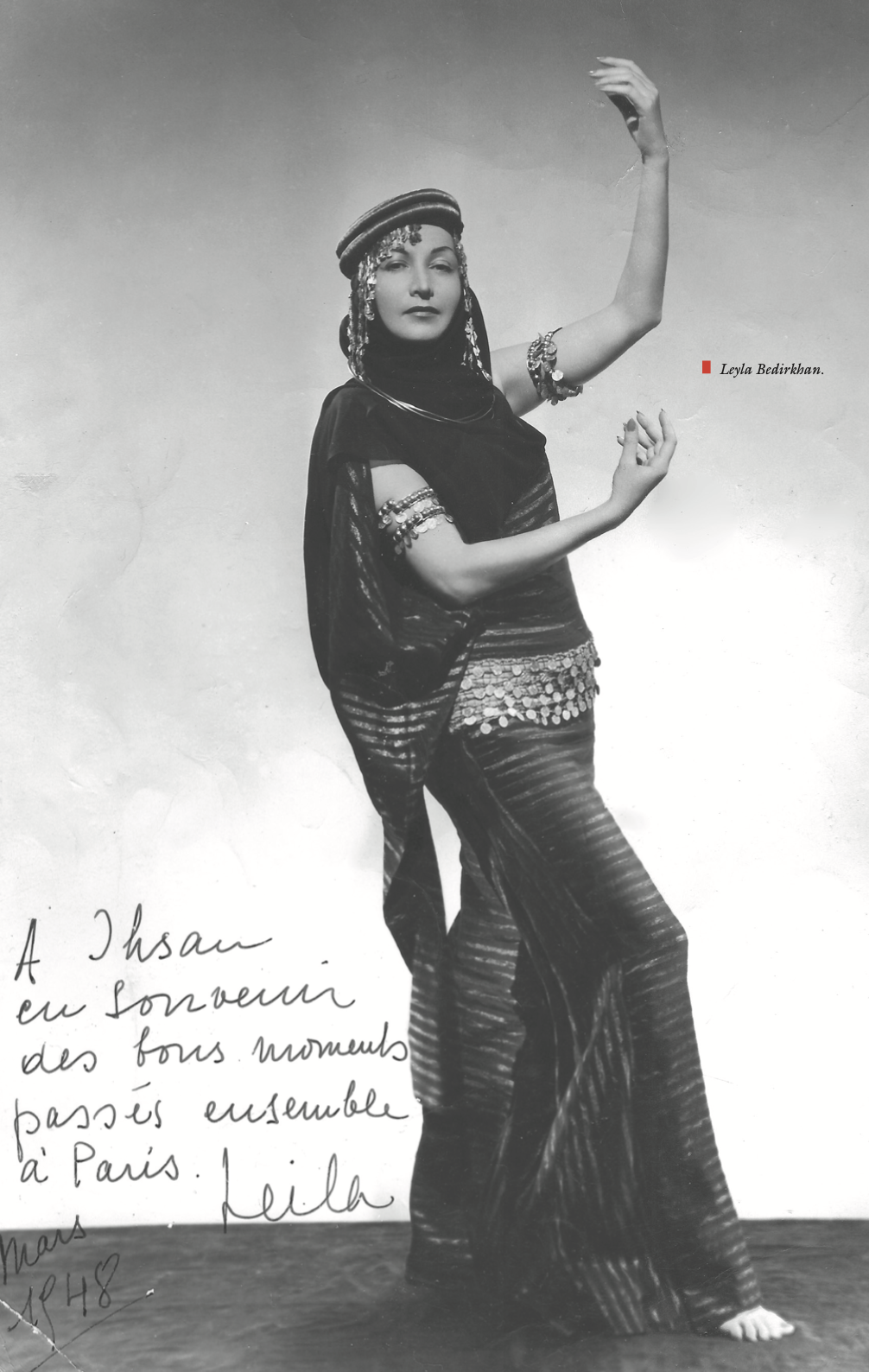

“I am the first Kurd to dance at La Scala [Opera House in Milan]. When I was asked, ‘Are you a woman from the East?’ – especially regarding Egypt, a country where I spent part of my childhood – nothing there felt foreign to me. But if your question implies, ‘Are you an odalisque?’ then know that only my dance is oriental; I am not myself oriental.”

–– Leyla Bedir Khan

Reading women’s narratives leads to a historiographical paradox between the past, which has been constructed by tradition, and the future, which is shaped by readers who impose their own ideologies that may obscure the original traces of historical incidents. The subject of women, dance, and modernity thus invites challenges. It becomes essential to unravel history and explore the concepts of gender as they relate to body movements, which often defied social conventions.

Leyla Bedir Khan, the first Kurdish dancer to perform at La Scala Opera House in Milan, was born in Istanbul. Although her birth date is disputed, with sources suggesting either 1903 or 1908, her lineage is clear: she came from a distinguished family. Her father, Abdurrezzak Bedir Khan, was a notable diplomat, and her mother, Henriette Ornik, was an Austrian-Jewish dentist. Her family’s background highlights significant historical and political dimensions. As Ottoman Kurds, her ancestors long coexisted with Turkic peoples starting from the early Abbasid era and established official ties with the Ottoman Empire following the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 – a pivotal moment in the conflict between the Ottomans and the Persian Safavids.

The dilemma of modernity and gender

The topic of identity and liberty becomes particularly complex when considering Bedir Khan – a Kurdish woman shaped by political and cultural conflicts. During the early twentieth century, according to scholar Zharmukhamed Zardykhan in his 2006 article in Middle Eastern Studies titled “Ottoman Kurds of the First World War Era,” Kurds played a significant role in World War I and the Turkish War of Liberation, affecting the destinies of the Ottoman Empire, Tsarist Russia, and the nascent Turkish Republic.

Globally, after World War II, women’s lives in developed countries transformed dramatically: household technologies reduced the demands of domestic labor, life expectancies rose, and the expansion of the service sector created new professional opportunities that required less physical strength.

Against this backdrop, Bedir Khan’s identity was doubly constructed – by both nationality and gender – illustrating the concept of intersectionality. Her position highlights Zardykhan’s concept of how Kurdish cultural conflict intertwined with gender issues, complicating any straightforward understanding of modern identity.

Philosophically, this raises important questions about how women were perceived during the Ottoman era and the roles Kurdish women occupied within that context. The challenges that Bedir Khan faced and the transformations she underwent concerning race and gender offer significant insights into unraveling the complexities of historiography.

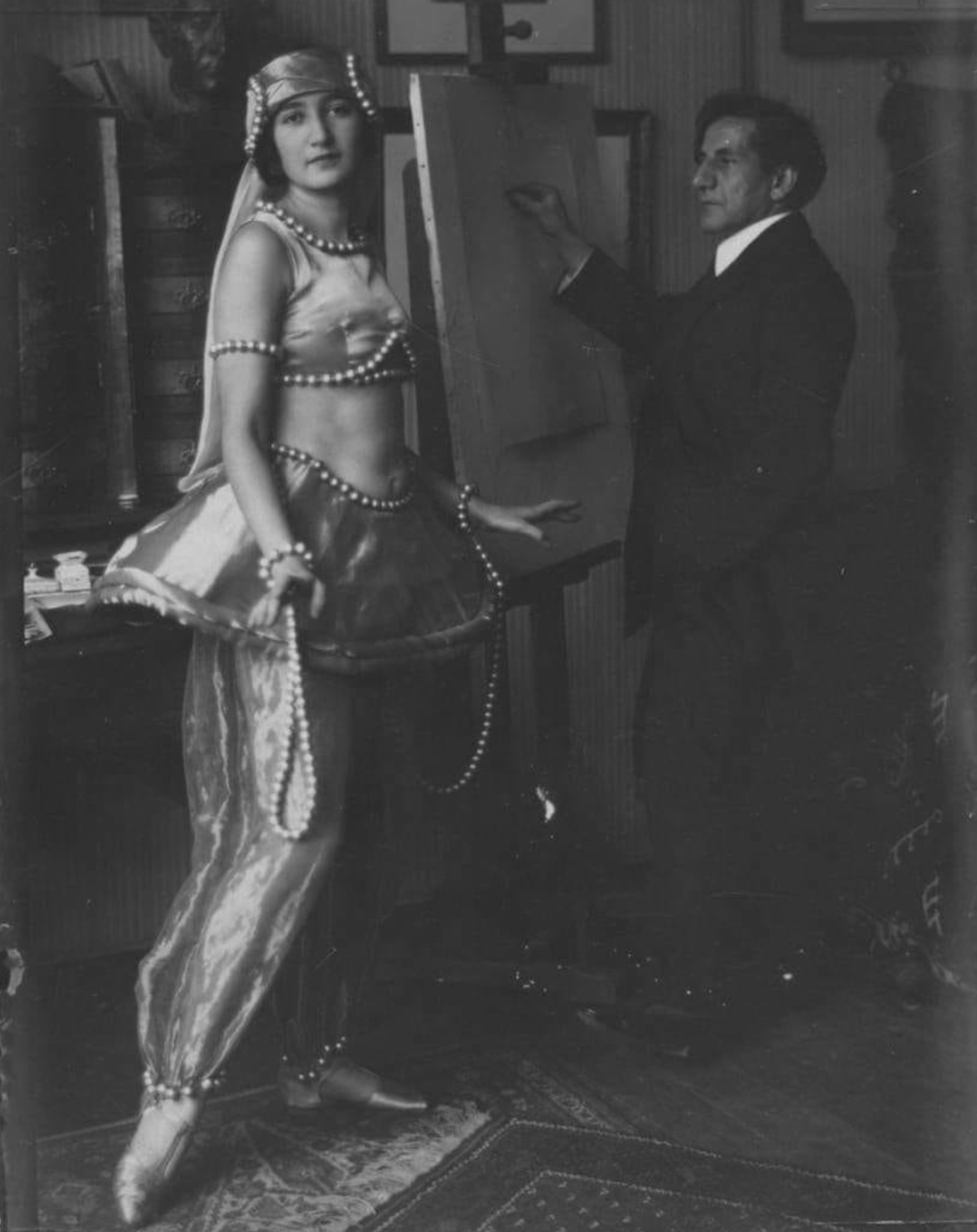

Bedir Khan’s early years were shaped by significant upheaval, including a 1913 decree calling for her family’s extermination, which compelled their forced migration to Egypt. Despite these challenges, she thrived in Egypt and pursued studies in music and medicine in Switzerland. Her dance career took flight after World War I with her ground-breaking performances in Vienna, blending Indo-Aryan and Middle Eastern influences. She then gained acclaim across Austria, the United States, and Italy, showcasing her talents and introducing original choreography.

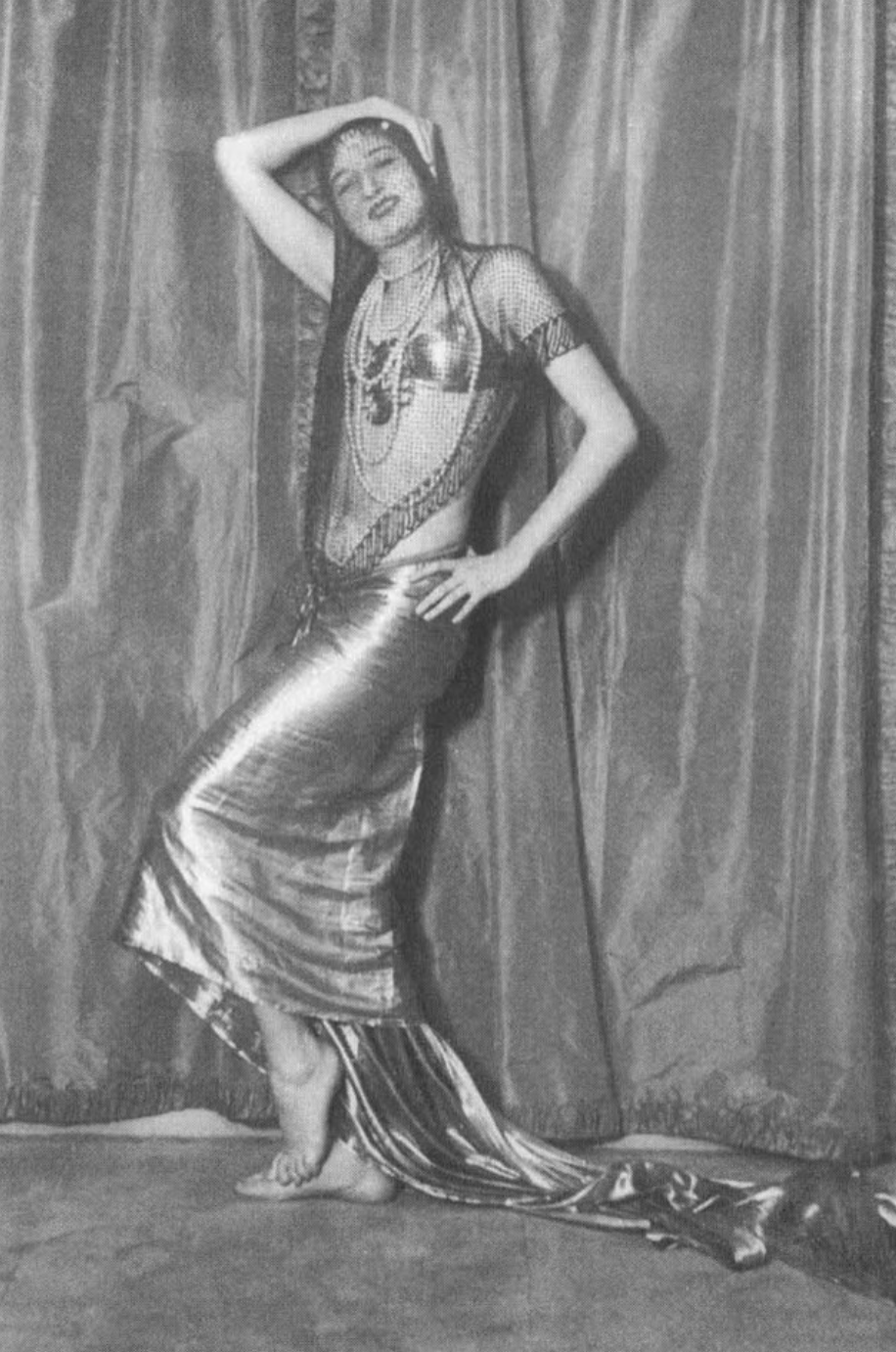

Furthering her ballet training in Germany, she performed at prestigious venues like La Scala, captivating audiences worldwide. Although recognized for her ‘exotic’ role in Belkis, Reine de Saba (Belkis, Queen of Sheba), she primarily showcased original choreography inspired by Assyrian and Egyptian traditions. She even staged performances in authentic locations, including a memorable exhibition at the Great Sphinx in Egypt.

Eventually, her path led her to Paris, where she established a dance school and continued her legacy until her passing in 1986.

Challenging orientalism

Bedir Khan’s work is fascinating for how it challenges orientalist conceptions. While she described her dance as oriental, she explicitly denied being oriental herself. On one level, this reflects her assertation that she did not want to embody the stereotypes projected onto Eastern women. More profoundly, it inverts the traditional image of the Eastern woman as a passive, exoticized subaltern.

The irony – being viewed as oriental while resisting its essentializing gaze – mirrors modernity’s challenge to constructed social ideologies. Through her dance and life, then, Bedir Khan both embodied and resisted the narratives imposed upon her, carving out a space for autonomy, creativity, and cultural fusion.

Shajwan Nariman Fatah holds a Master’s degree in English Language and Literature from Near East University, Cyprus. She currently serves as head of the Department for Gender Studies at Charmo Center for Research, Training, and Consultancy.

Editor’s Note: This article was mistakenly published under the wrong byline in the print edition of Kurdistan Chronicle’s Issue 25. While we sincerely apologize for the error, the digital version of the article is published here under the correct byline.