Kurdish poets have long likened their lovers’ bosom to the pomegranate fruit. For example, in his classic love poem, Mem û Zîn, Ahmed Khani (1650-1707) likened the pomegranate fruit he saw in the garden of the Kurdish prince, Zain al-Din, in Botan to a girl’s bosom. Of course, there is a wealth of poetry in the same vein written by other poets across Kurdistan, as well as close similes in Kurdish folk songs. The cheeks are even called hinarên rû (literal meaning “pomegranate face”) in Northern Kurdistan (southeastern Turkey), a symbol of radiance and vitality.

In addition to the pomegranate being referenced in poems and folk songs, it has, as an autumn fruit, enjoyed an important place in Kurdish society. What is the story of the pomegranate and why celebrate such a fruit? Let us start with Halabja, which was subject to the full brutality of the former Ba’athist dictatorial regime, and has now become a symbol of love, benevolence, fertility, and growth.

On November 2, 2022, the Ninth Halabja Pomegranate Festival was launched, which attracted the participation of 600 farmers, with 720 stalls and booths provided for farmers, orchard owners, and merchants to display the products of their farms and trees.

During the closing press conference of the festival, Director General of Tourism in Halabja Governorate Chia Qasim, announced that 270,000 tourists had visited the governorate to attend the ninth edition of the festival. Over the course of three days, Qasim indicated that crops worth 1.35 billion Iraqi dinars ($850,000) had been sold.

Statistics from the first day of the festival also showed that 35,200 tourists visited Halabja Governorate through the Zameqi and Darshish border gates with Iran and another 35,000 visited from Halabja center, amounting to 70,200 people in total. As for the statistics from the second day, the same two checkpoints recorded 85,000 tourists crossing into Halabja Governorate, compared to the total number of visitors, which was 120,000.

This may not be a surprise to those in the region, as the pomegranate in Kurdistan exhibits some characteristics that make it better than the other types grown elsewhere. It is rather large, has large seeds, and its surrounding arils are full of juice. The taste varies between sweet, sour, and umami. Pomegranate molasses, which is made from a high concentration of the finest juice, gives salads an unmatched taste. I remember buying a bottle of pomegranate molasses from the border town of Tawila in 2015 at what I thought was a high price, but when I used it, I found that it was well worth it thanks to its high quality and wonderful taste.

The story of the pomegranate

Cultures in Mesopotamia have grown the pomegranate since antiquity. The book Dirasat u Buhuth (Studies and Research), which includes articles written by the Iraqi archaeologist Taha Baqir (1912-1984), states that ancient cuneiform tablets discuss the pomegranate, known as narmu in Sumerian.

We can note here that the Sumerian name is close to the fruit’s Kurdish names that are used today: hanar, anar, and nar. Likewise, the Sumerian word is linked to the Arabic word for pomegranate, rumaan, where the letters are almost the same but rendered in a different order.

Pomegranate is a Kurdistani fruit par excellence. Its cultivation areas are scattered throughout the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), especially in Halabja, Horaman, and Sharazur . The Kurds take a keen interest in this fruit, growing it in their homes and farms. Many make a refreshing beverage from it or add its dried seeds to some dishes; others manufacture pomegranate molasses, which can be used in cooking and salads. Pomegranate peel powder is also used in tanning hides (mashik in Kurdish) and leather.

This fruit is sacred in both Yarsanism and Islam. When I was a child, I used to make sure not to waste a single seed when I ate pomegranate. As our elders would tell us, “there is no pomegranate on earth without a pomegranate seed from paradise in it,” basing their claim on a hadith ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad.

The word “pomegranate” is mentioned three times in the holy Qur’an. In the Ar-Rahman Surah, there is a description of Paradise: “Therein will be fruits and dates and pomegranates.” This is where the idea – that in every pomegranate lies a single pomegranate seed of paradise - originated.

In Yarsanism, there is a story about the virgin Dada Sara, daughter of Pir Michael. One day she was cleaning the religious meeting place, or cemxane. People at the gathering had eaten pomegranates, so she had found an errant seed on the ground. She picked it up and ate it because she believed it was sacred and should not be left on the ground. After a while, Sara became pregnant and gave birth to a child, whom she named Bawa Yadgar. Still the people doubted her virginity, so Sultan Sahak asked them to throw the child into a tandir oven and leave him for three days to test Sara’s purity. After three days had passed, they opened the oven and saw the child was still alive and not burned.

In ancient paintings and sculptures from West Asia, the cradle of the pomegranate, we find portraits of kings and clergymen holding either pomegranate flowers, its fruits, or even branches ending in small pomegranate fruits. Some believe that the crowns of kings are nothing but an imitation of a pomegranate, with multiple triangles pointing upward.

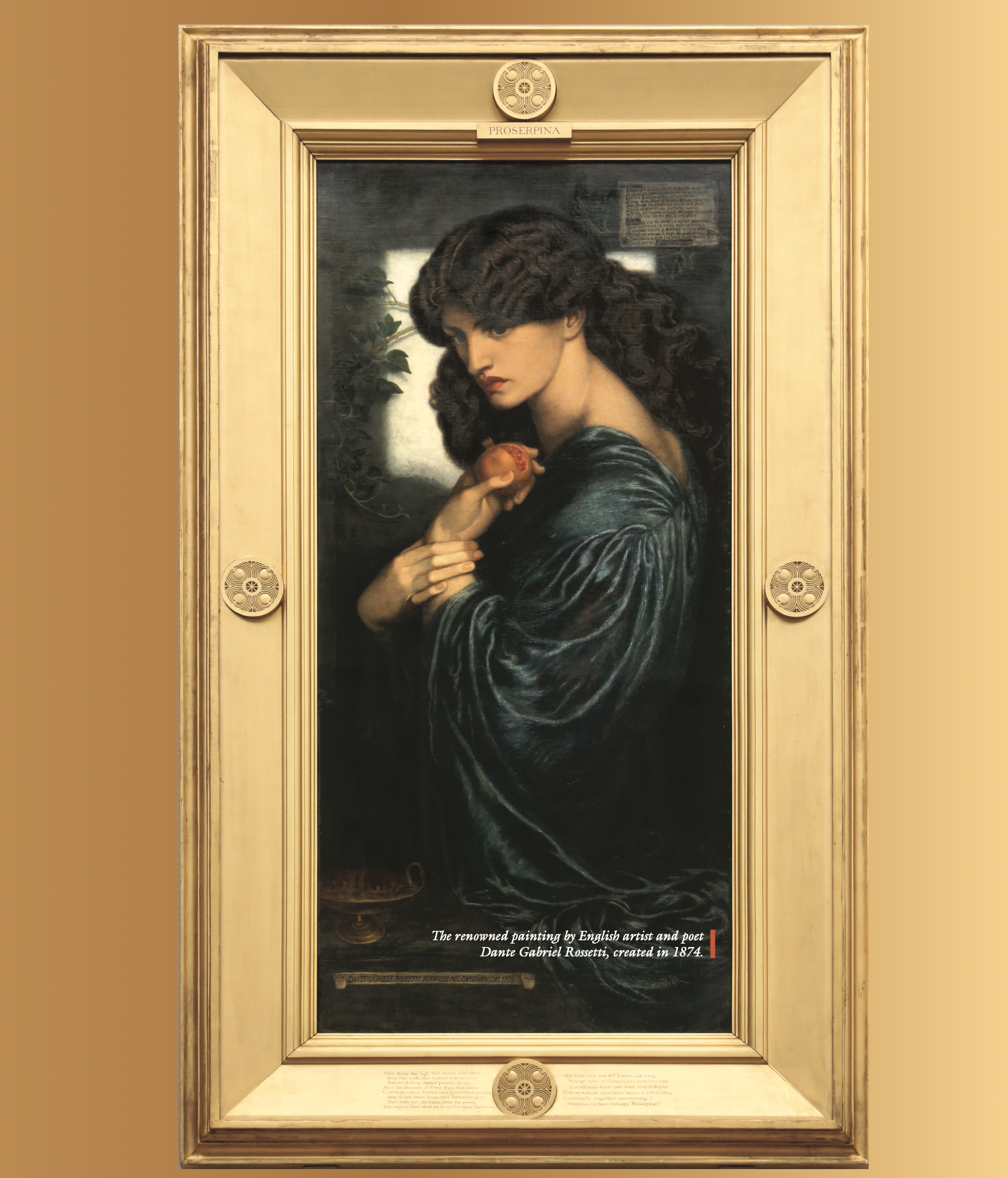

The Greeks knew about the pomegranate in the eighth century BC, as it was mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey. In his book Das Granatapfel Buch, Bernd Brunner states the fruit was closely linked to the goddess Aphrodite in Greek mythology. Legend has it that Paris gave Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and love, a pomegranate as a sign that she was the winner in the beauty contest between her, Hera, and Athena. It is said that Aphrodite subsequently planted a pomegranate tree in Cyprus. There are other Greek myths linked to pomegranates, such as the myth of Persephone, daughter of Zeus and Demeter, but there is not enough space here to tell it.

Studies show that the pomegranate tree arrived in Spain with the Arabs in the eighth century AD. Granada, therefore, was named in reference to the pomegranate trees that were planted there. In the Middle Ages, the pomegranate was considered by Christians to be a symbol of virginity and purity. In Boticelli’s 1497 painting, The Madonna of the Pomegranate, the baby Jesus sits on her lap, holding a ripe pomegranate.

A symbol of Kurdistan

One year ago, pomegranates were the subject of a phone call between Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Prime Minister Masrour Barzani and UAE President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, where they discussed ways to strengthen bilateral relations, especially with regard to trade and investment.

Prime Minister Barzani also thanked President Al Nahyan for the strong support, cooperation, and coordination shown by Emirati officials in supporting the export of agricultural products, especially pomegranates, to the UAE and other Gulf countries. Mr. Barzani confirmed in the same phone call that the KRI can play an important role in providing food security in cooperation with the countries of the region. He also indicated that the export of pomegranates represents an stepping stone to the export of other agricultural products, including apple, grapes, and honey.

Yes, the Kurdistani pomegranate can play a pivotal role in strengthening relations between the peoples of the region and may become, like olives, a symbol of peace and love. This fruit has become a product that represents Kurdistan in global markets and will be present on the tables of restaurants and home kitchens around the world. Tons of this product have already been exported to the UK and France, and the volume of pomegranate exports from the KRI has reached 100 tons, with a target of 1,000 tons by the end of the year, as stated on the KRG official account on the X platform, formerly known as Twitter.

This is all thanks to the KRG government, which has adopted projects related to this fruit, providing support for farmers’ projects as well as encouraging investors to open factories to manufacture pomegranate molasses and export it to global markets.

Jan Dost is a prolific Kurdish poet, writer and translator. He has published several novels and translated a number of literary Kurdish masterpieces into Arabic.