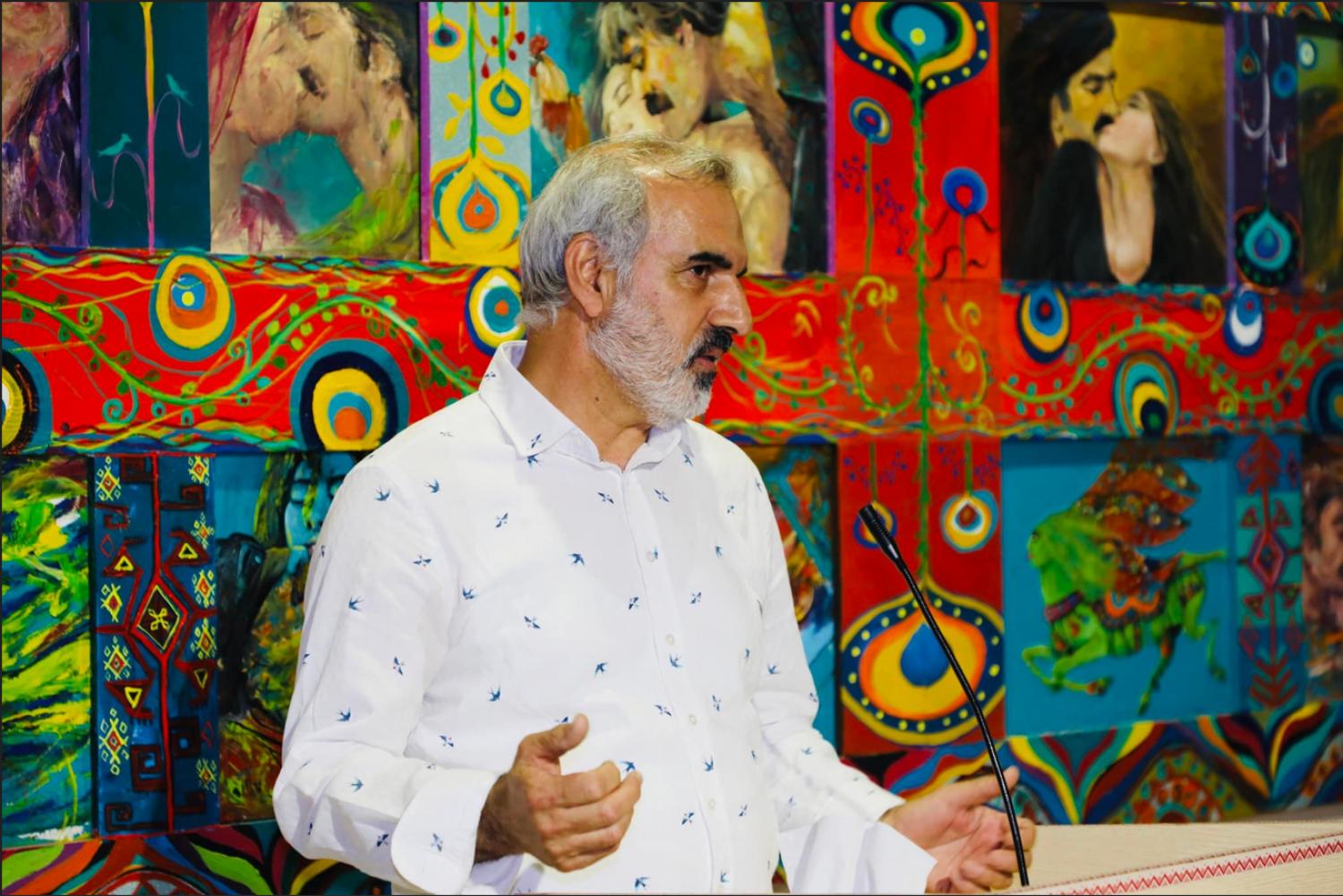

Rostam Aghala in His Words

Born in 1969 in Koya, Kurdistan Region - Iraq; Graduated in 1989 from Institute of Fine Arts, Sulemani; Director of Zamwa Gallery for 12 years.

Aghala’s Key National Exhibitions

1989- First Successful Show at Media Gallery Hawler Kurdistan (shown 500 Paintings).

1992- Show at Sulemani and Koya.

1994- Show in this year at Sulemani.

1995- Show in Media Hall, Hawler.

1996- Show in Sulemani Hall (Daboka).

2008- A show in Germany Consulate Gallery.

2013- Private Exhibition American Consulate in Erbil.

2018- Private Exhibition in Suleimani.

2018- Construction and Opening of the Aghala Museum in Koya (took nine years). 2020- Private Exhibition in Erbil Hotel Divan.

2022- Private Exhibition American Consulate in Erbil.

Ibuilt a wall between people and me. Not because I want to get away from society, but because I want to enjoy my paintings. I found my deepest personality in paintings and felt my deepest pain in art. In the midst of this art, I was torn to pieces. Millions of people live and die like cows and sheep without leaving skins to make cosmetics or shoes.

I want to be a cow, I want to be a sheep, whether I like it or not. Sometimes I feel like a donkey because I have to carry my stuff and set it up over and over again. For 35 years, I have been painting non-stop without thinking about what I am doing, why or how I am painting. Now that I’ve established my own style, I feel like I’ve come to the point where I don’t have to be told not to draw in my own way. Whenever students who want to study art are asked how many Kurdish painters they know, most mention my name, Rostam Aghala.

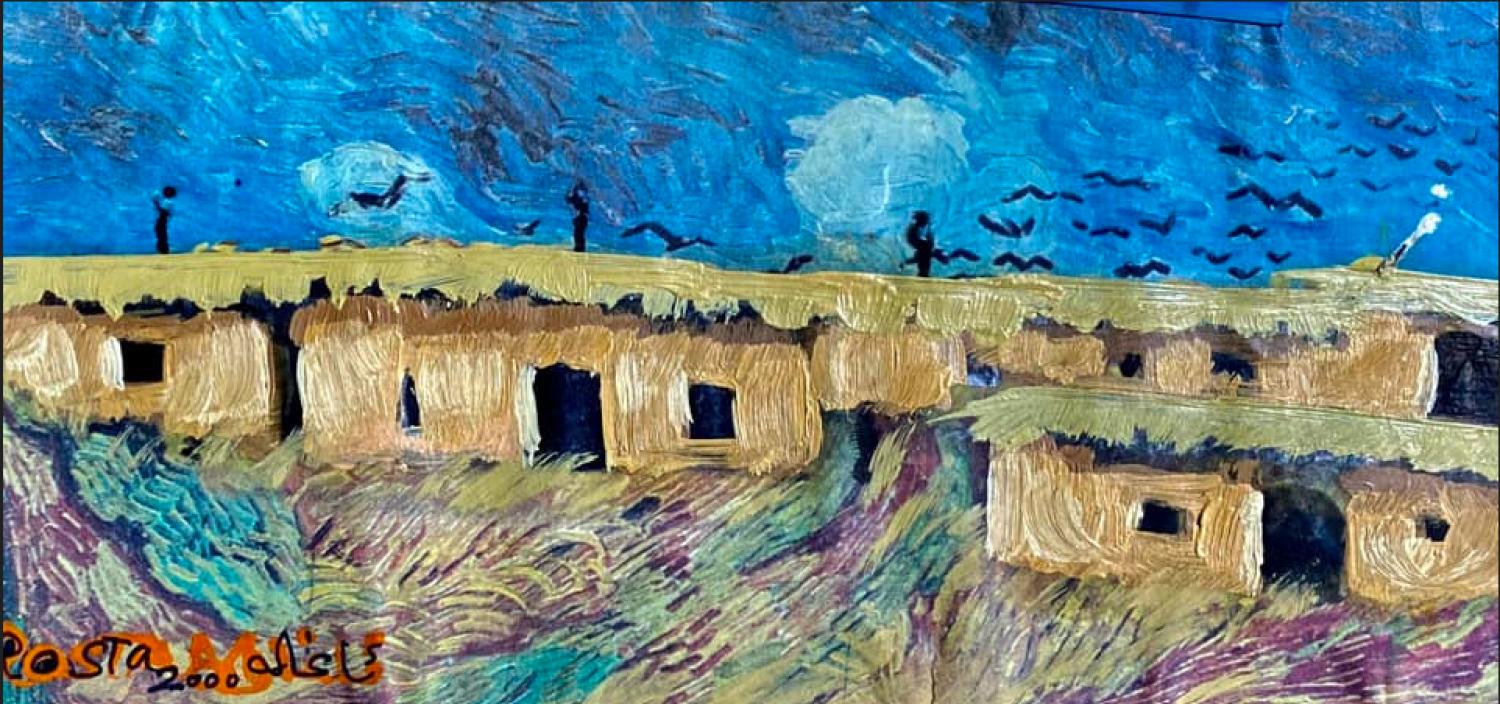

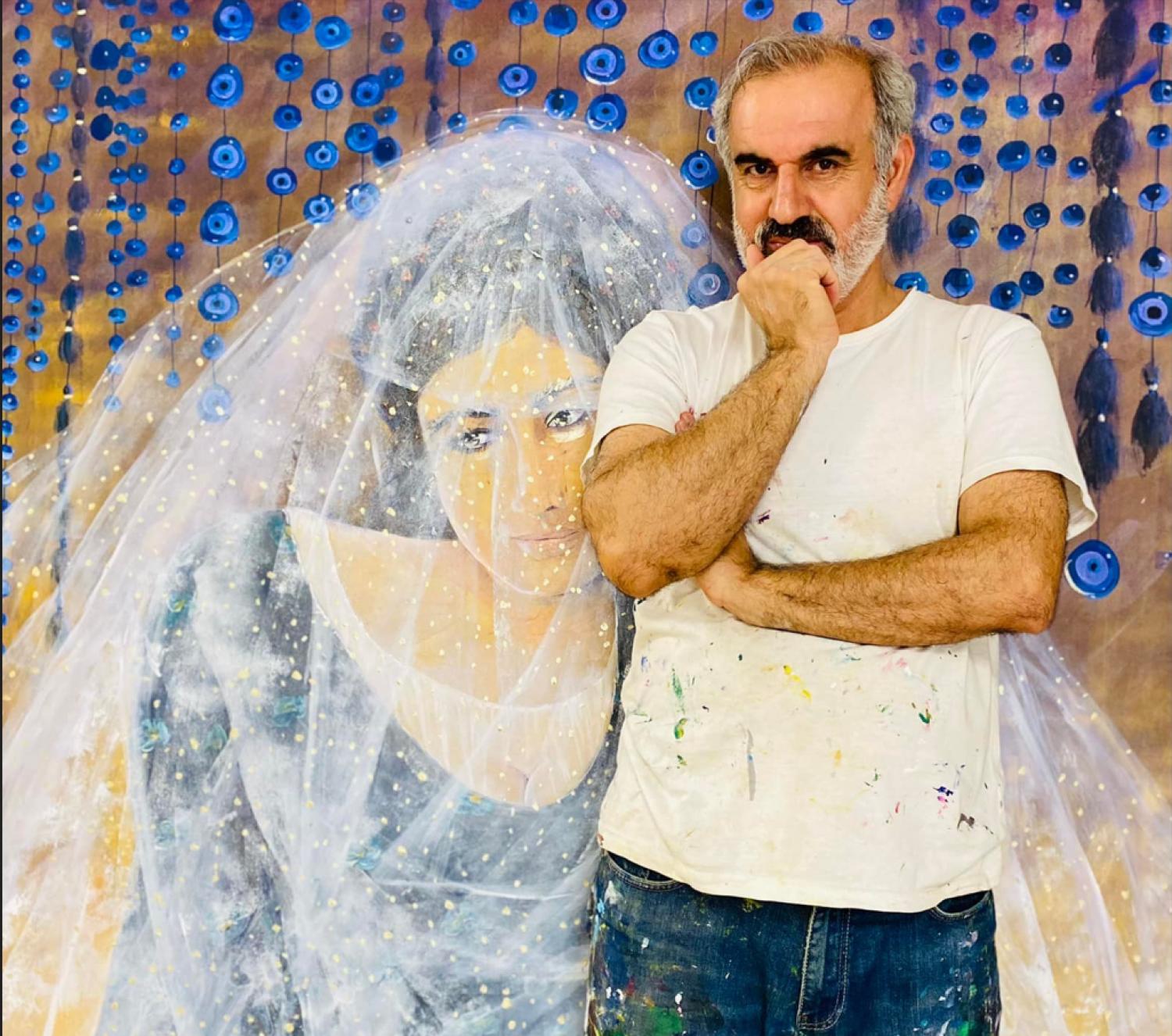

My art is a carrier of national identity and human suffering in a Kurdish form, and I have painted with highly classical European techniques. The subjects of my paintings are broken, angry, and lonely Kurdish personalities. Trees in my paintings and people and birds are alive, dying, and going away. Nestless birds and burnt nests occupy a large space in my paintings.

In dozens of my paintings, the donkey struggles with humans and creates civilization. It is no wonder that I am the only artist in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq to have my own museum to exhibit my art in Iraq. The museum is unprecedented in Iraq.

My paintings are attracting the highest prices in Kurdistan. Now, it is time to open the doorsof museums and galleries so that I can exhibit my paintings. My goal is to showcase my art asa Kurdish artist in the world because my art is comparable with the best artists in the world. I want to show the pain of my soul and nation to the eyes and feelings of the people of the world. Then I want to sell my paintings at a higher price in Kurdistan.

There are numerous articles written about me, but I find them weak and focused on describing themselves while ignoring my feeling and techniques. Therefore, I am not going to repeat what has been written about me. I am not intending to write on Kurdish art, or methods of plastic art at the cost of my art.

My level of experience is at a stage where I do not care when and what to draw. I am not very much focused on which artistic theory to follow. I am also not that busy minded to search for various types of material techniques to draw a tableau but am more focused on the composition of the drawing. For me, technique and material are not the sole parts of art.

I very much realize that if I throw my realistic figures in front of my tableaus or throw them away, they get much closer to becoming more global, although I also understand the opposite side.

My drawings are not documentaries for the sake of beauty. I have not drawn for public morale or at the request of anyone. My work has always been the result of reactions, playing with and defending the eruption of my emotional moments and instability be it intended or not. Before describing my work as beautiful, harmonious, or successful, they are telling neck-breaking stories of failure, pains, and dissatisfaction. These are the key factors behind them.

We the artists, when we reject each other as persons, belittle each other’s methods. If we just look around, we realize that our audience accepts our work, and the public writes and reads about us.

Each of those famous people whom we consider as our pioneers had their own different method.

If I realize that my audiences are no more interested in my work and do not like my method, I will refrain from showing my art and try to prevent them from knowing about my art, as I will need to make that decision and conclude that I had had enough of that method and was indirectly told so.

I am not Kandinsky in trying to extract the figures of my tableau. This does not mean that I am not trying or feeling modern. Oftentimes, modern work kills the personality.

Culturally, I would like to use modern forms to benefit from other nations’ cultures. If we look at modern artists, they have benefited from cultures beyond Europe. In Chinese and Japanese graphics, for example, they have used skeletons from Picasso’s and Braque’s worlds to provide color to the last moments of their lives - colors were their main work. I do not know when form leaves my work. Sometimes I use color for creating a form.

In Kurdish Fine Arts, our classical and modern art examples lie behind that history. We are growing on a digital stage, which is why our stages are empty and without results. They are all mixed but easy to separate. They are quite similar. We are at the stage of growing and ending.

“To graduate from the Institute of Fine Arts, Rostam was asked to present a copy of a masterpiece. In an Iraqi magazine, he had seen a reproduction of a painting he instantly admired called Love. Without knowing the name of the artist, Rostam proceeded to painstakingly reproduce the image and present his work, which was rejected on the pretext that the artist was “not a great master.

“Years later, a foreign journalist gave Rostam a book about the work of Gustav Klimt and, only then did Rostam discover the identity of the painter whom he had copied for his graduation project.”

Chris KutscheraFrench journalist, researcher, writer and specialist on the Middle East, with particular interest focused on Kurdish national movements.

Early in the 1990s, I tried hard to modernize my work. In the 1980s, when I was a student at the Institute of Fine Arts in Sulemani, I was trying irregular work. For example, I was using a wide piece of fine wood instead of a brush for painting my canvases. For the Halabja massacre, I opened an exhibition in one of the rooms at night in my dormitory in the Sarkarez. This building was destroyed and burned by an illiterate housekeeper burning six tires.

I also helped clean Koya’s old shopping area, which was closed for 35 years. It took me two months to clean that place, which was located downtown. I found that initiative important and considered it as art, where I discovered myself through changing the past and introducing today’s art.

In the 1990s, I considered goodwill initiatives, findings, and reminiscences about the past as art. Also, I considered all the hardships that I had faced in cleaning the abandoned shopping area as determination. This does not mean that I am remorseful for what I did, but I will not do it again. That piece of work gave me a lot.

The first inauguration of the shop in that town coincided with the inauguration of the first elected government in the Kurdistan Region in 1992. Now instead of cleaning an old shopping area to have an exhibition, I am building a gallery in Koya similar to it.

In 1993 I collected old and rusty oil ‘Raay’ cans from a neighborhood and brought them to the main busy street in Koya, despite a lack of interest or moral and material support. That type of work became a new method in all Kurdistan. As a result of that project, I was named ‘Rostam Qody,’ which translates to ‘Rostam the can man’.

If I slightly reflect on my past, starting from the time when I was a student at the Institute of Fine Arts, I feel I did some unacceptable work.

I do not forget the summer days of my childhood when I was working on the streets in ‘Shawker Village’. Those three months I was missing the town. On the hot plains, I was listening to the sound of passing cars. Or from the top of Haibat Sultan mountain, I was watching the shining reflections of car screens, which was giving me a nice feeling that I was going back to town.

In the summer of 1980, when I was a student at the Institute of Fine Arts, I was selling farmer’s hats in Sari Razh, Sulemani, Baghdad, Pirdê, and many other cities and towns across the country. I do not forget the summer of 1986 when my brother Kamal and I were working on sunflower farms in the Sarwchawa area. That was the most difficult experience of my life.

The images of that difficult experience and life during those periods have become the soul of many of my tableaus. But this does not mean that I am sharp in retaining memories.