During my childhood, I often heard the name of the city Adana and, when I was around eleven years old, I finally visited it. There, my eyes caught sight of the novel They Died Bowed Down in a bookstore. I immediately bought it, spending all the money that I had in my pocket. The book spoke about injustices, and its warm narrative deeply influenced me. Later, I would eagerly watch many films by the author of this novel, experiencing the same warmth.

Later, in the mid-1970s, I was a student at a Boarding Teacher High School in the Dağkapı neighborhood in Diyarbakır. It was a time when conservative forces held power in Turkey, and the ruling Nationalist Front (MC*) government, which included the MHP* party, aimed to place its supporters in teacher training schools where they would attack Kurdish and leftist students daily. I remember spending many nights at the coffee shops around the school. To momentarily forget this situation, we would often go to the cinema.

The film Arkadaş had just been released and so one weekend afternoon, I went to see it. I had seen some of Yılmaz Güney’s films before, but this one had a special impact on me. I discovered a courageous and truth-speaking protagonist with a slender figure from whom I had much to learn about resisting and standing up to the fascist pressures at school. With the strength I gained from the film, I started resisting these pressures, at least for a while. It didn't last long, and I was exiled to Balıkesir in western Turkey.

Later, I arrived in Germany before the military coup on September 12, 1980. After the junta, there wasn't a day when I didn't hear news of a friend being captured or killed in Turkey, as the military brutally attacking Kurdish freedom movement members and leftists with all its might. They were intervening in all aspects of life.

Escape

In exile, we monitored the situation in Turkey from afar. Those were very dark years. Blood was being shed on the streets and in the dungeons of my country. Our means of solidarity were limited. Many in exile didn't speak the language of the country they lived in and faced difficulties in resolving their personal problems.

Suddenly, news spread that Yılmaz Güney had escaped from prison and from Turkey altogether. How could this be? How had he managed to break through the prison gate with his slender figure? How had he managed to leave Turkey under strict military control?

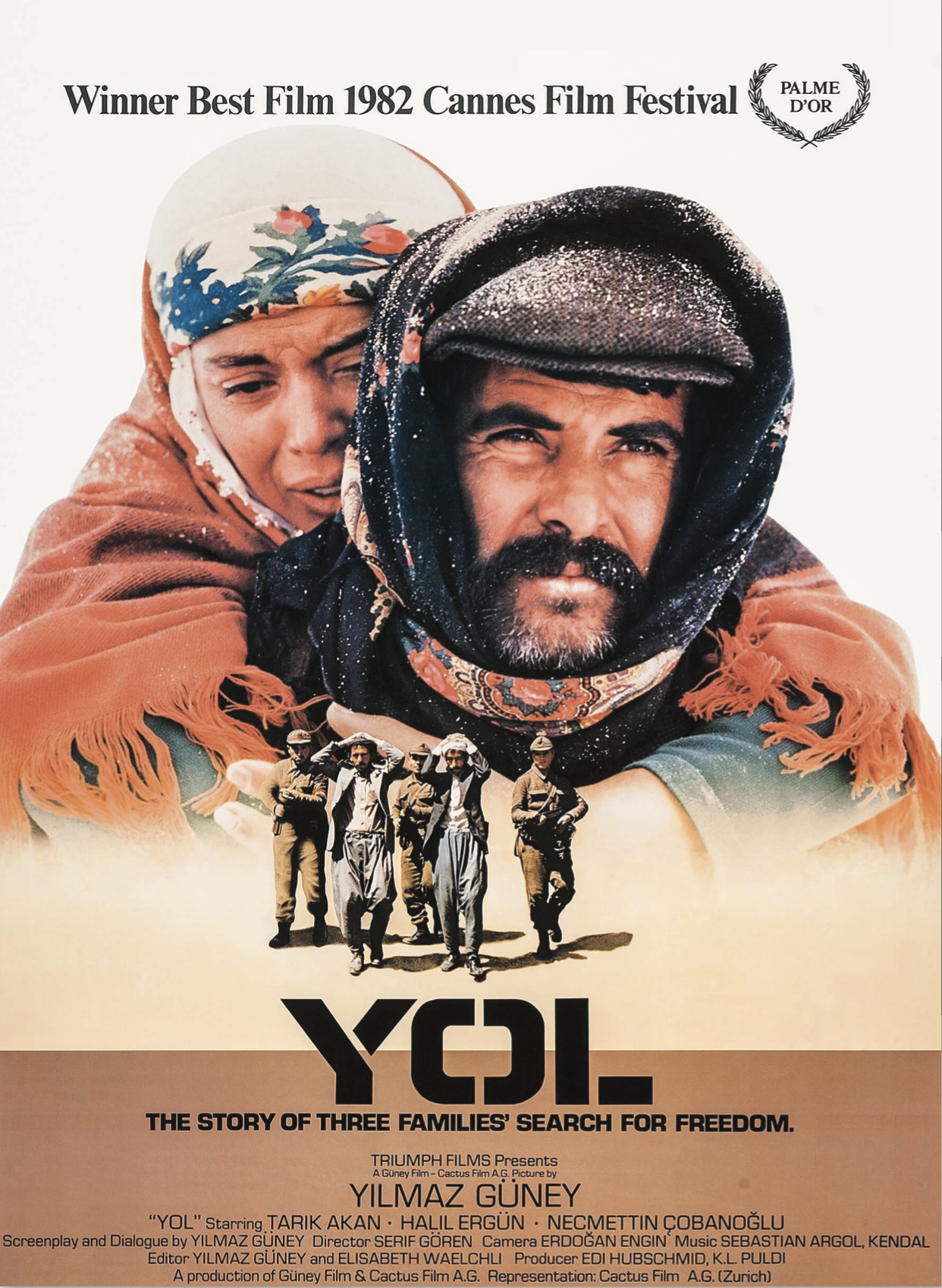

These questions nagged at me. Apparently, the power of the dictatorship wasn't enough to control everything. There wasn't a day when the Turkish media didn't publish a lie about Güney's escape. At the time, I was a subscriber to the alternative left-wing newspaper Taz (die Tageszeitung). My days always started with it, and one morning, I opened the paper to find a whole page dedicated to Güney and his success in Cannes. At that moment, Güney's letter to his wife Fatoş while incarcerated came to mind: "My body is in prison, not my mind. We will make films that will be talked about all over the world."

Undoubtedly, the success of the film Yol at Cannes, a significant part of which belongs to the author of this book, was not only the realization of Güney's words. It also, at that time, gave power to those who had been forced to flee, had been deprived of their citizenship, and were living in exile. So, being in exile was not a defeat. By receiving the Golden Palm, Güney had conveyed this message to those in exile.

Forever an inspiration

Yılmaz Güney is one of the few people who made me love books from an early age. In Arkadaş, he gives Ahmet Arif's poem, "I Wore Out Shackles from Longing," as a gift to the young girl Melike, who played the lead role. After watching the film, I went and bought that book of poems, even though I knew it could lead to my capture and exile or expulsion from school.

Wherever Yılmaz went, he carried books with him, recommending or gifting them. He was not just a reader and seeker of knowledge; he was also a distributor of knowledge. In her book, his daughter Elif mentions how he would frequently ask her questions about various subjects, such as "What is socialism?" or "What is Kurdistan?"

When asked to translate this book, I was hesitant. I already had a novel translation in hand, and the demands of my medical profession were quite intense. However, when I saw the photo narrative of this great personality being rescued from the clutches of a dictatorial regime, I changed my mind. A courageous Swiss man had clandestinely smuggled Güney out of Turkey under the harsh conditions of the Kenan Evren junta. Now, he had written his memories from that time. Thus, Güney became the person who empowered me to undertake the translation of The Ballad of Exiles.

Edi Hubschmid has written the story of Yol, from Isparta Prison to the Cannes Film Festival, with the care of a film producer. He has tried to keep the narrative limited to the events he witnessed as much as possible. Nevertheless, the warmth of the friendship between two men from different cultures, the experiences of Yoland of many other filmmakers, becomes apparent.

Yılmaz Güney wanted to accomplish much more. Unfortunately, passing most of his 47 years of life in captivity and exile didn't allow him to realize all his projects. He dreamed of a world free from oppression and exploitation. In his final years, he was occupied with the idea of making an epic film called "The Birth of a Nation." According to the information provided by Kendal Nezan, the president of the Paris Kurdish Institute, the film would be about Kurdish history and the Kurdish freedom movement in the style of D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation.

Unfortunately, his untimely death prevented this as well.

Husên Duzen a Kurdish writer, translator, and journalist from Mardin. He is based in Germany since 1979. He is an accomplished author with a strong influence in Kurdish and global literature.