The Kurdish classical poets were more than mere versifiers who penned and recited poems during evening gatherings; their poetry also bore the marks of a deep engagement with the prevailing intellectual fields of their era, including astronomy, philosophy, mysticism, and religion. This depth also extended to the poets’ musical skill, which was more than an intellectual addendum and was manifested through their ability to play various musical instruments, their knowledge of musical modes (maqams) and vocalization, and more.

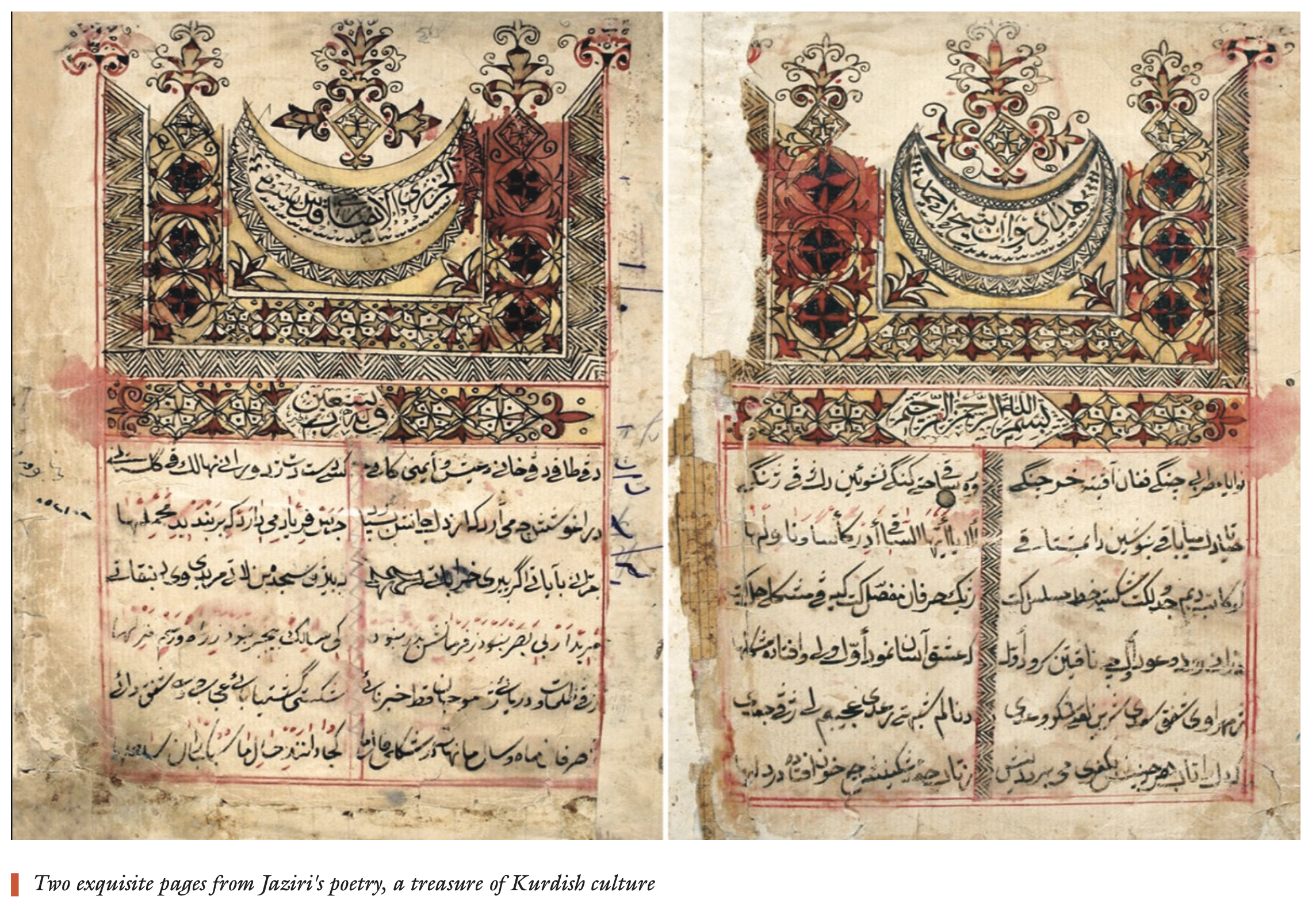

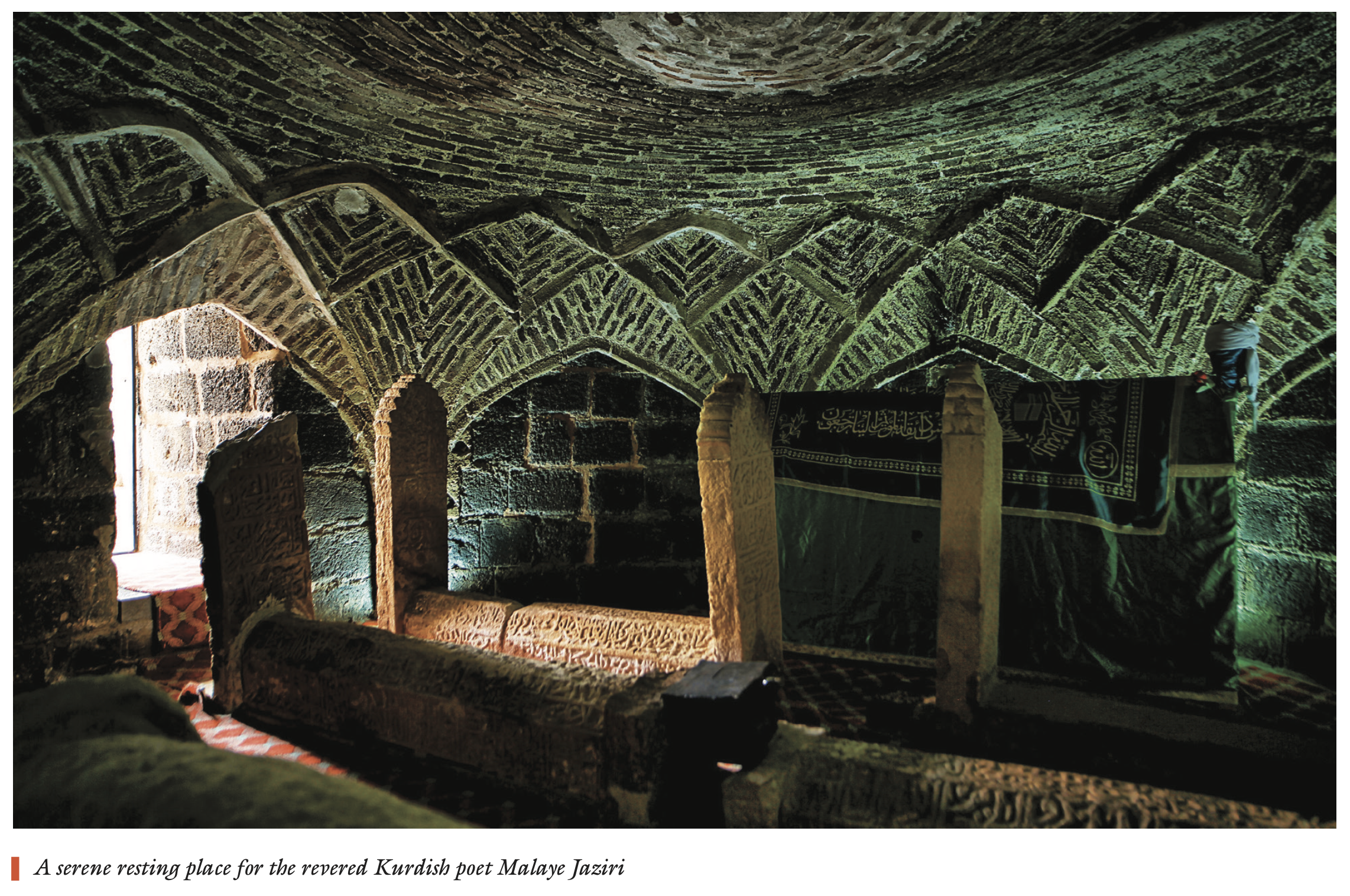

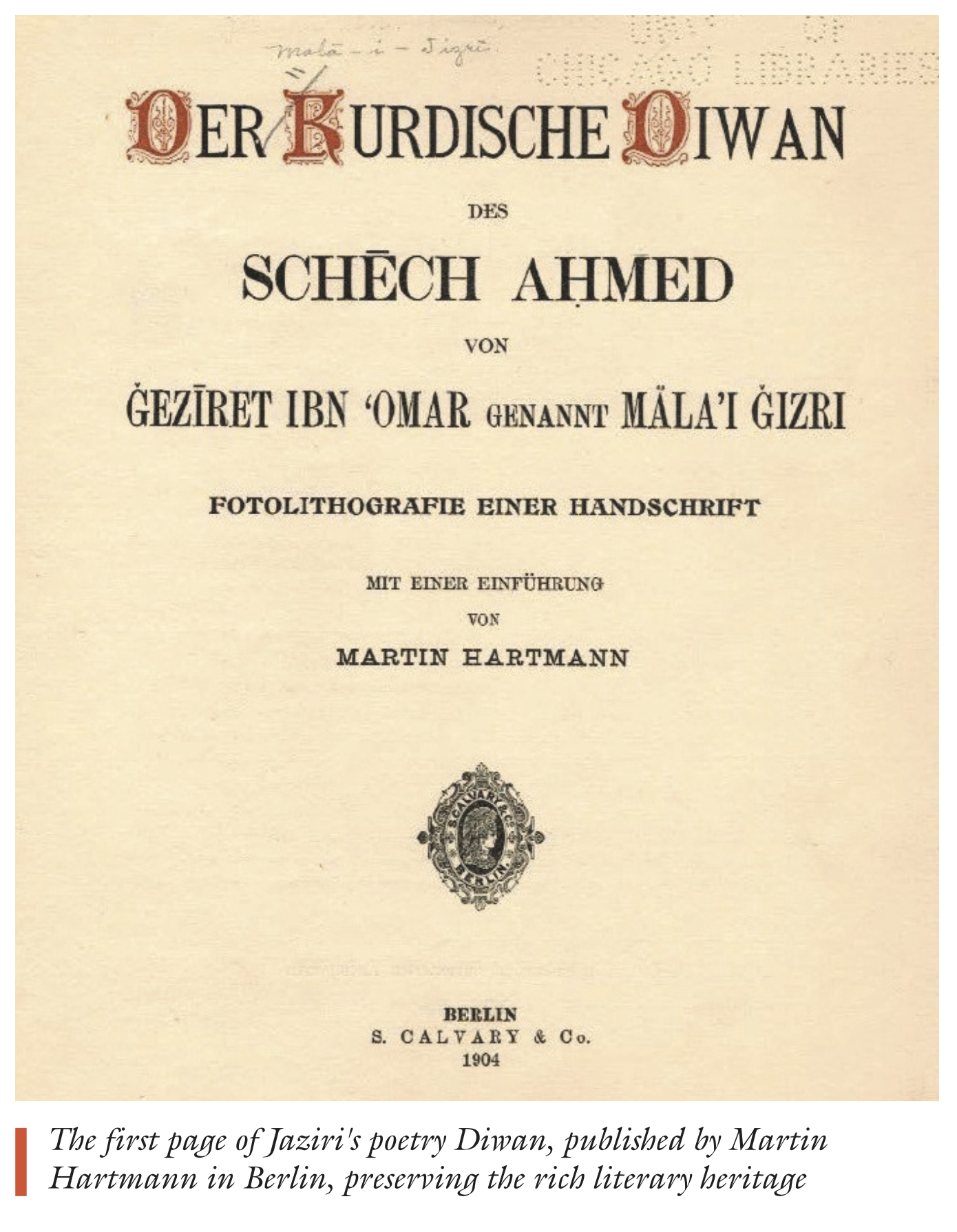

Malaye Jaziri (1570-1640) stands out among these polymath poets. The Kurdish poet and Sufi resided in Cizre in the Botan Emirate of the Ottoman Empire during the 17th century. His most notable literary contribution was his collection of poems titled “Dîwan/Divan,” a compilation that encompassed genres such as ghazal, qasîde, naʻt, and ruba’I arranged according to alphabetical order in Arabic. In his poems, Jaziri adopted three pen names: “Mela,” “Ahmed,” and “Nîşanî,” with the latter carrying connotations related to Sufism.

A synthesis of influences

Although earlier poets like Ali Hariri (1009-1080) contributed to Kurdish literature, Jaziri established the foundations of Kurdish classical poetry. His literary persona was shaped by three significant factors: his religious and mystical perspective; his exposure to the works of renowned classical poets like Hafez al-Shirazi, Saadi al-Shirazi, and Mevlana Jami; and the rich cultural backdrop of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Jaziri's literary identity is characterized by a synthesis of languages and influences. Despite the palpable influence of Persian poetry on his work, his language was not exclusively Persian, as demonstrated by his embrace of the Ottoman context. While he draws inspiration from Persian, Jaziri blends Kurdish, Arabic, and even Turkish elements into his writing, showcasing the diversity of his cultural palette.

Aside from the captivating lyrical and melodic qualities of Jaziri's poetry, his verses occasionally delve into musical themes, interweaving references to musical events, instruments, and melodies. For instance, in the opening verse of one poem, the voice of a singer merges with the sounds of a musical instrument called çeng (harp), gradually escalating until it reaches a symbolic reference point, the astrological sign of Cancer. This work of poetry encapsulates the interplay between musical elements and celestial imagery.

Jaziri's work also evokes other musical instruments such as the rûd and ûd, illustrating their use in expressions of love. The poet's verses resound with instrument names like ney, qanûn, rebab, and çing-i çîng (castanets), revealing an immersive musical atmosphere.

Melody and rhythm

Although Jaziri's poetry doesn't explicitly employ musical terminology like maqams in the manner of Ahmad Khani (1650-1707), there are glimpses of a sophisticated musical culture within his verses. In one verse, Jaziri beckons Mala to perform a ghazal beyond conventional boundaries, accompanied by the rhythm of tambourines and the resonance of the çeng. This suggests a nuanced familiarity with musical aesthetics and practices.

Furthermore, the concepts of reqs (dance) and sema (a spiritual dance) frequently recur in Jaziri's poems. He interprets sema as the mystical dance of Sufis, a means to experience divine rhythms within the heart. Notably, Sufism and its accompanying practices were the subjects of lively discourse in the Ottoman cultural milieu of the 17th century.

Jaziri's poetic legacy extends beyond mere poetic expression. His verses resonate with the echoes of intricate knowledge, music, and spirituality. By exploring Jaziri's work, we glean insight into the complex interplay between culture, language, and artistry during a pivotal era in Ottoman history.

Although Khani appears to possess a deeper understanding of terms, tones, and musical instruments compared to Jaziri, the music and rhythm present in Jaziri's poems suggest an organic musical spirit. This stands in contrast to Khani, who can be considered endowed with musical logic. The same can be said of their overall literary style; Khani embraces a clear nationalist project using literary and artistic tools, whereas Jaziri adopts an aesthetic project with less defined nationalist intentions.

Perhaps this is why many musicians are more inclined to compose and sing Jaziri's poems rather than Khani’s. Jaziri's poetry exudes a musical quality full of melody and rhythm that appeals to musicians.

Memo Seyda is a Syrian Kurdish songwriter, ethnomusicology PhD student, and a seasoned contributor to Kurdish music research, migration studies, documentaries, and translation.