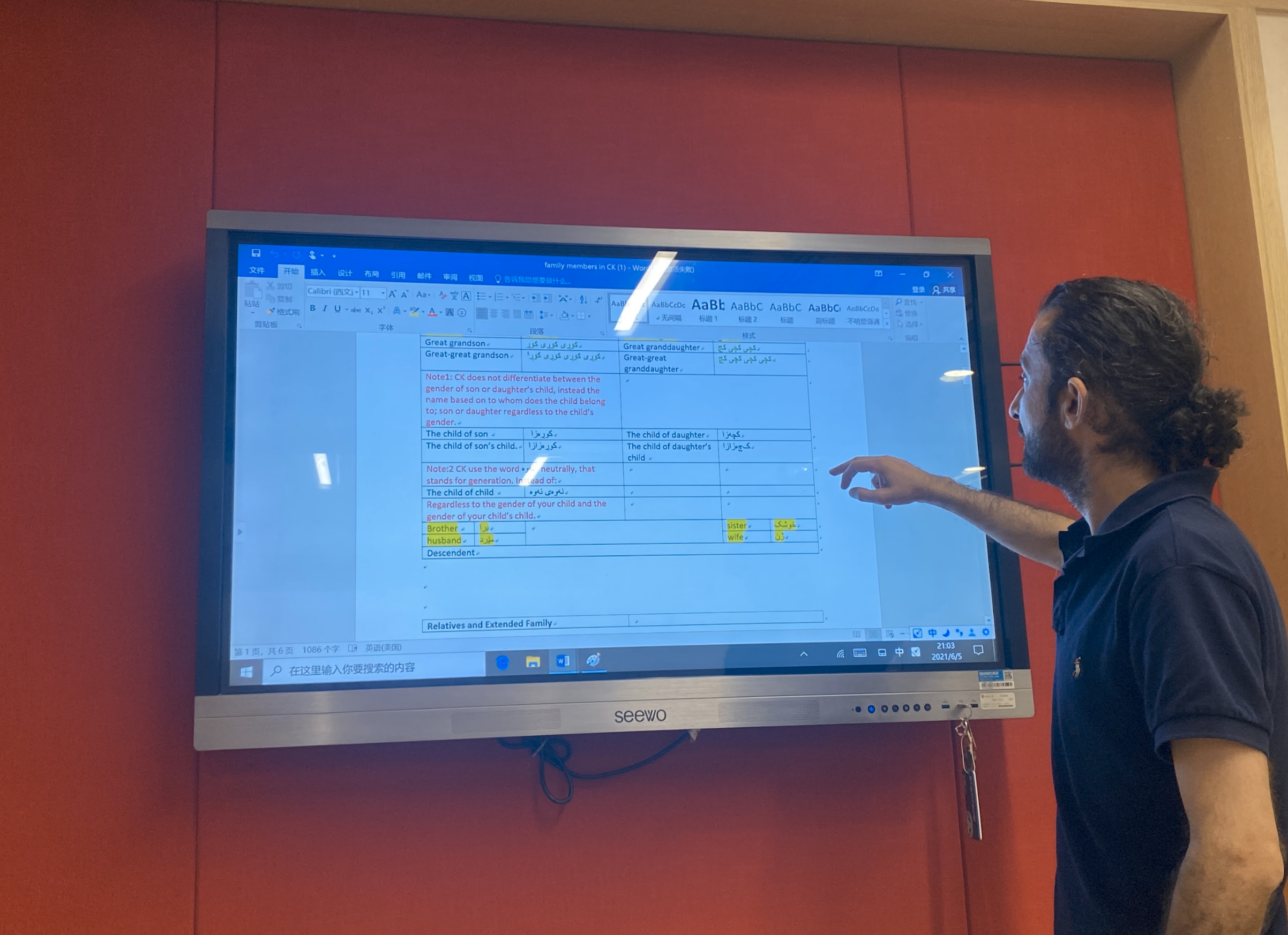

Dyar has concentrated on teaching the Sorani dialect, which is the official language of the Kurdistan Region under the Iraqi Constitution. He has also incorporated elements of Kurdish culture into his lessons. “The students are fascinated by Kurdish culture,” explains Dyar. “They ask about our traditions of hospitality, celebrations such as Newroz (Kurdish New Year), wedding and funeral customs, and even epic mythologies.”

Dyar has noted parallels between Chinese and Kurdish cultures. “Both cultures hold family in the highest regard,” he observes. “Traditions, values, and social structures revolve around the family unit, and elders are revered for their wisdom and guidance.”

When asked for advice for aspiring Kurdish language learners, he emphasized the importance of historical context. “Seek out credible sources on Kurdish history,” he urges, “and do research into established grammar resources like those by David Neil MacKenzie.”

Despite leaving China after his contract ended, Dyar has remained optimistic about the future of the Kurdish language in China. “I believe a dedicated Kurdish language department within a Chinese university is right around the corner,” he says. He encouraged other Kurdish language instructors to pursue similar opportunities, emphasizing the enriching experiences they provide.

He added that his students in China were passionate about traveling to the Kurdistan Region, saying that “Kurdish people have sublime virtues and good manners; plus, Kurdistan has deep history and beautiful landscapes, some reminiscent of landscapes in China.”

Dyar’s sole difficulty was a mandatory three-week quarantine that he undertook upon arrival in China. Nevertheless, he looks forward to returning someday, not as a teacher, but as a tourist eager to explore the vastness of this fascinating country.

Distinction between Kurdish and Farsi

One question frequently posed to Kurdish language teachers or Kurdish people is the degree of similarity between Kurdish and Farsi. Both languages, indeed, belong to the vast Indo-European family tree, sharing a common ancestor.

Dyar, who has been teaching Kurdish since 2003 and has conducted numerous Kurdish language studies – including a comparison of Kurdish and Farsi languages – said that both Kurdish and Farsi are Aryan languages. Aryan does not refer to an ethnic group of people or a specific DNA, as is often misunderstood, but rather to a linguistic group of people who speak Aryan languages, such as Kurds, Persians, and Pashtuns in Afghanistan and India.

“In terms of chronology, both Kurdish and Farsi exhibit notable similarities. However, when it comes to sentence structure, grammar, tense, and pronunciation, Kurdish differs significantly from Farsi,” Dyar proclaims.

Dyar agreed with the notion that Kurds have preserved their language more purely than Persians, arguing that ethnic groups facing existential threats are less open to external influences and thereby safeguard their language. In contrast, he maintained, Persians have historically been more open to other cultures and languages because they have not faced existential threats like the Kurds.

Qassim Khidhir has 15 years of experience in journalism and media development in Iraq. He has contributed to both local and international media outlets.