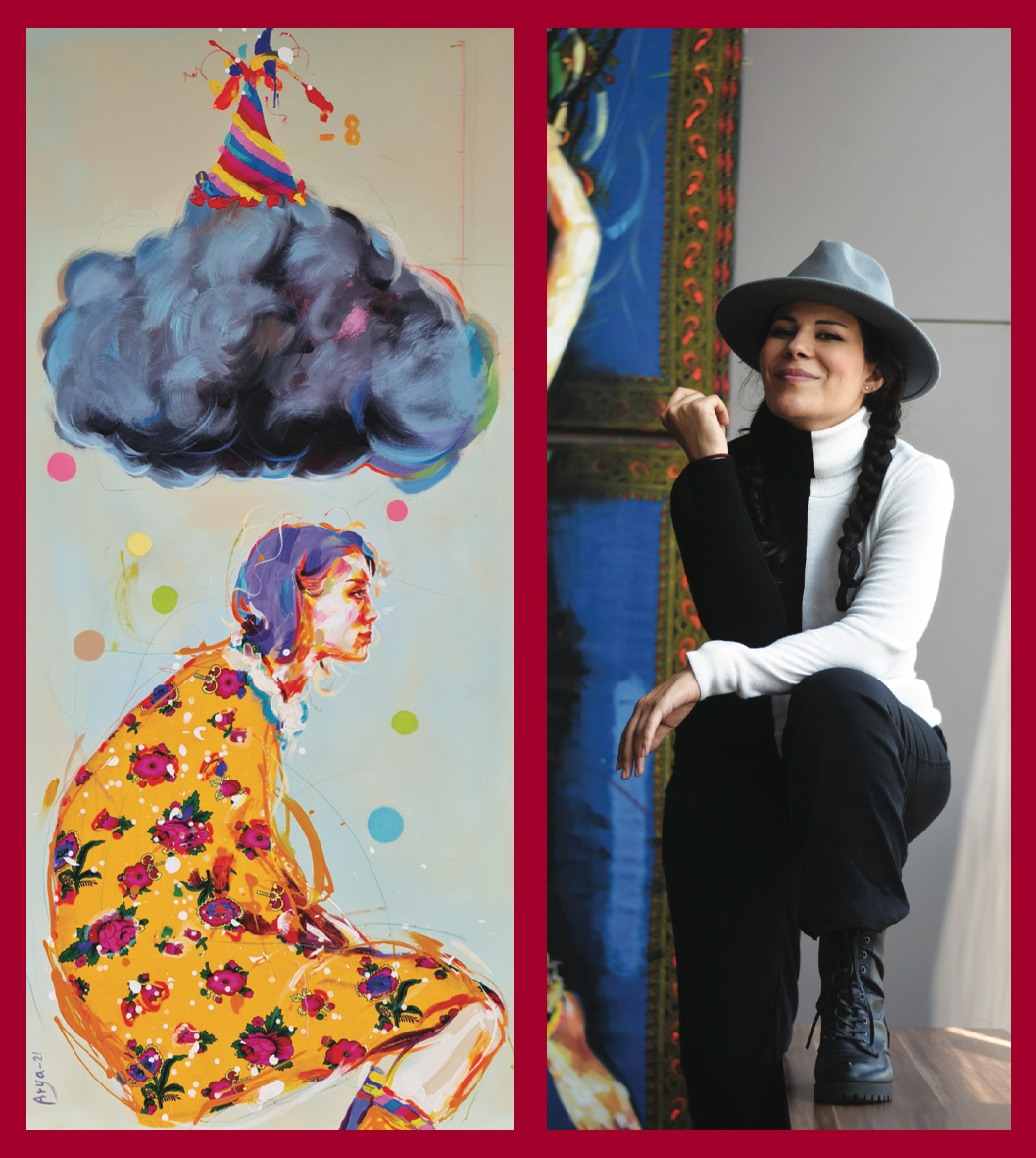

In this interview, Arya Atti, a Kurdish gallerist and painter from Kobani, Syrian Kurdistan, shares her remarkable journey as an artist seeking refuge in Germany amidst the turmoil of war in her homeland. Having participated in 40 exhibitions across Europe and the Middle East, Arya discusses how art played a pivotal role in her integration process in a new country. She delves into the challenges of finding her artistic identity and the profound influence of renowned artists like Frida Kahlo on her work. Through her paintings, which incorporate unique Kurdish fabrics, Arya showcases her deep cultural connection and endeavors to foster unity and understanding through art. The interview also explores the essence of Kurdish art, a medium reflecting just causes and political messages, embodying the resilience and diversity of Kurdish identity through the ages.

Kurdistan Chronicle (KC): What caught my attention in one of your conversations is when you said, "I arrived in Europe barefoot.” Let's start from this point. What was your motivation to migrate from your country? We understand the conditions of war, but the reasons for an artist's migration differ from those for an ordinary person. Do you regret migrating?

Arya Atti (AA): My primary motivation was the search for safety, as we were cut off from the means of living in Syria due to the conditions of war. Art didn’t play any role in my decision to migrate, and I don’t regret the decision. Instead, I feel that it was my destiny and that I was born in the wrong place, where nothing in my country resembles me, and my society could not accept me as a female artist.

KC: In Germany, your country of asylum, how were you able to integrate so quickly? Did art help you in that process, or did German state institutions play a bigger role? If you weren't a creative artist, would you have integrated into German society as quickly?

AA: I have several paintings where I depict myself, and on my features, you can see the cultural shock that I experienced here in Germany, despite being an open-minded person towards others with a heart capable of loving people with their differences. I found that the differences are significant, not only in terms of language, food, and other customs, but even in the way people express their emotions and connect with others. All these curious blue eyes around me astonished me. They would gaze into my eyes with intense focus during every conversation. Sometimes, I felt they loved me, and other times, I felt they didn't know me at all. It was very perplexing because, based on my psychological makeup, I strongly needed others in order to see myself.

Here in Germany, I couldn't find the classical realistic art that I had learned at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Aleppo. There was a moment when I realized that everything I had learned and drawn before had no place in this country. I didn't seek integration as a person so much as I strove to achieve artistic integration or find a common language with my new surroundings. That's why I am currently working on a project to help refugee artists find their own identity here and provide them with a platform to meet art collectors and those interested in drawing. I offer them the necessary legal guidance and information and introduce them to the press to generate publicity. Several German state entities do provide support to art and artists to a certain degree, but one has to drown in a sea of paperwork and bureaucracy to register future art projects, which is quite challenging.

I continue drawing relentlessly and have an audience that plays the most significant role in my integration and success. I like to refer to this artistic audience as my army. They are my strength and greatest support. Since my first year here until now, I have found many people around me who are very much like angels. They provide me with the necessary emotional security to grow and prosper.

KC: Do you experience anxiety in your creative projects? Put another way, are you still searching for Arya Atti the artist in your paintings? I noticed that many of your exhibited artworks feature portraits that embody you. Can we say that your ego is at its highest level?

AA: The process of creating a painting is a search for self-discovery. I have existential anxiety, and drawing gives me certainty and sometimes directs me towards a place from which I can embark on broader worlds. Through my artwork, I express and convey the emotions that I experience as a human being, influenced by my life experiences of being a refuge and experiencing war, racism, marriage, motherhood, and divorce. These paintings document and represent the state of many women like me who have gone through similar experiences. In Europe, my paintings have received significant responses from European women.

I always try to break out of my emotional and psychological circle to engage in side projects such as collecting Kurdish myths or documenting children's group games in villages, but I always return to my own worlds, as if I was alone on this earth. As for the ego, I can say that I have a troubled personality and lack the ability to appreciate myself. I only feel my existence when others love me, when I draw, or when I see smiles from those who view my paintings. I have become addicted to these moments, the moments of the viewer's encounter with my artwork. I don't wait for people's comments or praises, but the astonishment of the viewers creates a special pleasure within me.

The search for identity does not mean being selfish and revolving solely around ourselves. The "self" is a stage in the process of creation, and I am still searching for my own identity. Every artwork is a field for exploration. There are paintings in which I have not discovered anything technically or personally. These paintings do not mean anything to me and will likely never see the light of day. Meanwhile, there are paintings that I hold dear to my heart, pricing them exorbitantly so that they won't sell quickly and will remain close to me for as long as possible.

KC: How deeply were you influenced by international artist Frida Kahlo? How do you evaluate her unique school of art?

AA: We didn't have good educational staff or models at the Faculty of Arts at the University of Aleppo, and simply by drawing every day for four years, one learns the craft. I didn't have sufficient artistic knowledge or internet access, and artistic questions multiplied in my mind for which I couldn’t find suitable answers.

One time, I found a book about the paintings of Gustav Klimt, Vincent van Gogh, and Frida Kahlo in the college library. I considered it a great event, like a tremendous explosion happening in my imagination. I found the answers that I had long sought through contemplating the paintings of those great masters. I started to paint their works in my imagination and was greatly influenced by them. I can say that the colors of my paintings carry the impression and color wheel analysis of Van Gogh, while in the compositions of my paintings, you can find Gustav Klimt's figures. In presenting my subjects, we can talk about the influence of Frida Kahlo, who lived through similar circumstances as I. These are the teachers who have influenced my art, and I engage in long imaginary dialogues with them.

KC: Where is the man in your paintings? Why do you exclude him from your artistic worlds? Are you seeking revenge against men in your artwork?

AA: I have two experiments where I depicted a man without features in one, and in the other, I covered the entire form of the man with silver color. I can say that I have started to doubt my abilities in drawing because I don't know how to draw a man as I should. Yes, there is anger within me towards men. I have witnessed nothing but disappointment from them, but I am making a conscious effort with myself to resolve this crisis!

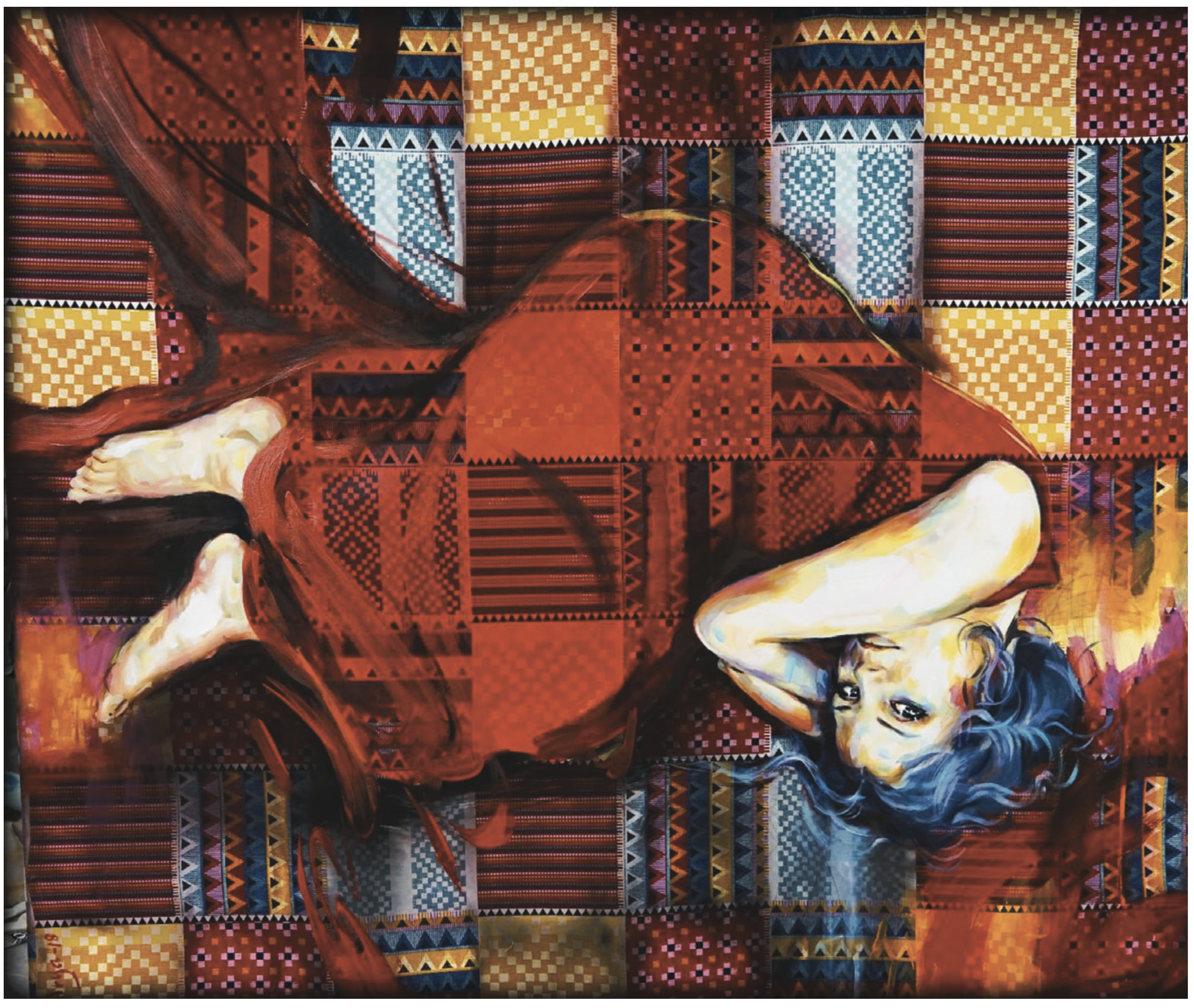

KC: Where did the idea of using Kurdish fabric in your paintings come from? What is the impression of the German audience when they see these paintings that blend high artistic skill with the unique Kurdish colors?

AA: I was in a refugee camp and didn't have enough tools and colors for painting, so I used bed sheets, curtains, and all available fabrics to paint on and use them as collages to provide color. Kurdish patterned fabrics have always fascinated me, so I decided to incorporate them into my paintings and develop this technique with a contemporary artistic style that approaches pop art and abstraction. We Kurds have a colorful and rich identity, which enriches my experience and gives it a unique identity. The war has separated us from our country and from each other, but our culture, music, food, and stories bring us together once again. We want to positively share this diversity with other cultures. Differences can be positive, and we can utilize them to build bridges and exchange ideas, rather than for making war and bloodshed. Culture and art are our tools against war.

KC: You participated in a global exhibition in Poland with Kurdish artists. How familiar are you with the progress of Kurdish art in Kurdistan?

AA: Yes, I had the privilege of meeting a large group of Kurdish artists, who were prominent figures in Kurdish art, at the Bydgoszcz City Museum in Poland, which received great interest from Europeans. It is evident that Kurdish art carries within it a just cause, revolution, message, anger, and sorrow. Sometimes I feel that Kurdish art is somewhat harsh for Europeans. If we compare Kurdish art to European art, we find that Europeans tend to use art as a means to alleviate the harshness of life. For example, you may find an artist hosting an exhibition about their relationship with their bicycle, abstract ideas, or even an interactive art exhibition.

Kurdish visual art is a serious and vibrant art form that has been passed down from generation to generation for thousands of years. It evolves naturally due to the ever rebellious and restless nature of the Kurdish people, as well as the migration of Kurdish artists to many countries around the world. Through influence and inspiration, we have a tremendous diversity in artistic identities, but the existential issue and political message always weigh heavily on these identities. Thus, they are framed, confined, and packaged. In my opinion, art should be liberated from these burdens, allowing the artist's imagination to create unique human aesthetic concepts.