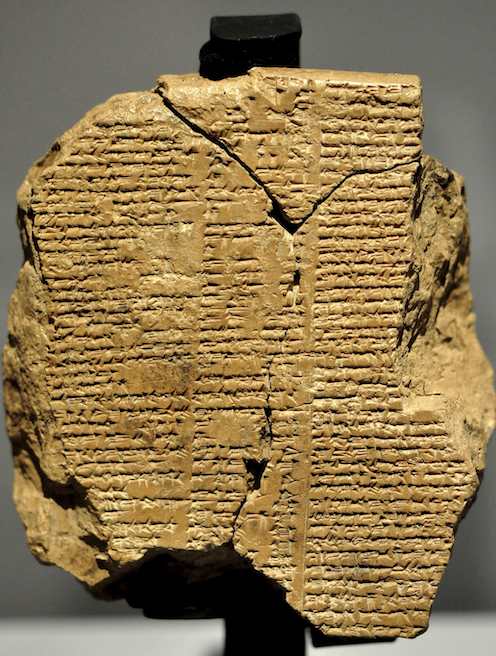

Estimated to have been written between 2100 and 1200 BC, the Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest poetic histories to be passed down to today. The story was first documented through the excavations of British archaeologists in the 1850s, who unearthed 15,000 fragments of Assyrian cuneiform tablets in Nineveh, the site of the Royal Library of the 7th century BC Assyrian King Ashurbanipal. These fragments were then compiled and translated in the 1870s, helping to bring the epic to light.

The tablets in Ashurbanipal’s library also contained tablets in many other languages, making it an invaluable source for learning about the beliefs of our distant ancestors. The Epic of Gilgamesh relates the adventures of the king of the city of Uruk, Gilgamesh, who is thought to date to the Third Dynasty of Ur. Described as “two-thirds god and one-third man,” the king possessed power and beauty beyond that of any other human, making him the perfect protagonist for this timeless story.

These elements and more inspired Kurdish filmmaker Karzan Kardozi to return from the United States to Kurdistan in 2022 to create a visual adaptation for a modern audience called Where is Gilgamesh? Despite a limited budget, the dedication and hard work of Kardozi and a team of five brought the movie to fruition, presenting this epic tale to a new generation of film goers.

A modern crime story

In what critics describe as film noire, Kardozi centers the story around the heist of the tablet of Gilgamesh from a museum. The film begins with the mother of the main character Govan seeking assistance from Haji Hazo, a mullah who specializes in exorcisms and crafting talismans based on Islamic traditions. Concerned about her son, who works as a museum guard, she requests a talisman to help him get married, sharing personal details about him with Hazo.

Govan’s life is then turned upside down by an anonymous telephone caller, who demands that he steal the table in exchange for his now kidnapped mother. He proceeds successfully in the operation but enjoins his friend Akam to accompany him when he meets the dangerous gang for the handoff. The leader of the gang turns out to be Hazo, and Govan receives a beating for bringing Akam with him, while the gang disappears with the tablet.

The film narrative then shifts to Govan’s new determination to return the tablet to its rightful place. When he and Akam go to confront Hazo, a clash results in Hazo’s death, forcing the friends to flee the city, which, in turn, results in Akam’s death. Govan also learns that Hazo had been acting under the orders of his boss, Aveen, and her father, who become the focus of his new quest. On the run again, Govan encounters a truck driver who offers him comfort and wisdom, saying “everyone searches for something, but few of them find it.” Despite these words of warning, Govan continues, unaware of what fate has in store for him.

Connecting the dots

While there are major differences between the film and the original epic, the film’s plotlines contain distinct elements of the Epic of Gilgamesh. For instance, the opening scene draws a parallel to the moment when Gilgamesh’s mother, Ninsun, seeks the protection of Shamash, the ancient Mesopotamian sun god, for her son as he embarks on his journey to confront Humbaba – the fearsome guardian of the forest where no human being should enter. In the film, the role of Humbaba is assumed by a character named Haji Hazo, a businessman operating in the black market, symbolizing a place forbidden to the ordinary person.

Character development provides a source of rich parallels between the epic and the film. In the epic, Gilgamesh is on a quest for immortality and seeks to revive his dear friend, Enkidu, while Govan seeks both the lost tablet and vengeance for the death of his friend Akam. Meanwhile, Enkidu lives among the animals in the forest, and Akam is portrayed as living on a farm. Finally, in the epic, Enkidu’s life is taken by the gods Ishtar and Enlil, both divine gods of immense power – roles that are mirrored in the film by Aveen and her father, who similarly hold the fate of others in their hands.

The film also builds parallels the narrative outline of the epic. For instance, Gilgamesh mentions visiting the underworld or diving into the depths of the sea to secure his wish of immortality, and Govan similarly enters the sewers in pursuit of his goal. Also, in the epic, Gilgamesh encounters Urshanabi, an ordinary man granted immortality by the gods, who advises Gilgamesh to return to his kingdom and cherish what he has. In the film, this advisory role is fulfilled by the truck driver who counsels Govan after picking him up.

Timeless themes in a contemporary context

Kardozi also emphasizes that the Epic of Gilgamesh delves into universal themes, such as human connections, ethical values, common fears, and existential questions.

The film reflects these themes by bringing them into a modern context, particularly highlighting a pressing issue in the Middle East: the undervaluation of historical artifacts. Many of these treasures are relegated to private collections and subsequently forgotten, a metaphor for the region’s disregard of its cultural heritage. Additionally, the film touches on themes of friendship, the meaning of life, and the complex interplay between good and evil, demonstrating its alignment with the timeless concerns explored in the ancient narrative.

The film’s length – which is slightly shorter than most films at 90 minutes – necessitates the loss of some contextual elements, making certain scenes challenging to interpret. Fortunately, our questions were answered in an interview by Kurdistan Chronicle with the filmmaker, offering deeper insight into the intended narrative.

For instance, after Akam’s death, Govan drives off, and a peaceful image of an island with birds and a beach appears, only to be abruptly destroyed by a nuclear explosion as Aveen’s face emerges. This sequence visually conveys Govan’s emotional turmoil, his initial calm – as represented by the tranquil island – is suddenly shattered by explosive rage.

The writer’s portrayal of Govan’s psychological transformation mirrors the awakening and shift in perspective experienced by Gilgamesh. While Gilgamesh returns from his journey wiser, Govan gradually loses his sanity. Karzan made this choice to portray how the modern individual is constantly hustling, while bringing to life the yearning inside us for the peace of simpler times. This idea is portrayed in the simple scene of Govan being pushed into his grave, from which he rises as a different person.

Filming obstacles

During our interview, Kardozi confirmed that the initial cut was three hours long, but that the film was shortened to one and a half hours for screening in Erbil cinemas. “No cinema in Kurdistan would run a movie that was three hours long,” he admitted.

Another major obstacle for Kardozi was a small budget, which meant limited opportunities for retakes or rehearsals and insufficient equipment. However, Kardozi underscored that working with his team was immensely enjoyable, and they managed to overcome many challenges with creativity. For instance, when professional lighting equipment was unavailable, they made use of natural light and customized LED lights for certain scenes. “The Sony camera we used was of the lowest quality, so we had to use three different lenses to make adjustments,” Kardozi noted.

Another issue was time constraints at filming locations. “We could only use the museum between 9:00 am and 11:00 am or 12:00 am, which forced us to rush while filming,” he explained. Additionally, Kardozi was responsible for all post-production work – including editing, creating the movie posters, and producing the trailer – as the budget did not allow for hiring additional staff. “I had to do it. It needs to be done if you want to create a movie independently,” he stated.

Despite these challenges, some of his favorite moments in the film came from improvised elements. Kardozi highlighted the final shot featuring children, in which one of them looks down at a skull and says, “This is immortality.”

Another improvised moment occurred when construction workers continued working during filming, adding a natural touch that reinforced one of the film’s central themes – that life continues, even amid violence and suffering. “In broad daylight, one of the characters was being tortured while others were simply going about their work,” Kardozi reflected.

Ultimately, Kardozi sees this film as a learning opportunity. Before concluding the interview, he hinted that his next project would focus on the relationships of five individuals, allowing him to delve deeper into the interpersonal dynamics of his characters.

Kaveen Shkearvan is an interpreter and translator based in Erbil, the Kurdistan Region.