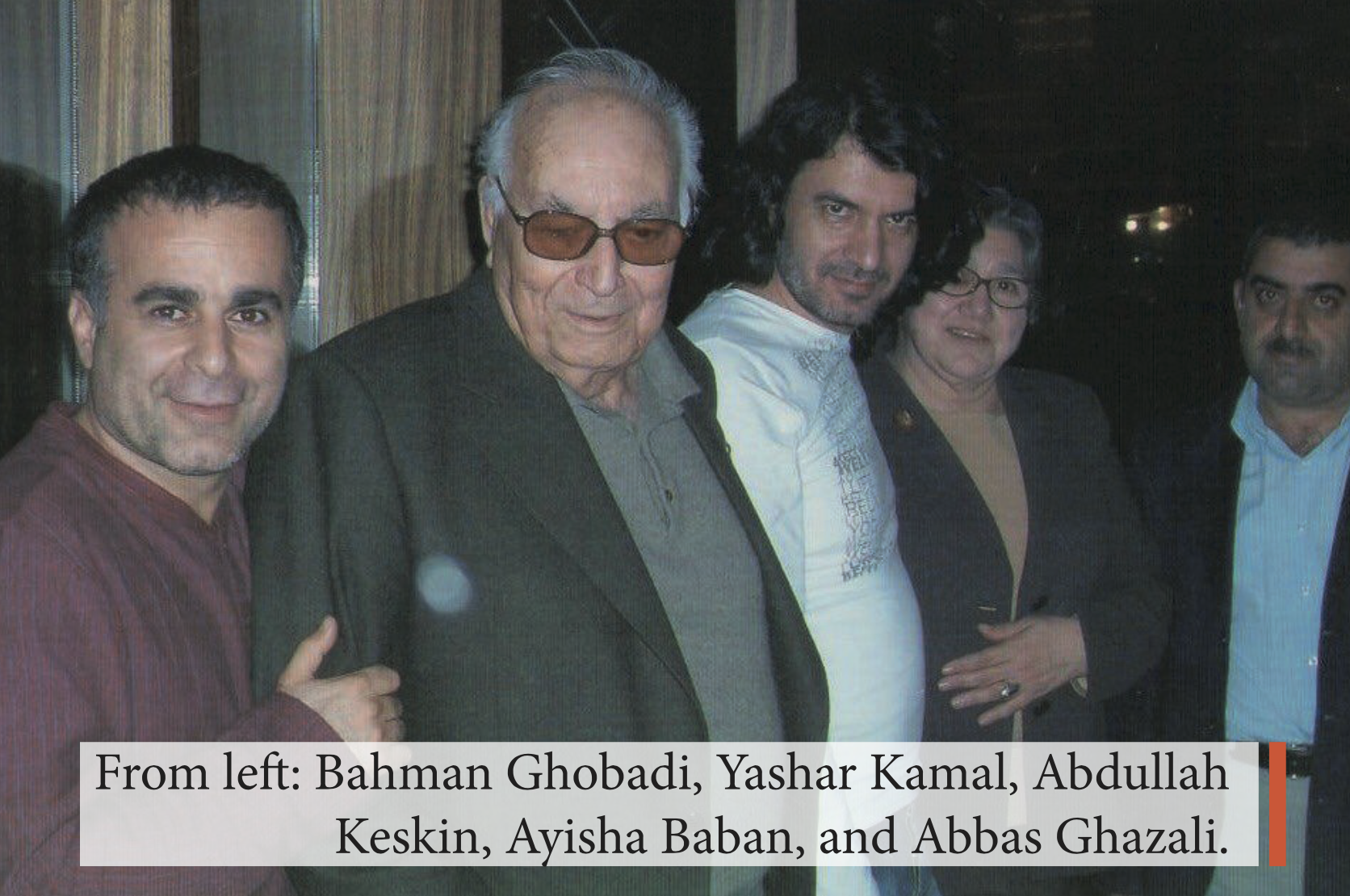

Born and raised in Nisêbîn (Mêrdîn), a Kurdish border town between Syria and Turkey, Abdullah Keskin went to study Turkology (Turkic Studies) in Ankara University, which he left shortly afterwards in 1991 for going to Istanbul and working as an editor in Welat, the first Kurdish newspaper to be published after the newly-accepted law for freedom of speech in non-Turkish languages in Turkey. After founding and working for a short period in Welat, he took part in launching Avesta Publishing House in 1995, which started to publish books in Kurdish alongside Turkish despite an actual lack of legal basis for ‘writing and publication in non-Turkish languages’. He still lives in Istanbul where he spent half his lifetime getting a great deal of important works in Kurdish and/or about Kurds printed.

You set up your publishing business at a very young age and have operated the oldest and most prominent Kurdish publishing house for nearly thirty years in Istanbul. Did you ever think that it would go like this?

No! We had no idea what would happen at the time. In 1995, when we founded Avesta, we published three books about Kurds in Turkish, all of which were subsequently banned. Following the granting of freedom of speech in Kurdish in 1991, some publications were launched, but the initial excitement and enthusiasm about Kurdish faded away as time passed. We had one aim in all that turmoil: publishing books.

There was still no recognition, while bans and other problems created by the state continued; readers, writers, publishers, all of us were self-taught, without an academic education. We were getting to know Kurdish letters and writing for the first time. Besides, the works produced in Kurdish were very problematic and not that interesting. We wanted to change that.

We started out by publishing four books in Kurdish by unknown writers – needless to say, they weren’t renowned personalities. Since we didn’t have an office, we registered a friend’s address to get a license. We had dreams like anyone else, but never great expectations. We didn’t take up this job to succeed; we just felt obliged to do it.

More than 800 titles have been published by Avesta so far, most of them in Kurdish. In your opinion, what were Avesta’s greatest achievements?

As the publishing business was only done by political groups and movements back when we started, due to the circumstances that Kurds were living through, Avesta was the first “independent” publishing house in that sense. That was a significant difference. As continuity was established, the complete works of dozens of writers were printed, which resulted in variety in many respects. We worked hard to make the books accessible and available in the market. We also have books in our store that haven’t sold out since 1996. The number of print runs for each Kurdish title has been as high as the Turkish ones, if not higher.

Think about it: we were publishing books in a language whose alphabet, even speaking it in earlier times, was banned. Publishing or broadcasting in Kurdish was also illegal before 2002. We learned many things over the last 20-30 years. Several generations came and went, always being replaced by new ones, sometimes in smaller or larger numbers. Kurdish studies are still carried out among a group of elites or intellectuals who are disconnected from the society, a reality since the advent of Kurdistan newspaper. That hasn’t changed much unfortunately, but one can say that the last 32 years starting from 1991 have been the most stable period, despite all the problems.

Kurdish studies and research, ranging from general issues to the question of “Kurds and Kurdistan”, continue to be published. Marginal themes come to light, and details surface. No one feels the need any longer to prove the existence of the Kurdish language and its history. Kurdish literature transcended the boundaries of folklore and poetry. Kurds have gotten to know themselves and to know each other. They have begun to pay attention to the other parts of Kurdistan. Cultural boundaries are being removed, and we are all heading towards a common language. Kurdish publishing houses have played an important role in these developments.

Looking back, what was your overriding motivation to pursue this profession?

We took up this profession not as a ‘job’ but as the passion of our lives. It was our whole life, and it is still so. Like someone thrown into a desert, we created everything from scratch and discovered the field on our own, since we could not benefit from the experiences of those before us. Newspapers like Kurdistan and Jîn were published here in Istanbul, but we learned about them through Stockholm 80-90 years later. We found out that it was not such a barren landscape through our struggles. Nevertheless, the release of ‘new’ works, saving them from being lost forever makes one feel excited. And, certainly, I very much love being immersed in this job.

Which parts of society were targeted and influenced by the works published? Do you think all those publications had an impact and met their objectives?

The largest segment of our readers is students. Young people comprise 60-70% of the followers of our social media accounts. However, we notice through book fairs and events that there is an older generation as well. We are also pleased that there is a growing number of women, both as writers and readers. Women make up 25% of our social media followers, and we have printed more than 100 titles by women. In addition, there is a group of readers in Turkey who have an interest in reading books about Kurds and other minorities. Researchers are also increasingly interested in our works. All in all, we can say that we have a readership from all segments of society.

You have had trouble at times distributing your publications for political reasons and faced trials. What were the reasons for that?

We publish books in a language that is characterized “a language not understood” in many legal documents. Even though publishing books in Kurdish was banned during the first seven years of my publishing career (1995-2002), Kurdish books were hardly a subject of persecution, as authorities didn’t want to “legitimize” Kurdish. If a book in a certain language is banned, it means that the language is acknowledged. Because they must find a translator for it, they must translate the texts and that translator must be confirmed by the state. Therefore, they chose to ignore Kurdish books and instead aimed at Turkish-language books. Roughly 40 books that we have published have been banned or resulted in a jail sentence or monetary fine. Courts act quite arbitrarily and according to political proclivities. However, what is worse than the obstacles created by the state are the problems in the civilian domain. Illiteracy and the language not being acknowledged by the state make the Kurdish book market smaller.

Have you ever felt like an outsider or exile in Istanbul? Do you have any other cities in mind that could rival it?

No, not at all! I don’t feel like an outsider in Istanbul. No other city makes me feel the sense of freedom that I have in this city. Istanbul is the city where Kurdish literary and cultural works were first produced. It is the Kurds’ capital city of culture. The largest portion of Kurdish population lives here. I can live feeling myself as a Kurd here much more than in Diyarbakir. Of course, it could be different if there was a Kurdish administration in the north, then perhaps one could make a comparison. It doesn’t matter if you are in a city of Kurdistan or in one of Turkey because most of the events or works are made in Istanbul.

You’re familiar with other parts of Kurdistan and publish works by authors from all regions. Reflecting on the authors and well-known personalities from all four parts, what are the similarities and differences that attract your attention in their literature and worldviews?

There are big differences. Except for a few examples, Kurdish literature is something new in the north, as they were mostly produced in the last 20 years. In the south, however, novels and short stories were published in newspapers nearly a century ago. For instance, Di Xew de (Le Xewma) by Camil Saib (1927) or Meseleya Wijdanê (Meseley Wijdan) by Ahmad Mukhtar Caf (19..) are great works both in terms of the topics and styles; they delve into social problems and even criticize society. Works by contemporary authors are powerful in a literary sense and are freer in terms of topics.

Good examples of literary works have been created in recent years, whereas we used to have more folk tales and personal accounts in the past. One of our most crucial disadvantages in the north is the language. Our connection with our language has been severed over multiple generations, and we don’t like novels much. We are short on creating very successful works in this area. We idealize society, while they criticize it.

In Turkey, the question of the Kurds has transformed over the years, taking many forms from whether they exist or not to who and what they are like. How much does the Kurdish political elite support Avesta’s prodigious cultural output and do they benefit from it to strengthen their arguments for the political struggle in Turkey?

Turkish has now become a language in which the greatest number of books about Kurds are published. Although there are remarkable efforts to write studies in Kurdish in recent years, it is still incomparable to Turkish in terms of the number of titles and print runs. Important books are translated into Turkish, which has made Turkish a significant resource for Kurdish studies. Some official organizations in Turkey, along with academics, researchers and journalists make use of these works, but the political discourse of Kurdish politicians is gradually distancing itself from the ‘national issue’.

Having published so many works on Kurdish history, culture, and identity, what do you think are the differences between the Kurds of today and past? At which points did Kurds succeed and when did they fail?

Knowledge is critical and as sacred books point it, saying preceded everything; in other words, everything started by saying. Former generations made significant efforts, laying strong foundations but they didn’t last. The period from 1991 to today is the longest and most stable period. A wide range of literature was formed in many fields. With few but strenuous efforts, Kurdish cultural and intellectual heritage was collected. However, instead of intensifying Kurds’ will for their rights, it has decreased. We had larger goals when we had less knowledge about our society, country, and culture. We have more knowledge of ourselves and our surroundings now, but our goals and understanding are weaker than before. We will see if this is something temporary or permanent.

On the other hand, earlier Kurdish discourse was meant to convince Turks, and some sort, albeit incomplete, progress was achieved in that regard. But now, we are forced to put forward arguments that should have been advanced thirty years ago, and we notice that a discourse of arguing why something or another is unnecessary for Kurds is starting to take hold. This, in turn, makes convincing Kurds, who are political actors themselves, even more difficult than convincing Turks. It seems that the ‘Kurdish question’ has now turned into an intra-Kurdish question.

At the beginning of the 21st century, it was widely argued by northern Kurds and those in Turkey that this will be a century that favors the Kurds. Almost a quarter of this century has passed and there are many complaints about what Kurds are currently going through. Do you think that it was a sheer demagogy then or there was a real likelihood for those views to be realized?

Yes, there was such an opportunity, and it did materialize to a certain degree, but it could have turned out better. Having reached the 21st century and survived the previous ones is a historic success. Travelers, missionaries and diplomats who were writing 150-200 years ago argued that the Kurdish people and their language had 20-30 years left to exist, but the Kurds and Kurdistan survived centuries more.

The danger of extinction today is far smaller than in the past, as anyone can save many things from being lost with a little effort. Nevertheless, we are facing huge problems. Kurdish studies are still carried out by a tiny group of elites, which cannot reach society; at the same time, society itself doesn’t care much about these works. Failure, for us, is not that we are going backwards; the ominous indicator now is that we take 3-4 steps forward and then just turn around and go back, whereas we could have taken ten steps forward. Some matters should be fixed and settled more quickly now, such as Kurdish education and making Kurdish an official language. If these aren’t achieved, the Kurdish language has a great risk of being lost, and if the language is lost or used very little, Kurdayetî (the Kurdish cause) no longer makes sense.

Why do you think a constant rhetoric of grievance is dominant in Kurdish political discourse in Turkey, where the largest Kurdish population resides? Is it because the circumstances disfavor them, or are Kurds incapable of changing the circumstances in their favor?

You must have noticed the word ‘heqîqet’ (reality/righteousness) is being used widely in the Kurds speeches and discourse in Turkey nowadays. ‘Absolute righteousness’, like many other things, does not allow for different thoughts to emerge and compete. In her memoir recently translated into Kurdish, Golda Meir says, “I have only one thing that I wish I can see before my death: I wish my people won’t be in need of mercy.”

This rhetoric is outdated now, and it must change; it creates more harm than good. The more powerful that the Kurdish movements became, the more their national discourse weakened, and their aims and expectations grew smaller. The view that “all the world has betrayed us” has become a custom among developing nations. I don’t think these ideas gain much traction in international affairs. Look at us, for example. Nearly the whole world from the United States to Europe is striving to unite Kurds in the south and the west and making efforts to negotiate with us as a nation or state, not as a party; however, our situation is evident. Despite not being entirely independent, we have more internal conflicts than external ones. Kurds have never had fewer obstacles in their history, and we certainly face fewer struggles than Kurds in the past.

People have great expectations from the coming elections. You have witnessed many elections in your lifetime. What makes this one more significant than from previous ones? Do you agree that it might have dramatic results for Kurds?

As a Kurd who lives in Istanbul, I also want this administration to change. They have governed for more than 20 years – it is enough. The Kurdish question is now an issue with the state, not with political parties. No one can do anything without an entire agreement. I am not very hopeful about the opposition, as they don’t say anything concrete. They could be worse for the Kurdish question than the current administration. The Kurdish vote is important, but it benefits everyone except for the Kurds themselves. They have helped the opposition win so many municipalities, but what has it accomplished for them? Therefore, I don’t prefer that the Kurds take a side nonsensically with anyone on intra-Turkish issues. Turkish society is a ‘conservative’ society in general, and Kurds don’t need to make them their foes. Kurdish politicians need to make use of the art of politics and prioritize their people’s interests.

If you had to assess Kurds’ performance in all fields of arts, which ones would you mark as ones in which the Kurds remain behind and in which ones do they show promise?

It varies according to different parts of Kurdistan. I can see that the art of cinema is flourishing in all parts over the last 10-15 years. Kurds don’t have movie theaters, but they have movies. In the south and east there are more research studies, especially in the field of history, and they have a more vibrant literature. We could also add the west (Rojava) to our list of Kurmancî literature. They are not as disconnected from their language as we are. We are listless and impatient here in the north, where we are better in poetry and short stories. And lastly, in all the other three parts, they are better than us at painting and sculpture.

You love Kurdish foods very much. What are your thoughts on Kurdish cuisine?

I am very curious about gastronomy in general. I am open to different tastes and do my best to get to know other cuisines. However, our dishes have remained unchanged, like many other things. Of course, there is a good side to that – it is more authentic – but one has to try new things as well. If one was to evaluate our cuisine regarding all its different parts and regions and cultures, it is probably richer than those of several countries put together. It is not exhibited though. You have few options in the restaurants, since our cities are not as developed. I bring plants, vegetables, and other stuff from many places and try different things with them. When I am bored, I turn to cooking. For instance, I tried to make bulgur and rice with lentils and gulik (a plant) and added shrimp to it. The result was great.

Ciwanmerd Kulek is a writer and translator based in Diyarbakir. He has a degree in English Language Teaching. He is the author of several novels and short story books in Kurdish, and has translated a dozen of works from the world literature into Kurdish.