Imagine stepping back in time to the dawn of agriculture, when the first seeds of farming were sown. This is the story of Bestansur, a unique archaeological gem nestled in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains in Kurdistan on the edge of the Shahrizor Plain.

Roughly 30 kilometers southeast of the city of Sulaymaniyah, Bestansur is a Neolithic settlement and the first and only archaeological site to present the earliest stages of village life in the region. The site is of global cultural, historical, and archaeological significance as it provides the first evidence of human civilization in Kurdistan for the period 8000-7100 BC.

The site consists of a series of mud brick buildings that were erected during a great transition period spanning nearly one thousand years. Thousands of stone, clay, and bone artifacts have been unearthed within the buildings, as have human burials under the plaster floors of one of the buildings, and traces of red-painted plaster on the walls.

A decade of digging

A joint Iraqi-UK team started excavating at Bestansur in 2012, and the project operates under a memorandum of understanding with the Sulaymaniyah and Erbil Directorates of Antiquities and Heritage and with agreement from the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage in Baghdad. The project is undertaken in full collaboration with the Director of the Sulaymaniyah Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage Kamal Rasheed Raheem.

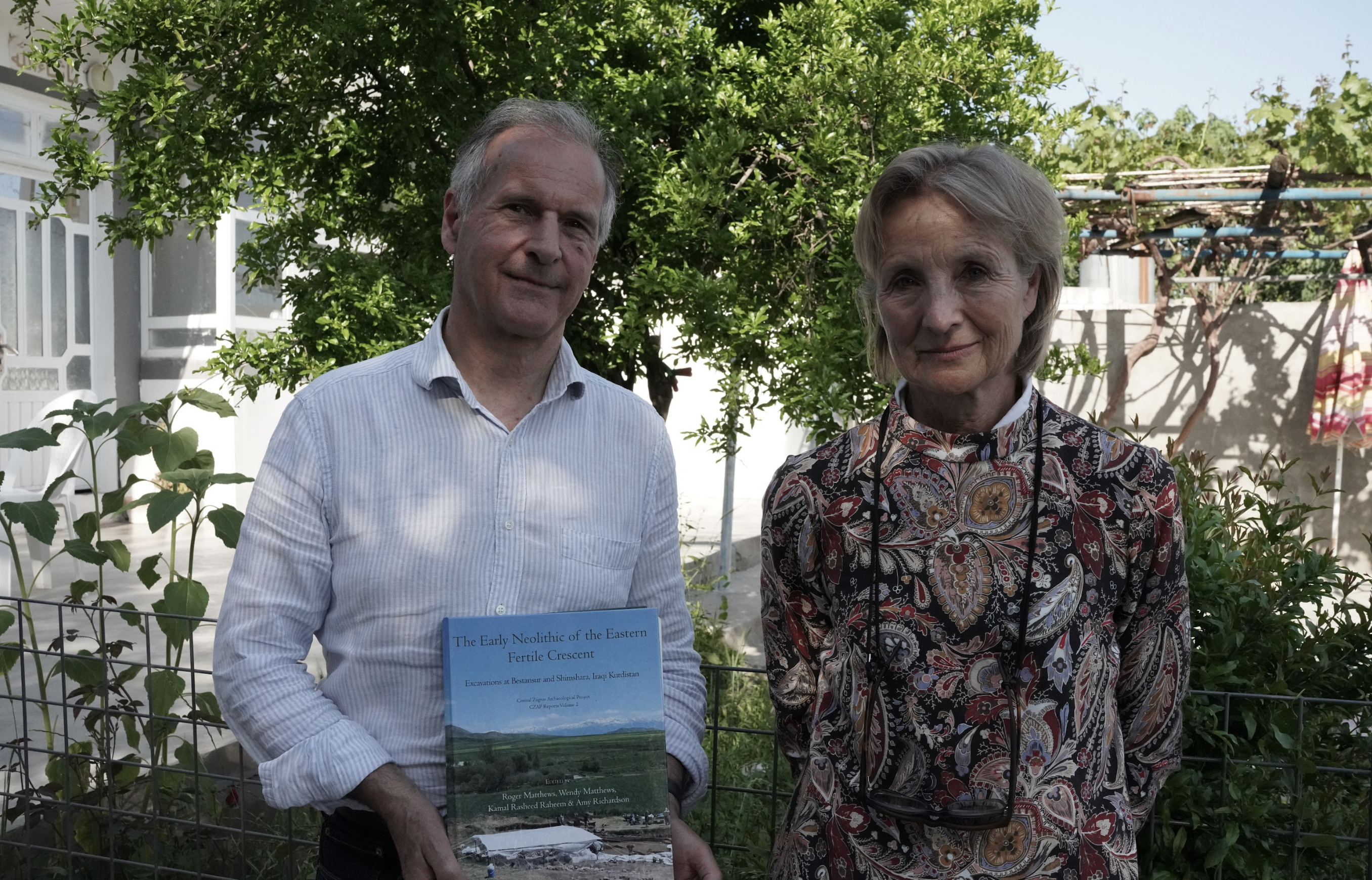

The site was first identified by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1950s and later surveyed by a German-Iraqi team in 2008-2009. Since 2011, Wendy Matthews, the co-director of the Central Zagros Archaeological Project, and Roger Matthews, Professor of Archaeology at the University of Reading in the UK, have spent many hours leading work and research on the site.

Speaking to Kurdistan Chronicle, Roger Matthews outlined the significance of the site. “We’re researching the transition from hunter and gatherer communities to more settled farming and agricultural communities with the herding of animals and growing of crops. This region, the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, is one of the first areas where that transition takes place. People make that change; they domesticate animals like goats, sheep, and cows, as well as crops like wheat and barley, mainly in the highlands zone to the east here. And then they settle and start to build sophisticated mud brick buildings,” he said.

According to UNESCO, Bestansur bears unique testimony to a cultural tradition and civilization from the distant past of humanity. No other archaeological site in the Kurdistan Region provides such early evidence for this critically important episode in the transition from mobile hunting-gathering to sedentary farming life.

Under the floors of Bestansur’s buildings rest many human burials, most notably in the middle building, where nearly 80 individual human corpses were found. “It’s a very special building where people brought their dead for final burial. This is during the so-called pre-pottery Neolithic period, so it’s before the invention of pottery,” Roger Matthews explained.

As research on the site continues, the team struggles to find a balance between protecting the site and analyzing it for research before further archaeological decay sets in. “Mud brick architecture has straw inside it to make it strong. But this straw, after 10,000 years, is not there anymore, so the mud brick is not very strong,” Wendy Matthews said. “Unfortunately, each season we must cover the buildings back up,” she added.

This problem is not unique to Bestansur. Across the world, very old mud brick buildings cannot be displayed because they are too weak. “At the moment, we’re making some noticeboards and panels to help visitors better understand Bestansur,” Wendy Matthews noted.

Surveying and analyzing

Published in 2020, The Early Neolithic of the Eastern Fertile Crescent: Excavations at Bestansur and Shimshara, Iraqi Kurdistan is a 720-page research volume on the excavations, surveys, and analyses undertaken by the Central Zagros Archaeological Project between autumn 2011 and summer 2017. Edited by Roger Matthews, Wendy Matthews, Kamal Rasheed Raheem, and Amy Richardson, it was published in the UK by Oxbow Books.

Wendy and Roger Matthews shared their sentiments about working on the Bestansur site. “Kurdistan is a very important region. We’re delighted to be working here. Bestansur has a long history of occupation because of the very important spring here, and there is biodiversity with the marshlands and the mountains.”

The archaeologists’ bond with the community has also made a huge difference to the project’s advancement. “We work very closely with the workmen in the village and the ladies; they help us with the sorting of the small finds. It’s very much a team effort,” Wendy Matthews underscored.

“It’s very important to stress that we feel very much part of the village family when we’re here,” Roger Matthews added.

Bestansur stands out for its unparalleled significance, as there are no comparable sites on the UNESCO World Heritage or Tentative Lists, either within Iraq or among its neighbors. Achieving UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List status would aid in protecting the site and its surrounding environment, including the second-largest spring on the fertile Shahrizor Plain and picturesque views of the Zagros Mountains. Bestansur reveals the roots of human civilization and is a testament to the legacy of our ancestors and their journey from survival to settlement.

Savan Abdulrahman is the editor-in-chief at DidiMn, a Kurdish cultural website. Concurrently, she is engaged in a research project on the origins of masculinity in her role as a research assistant at the American University in Iraq, Sulaymaniyah, and also collaborating on this project with the London School of Economics (LSE).