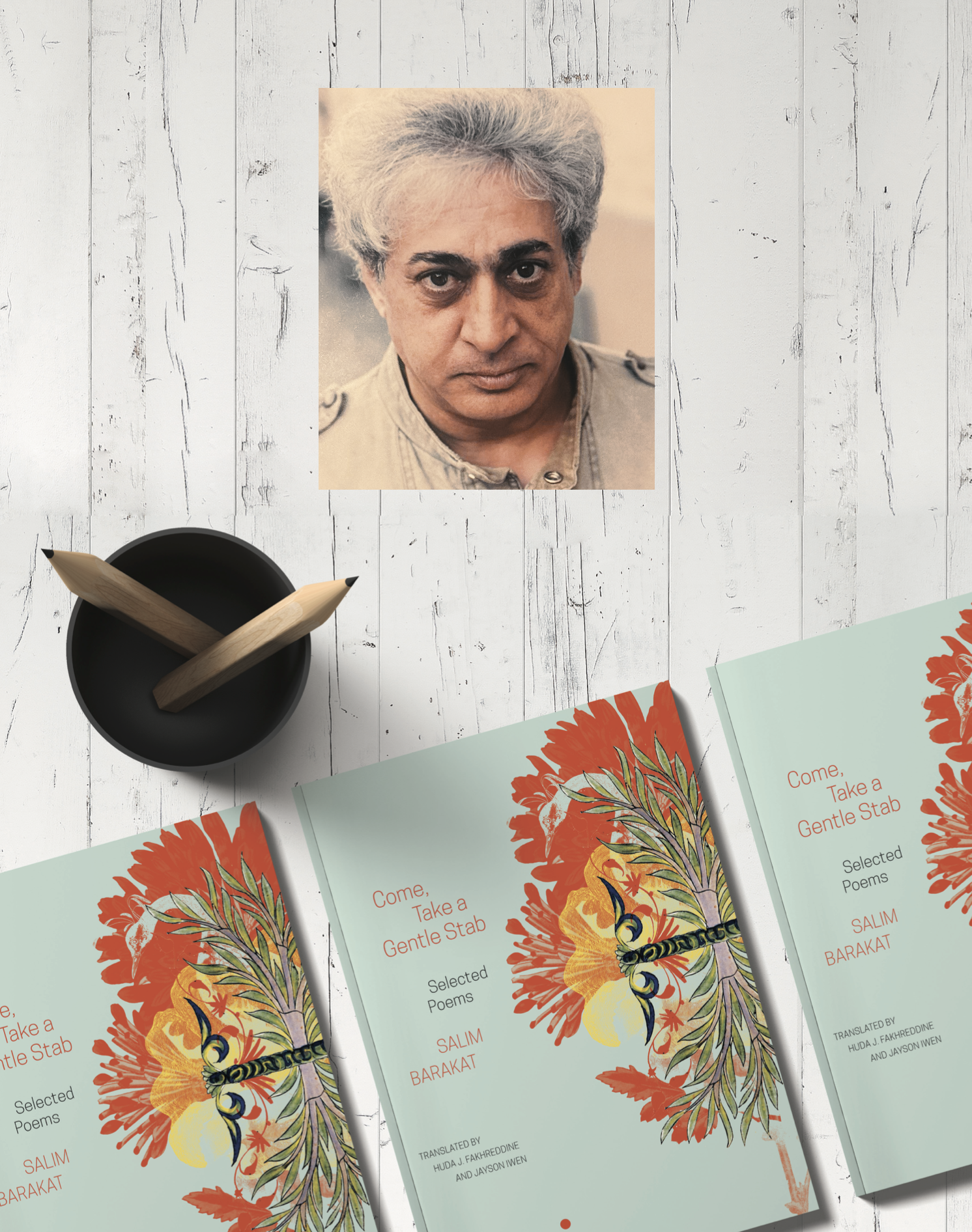

Salim Barakat is a Syrian-Kurdish writer who writes in Arabic and is well known for leaving a unique mark on contemporary Arabic literature, especially in both poetry and novels. He has published many anthologies of poems and novels since the early 1970s, and his works have been translated into many languages. Arab critics consider Barakat to be the best author to write in Arabic to date because of his captivating and powerful style and language. Now 72 years old, Barakat started writing poetry and published his first poetry anthology at an early age. He then quickly caught the attention of critics in Lebanon and Syria, who heralded the birth of a poet who would have a lasting impact on the future.

With his famous 1985 novel Jurists of Darkness, Barakat was ushered through the grandest gateway of writing novels, and his other novels soon appeared in successive publications until they amounted to nearly thirty in total. Many of his novels are set in the Kurdish community in Syria and offer rich panoramic scenes from the writer’s life, which is closely linked to the development of the Syrian-Kurdish community in the 1960s. Other novels relate to contemporary Kurdish history, including Al-Rish, which touches upon several of the Kurdish uprisings in the 20th century.

Salim Barakat lived a life of struggle, moving from one exile to another. From Beirut to Nicosia, and finally to Sweden, where he now lives in total solitude away from all sorts of communication, he devoted himself to writing and developing his creative career in stable circumstances.

Diversity disrupted

In this article, Kamaran Hoj, the Kurdish translator and critic, discusses one of Barakat’s most recent novels, The Roaring of Shadows in Zenobia’s Gardens, which casts light on the dark moments of suppression that puncture the co-existent community of different races, religions, and ethnicities that lives in Qamishli. Every now and again, Barakat ventures into writing about the northern region of Syria (Western Kurdistan). Diversity is at its heart, yet brutality has long tyrannized and dominated this region; so many regimes only want eternal totalitarianism, ignoring the cultural and social mosaic that resides there.

As in his biography, What About Rachel, the Jewish Lady?? begins with a question imbued with violence: “How long will this war last?” The question is posed by a child, Musa, the narrator of the story. It is asked not because he is interested in major issues, but rather because he has the right to live his usual life, contrary to orders that deprive him of the life he deserves. Musa, who is addicted to Western films, wants to watch Charlie Chaplin's Gold Rush, while the Six-Day War rescues his brother, Kayhat, from having to attend his hateful school.

The Osi family, consisting of a husband, two children, and a fetus, lives in a neighborhood where people of diverse races, religions, and ethnicities live in peace and harmony. It has become a place with a strong foundation because it includes Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, Armenians, Assyrians, and Jews, all in a city named Qamishli. The specter of war hovers over the city “with the deployment of intelligence personnel with their pistols visible under loose shirts” and the closure of “shops in the Jewish Quarter since the first outbreak of the news of the war”

Barakat sketches the lives of his characters, which intertwine just as the city streets intertwine with its residents. Osi, undocumented, with no records proving his identity with the state because of new regulations by new rulers, works at an electricity company and listens to the news of the war on his radio. The heart of his eldest son, Kayhat, is fixated on getting closer to Lina, Rachel the Jewish lady’s daughter; “from that day, when the first warm and resonant string of the harp of his young blood shook, Kayhat had tasked himself with the matter of purchasing from Rachel’s shop.”

Kayhat finds an opportunity to provide his services on a Saturday to the family, along with two of his friends, a Christian and an Arab, after hearing from them that Jews stop doing everything on their Sabbath, or holy day, and need someone to help them fulfill their chores. But when he knocks on the door of Ms. Rachel, an intelligence officer confronts him and interrogates him if he were a Jew. When Kayhat responds that he is Kurdish, we are immersed in an ironic cinematic scene, mixed with astonishment and condemnation, where Kayhat is “pale, disappointed by his poor intuition that got him into trouble.”

“There will be no American films in Syria, lad”

But the changes that disrupt this easy life do not stop for Kayhat, who asks Katia, his Christian neighbor, about the meaning of Farid Al-Atrash’s song, “We Have Been Brothers, Cross and Crescent,” after hearing it. She replies, “Our country is our mother. We are brothers and sisters.”

“What about Ms. Rachel? Why didn’t Farid Al-Atrash’s song find her a place between the Crescent and the Cross?” Kayhat asked her. “She is Jewish, and they are the killers of Christ,” she replies.

When Kayhat pays Rachel a visit to help her avoid committing taboos by working on the Sabbath, he notes the depth of the tragedy that has befallen her: “Kayhat felt a sting in his heart: there is something broken in the air. The war left a scattering of glass shatters above and below everything”.

After the victory of the voice, however “the army was defeated…Places, terrain, and parts of the sky were cut off from the map of the Arab lands”. Musa, who is Osi’s son, believes that he is the greatest victor and will go to cinemas again with his brother, but he is shocked by a victory of a different kind. In front of the Sheherazad Summer Cinema, they discover a new billboard advertising a movie named One Thousand and One Nights, starring the “screen monster,” Farid Shawqi. So, the Charlie Chaplin film will not be on, because “there will be no American films in Syria, lad”. Instead, “like stones thrown from the sky by birds in flocks, as compensation for Western films, there will be Indian films in cinemas”.

A love lost

After the war, the character wearing “the red fez” appears carrying a notebook “with the addresses of many houses in the neighborhood, along with their population numbers. He duly checks for the presence of its owners”. Kayhat is then surprised when Benjamin visits Rachel’s house with a Bedouin named Nabhan, who claims that he will help them on Saturdays. This leaves Kayhat in bewilderment, after “the name of a person from the Tay clan is mentioned in the disappearance of Jews, who has connections in the state intelligence”.

Kayhat, who is afraid of losing Lina, feels jealous of Nabhan and decides to declare his love to her. He asks his Jewish friends to write the word “I love you” in Hebrew so he can finally deliver the message to Lina, who is out of his reach:

“‘When will you reply to my messages, Lina?’ Kayhat asks.

‘What messages, Kayhat? When did you send it?’ she replies.

‘I haven’t sent it yet, Lina,’ he says”.

Meanwhile, Osi is fired from the electricity company because his son Musa writes on the blackboard at school “Long live Charlie Chaplin, leader of the One Nation Cinema”, and the art teacher is fired from work because a student reports him.

When Kayhat finally pulls himself together to reveal his feelings to Lina, he goes to her house and discovers “three men from state intelligence with their shirts drawn over their pistols wearing black glasses. The red fez man. Three men and a woman who are clearly Jewish in appearance, and the young Bedouin Nabhan. They were all in front of Rachel’s open gate”.

It seems that Nabhan worked to smuggle the family out of Syria. Kayhat is devastated. He puts the paper on which he wrote “I love you” in Hebrew in his mouth and turns it into chewing gum, perhaps out of fear of the intelligence services lurking around him. He buries it like a loving fetus, just as a mother buries her fetus in an unknown manner after a miscarriage, and throws it in the dirt, so the novel ends with: “Kayhat cried.”

Kameran Hudsch is a Syrian Kurd, who has resided in Germany since 1996. He has served as a lecturer at various German universities and has translated over 30 books from German and Kurdish into Arabic.