For the most part, the Kurds tend to garner the attention of the world only during major political events, such as the advent of ISIS in the Middle East. This attention, however, quickly fades. As a result, their artistic and literary work, along with other aspects of their history and culture, remain largely unknown to the global public.

When learning about the Kurds, borders and divisions feature prominently. Few indigenous groups have faced as many literal and figurative barriers as the Kurds, who have lived between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers for thousands of years. Since there is not enough room here to describe all the political, geographical, and historical barriers that have shaped the experiences of the Kurds, I will focus on some of them as they pertain to Kurdish poetry.

Classical literature

From the manuscripts that have survived to this day, we know that Kurdish literature emerged in the Middle Ages. The first lyrical texts come from Baba Tahir, who was born in 1010 and wrote his quatrains in the Luri dialect of Kurdish. The term Luri dialect points to one of the key difficulties regarding language within the Kurdish community: its spoken varieties can differ greatly from one another.

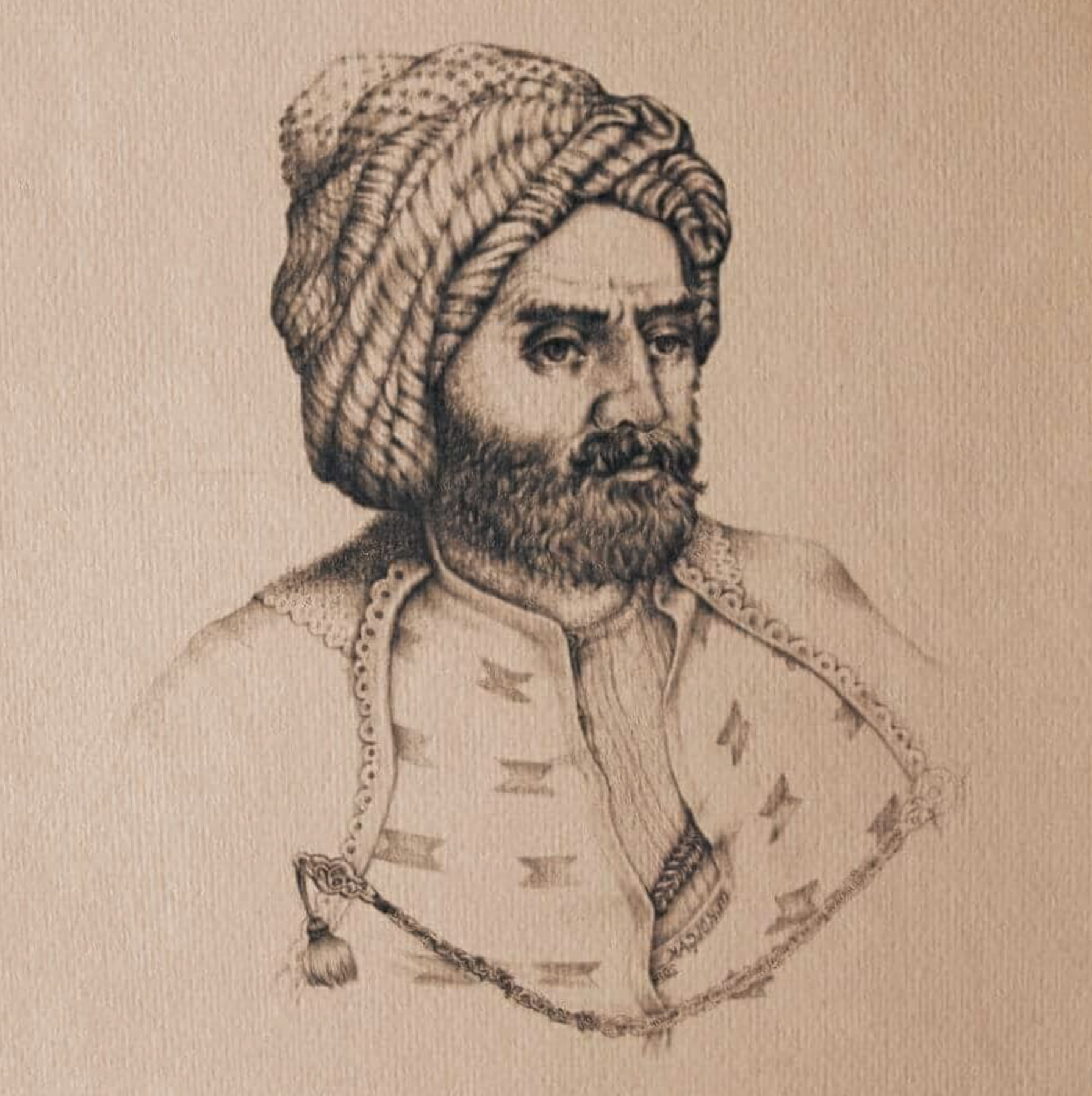

In addition to Luri, classical literature written in the Kurmanji dialect flourished under the rule of various Kurdish dynasties and emirates from the 16th century onward. Parallel to the literature of the neighboring Arab and Persian peoples, diwans (collections of poems) by writers such as Ali Hariri (1010-1079), Melaye Ciziri (1570-1640), and Feqiye Teyran (1561-1640) were promoted during these dynasties and have been generously received up to our time.

Among the classics, however, Ehmede Xani (1650-1707) stands out. His love epic Mem and Zin, written before the French Revolution, alludes to aspects of identify and implores the Kurds to elevate their language as a tool for bolstering their power over their territories. In a 1694 mathnawi (a poem written in rhyming couplets), he evokes national ideas, for instance by starting the action of the poem on Newroz, the Kurdish New Year.

In the Sorani dialect, written literature developed from the 18th century onwards. Literature in Zazaki emerged only at the end of the 20th century.

As the Kurdish dynasties declined in the 19th century, so do did Kurdish language and literature. After World War I, these dynasties disappeared completely from the map, replaced by the creation of four European-enabled nation states in the region. The basis for Kurdish self-preservation also disappeared, and the societal divisions that were forged remain in place today.

Political framework

Since then, Kurdish language and literature have taken different paths in different countries. In the former Soviet Union, which had a small number of Kurdish speakers, the Kurdish language was promoted during Lenin’s time and after Stalin’s death. There, it was present in schools and media until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, due to the politics of the Cold War, there was little exchange between those engaging with the language in the Soviet Union and Kurds in other states.

Following the 1923 founding of Turkiye, where most Kurds live, the Kurdish language suffered major repression. Kurdish was legally banned by the state until 1991, when the law was repealed. Despite this positive step, Turkiye is still a long way from a complete normalization. Kurdish remains absent from public life, apart from a two-hour elective course in middle school and a few Kurdish departments at select universities. While there has been some progress in private media, there is a complete lack of support and funding by the state. Written Kurdish is usually learned autodidactically.

In Syria, Kurdish was tolerated in the press during the French mandate but was banned in the 1950s. With the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, however, Kurdish became the official language in the Kurdish-majority areas.

In Iraq, Kurds faced persecution and genocide from the 1920s to 1991. However, the language was not always banned; Kurdish radio broadcasts and publications were allowed, and Kurdish was taught as a language in schools, despite being disallowed during various periods. Since 1991, Kurdish has been the official language in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

There has never been an explicit ban on Kurdish in Iran; like in Iraq, Kurdish media and publications were permitted but the language was also absent from public life.

In addition to this politically complex and repressive approach to the Kurdish language, there is another set of barriers for Kurdish: it is written in the respective country’s alphabet that is then modified for Kurdish. This means that Kurds use the Cyrillic, Arabic, or Latin alphabets depending on which country they are from.

Modern poetry

Poetry was the primary genre among the Kurds until the middle of the 20th century, but modern Kurdish poetry has its roots in the work of the 19th century poet Haci Qadir Koyi (1817-1897). Koyi’s poetry remains true to classic poetical forms like the ghazal or qasida, but in terms of content it expresses aspects and themes of modern national life, such as the right of self-determination of peoples, as well as technical developments.

Koyi brings a romanticizing, heroic imagery to Kurdish poetry, which represents a turning point from poetry’s focus on religious and ascetic themes and ideas. This change accelerated at the start of the 20th century for two reasons. First, from 1898 onwards, Kurds began to publish magazines and newspapers in which these texts were disseminated. Second, the number of people attending state schools increased, helping to form a more worldly, secular class than that formed by the classical religious schools (madrasas).

Koyi’s poems were published posthumously in the newspaper Jin (Life) in Istanbul in 1918. In the same magazine, the poet Abdurrahim Rahmi Zapsu (1890-1958) introduced a new style by integrating elements of spoken language, which was free from formal rules, into Kurdish poetry. Zapsu abandoned the structure and subject matter of classical poetry and used rhythm and symbolism as the basic elements of his poems, which focused on political and social themes.

Other themes and forms also found their way into Kurdish poetry. Modern forms began to be published, including lyrical poetry, sonnets, ballads, haikus, free verse, and even newer experimental varieties, alongside the ghazal or qasida. The classical forms did not disappear; instead, they continued to exist alongside modern varieties of poetry until the middle of the 20th century.

Although modern Kurdish poetry publications do not show linear development – they either continued to publish where they had been established or changed their place of publication (for example, from Cairo to Geneva) – Kurdish poetry has constantly reinvented itself and interacted with world poetry.

Up to the end of the 20th century, Kurdish poetry primarily dealt with socio-political themes such as the division of Kurdistan, linguistic repression, force and reprisal, imprisonment and detainment, questions of identity, nature, and migration.

The imagery used to describe these themes, however, is strongly influenced by the natural surroundings of Kurdistan. Words such as gul (rose), berf (snow), and ciya (mountain), which are synonymous with the land, are used along with elements from folklore and mythology. Over time, mythological images and metaphors from other cultures have also increasingly made appearances in Kurdish poetry.

More recently, new forces and themes have shaped Kurdish poetry, including urbanization, the anonymity of city life, individuality, philosophical-existential questions, feminist approaches, and migration, as well as the quotidian joys and challenges of the poets conveying their individual and collective experiences.

Abdullah Incekan is a Kurdish writer and expert in German and Turkish language, literature, and culture.