This intriguing article takes readers on a captivating journey through the streets of Diyarbakir, a Kurdish city in Eastern Turkey also known as Amed. Delving into the intricate interplay of history, culture, politics, and identity, the author paints a vivid picture of this remarkable place. The city's old town, enveloped by ancient Roman fortress walls, exudes an air of enchanting beauty and enigma. However, as the author ventures into the newer parts of Diyarbakir, they bear witness to a profound transformation characterized by the emergence of numerical street names and an ever-widening divide between the privileged and marginalized areas.

As the author continues his exploration, a quest marked by ambiguity, he strives to illuminate the harsh realities faced by the Kurds in modern Turkey. He notes with dismay that the streets of present-day Diyarbakir bear the names of politicians and writers who hold no connection to the city, while the names of celebrated Kurdish individuals from Diyarbakir remain absent. In a symbolic gesture, the author imagines naming a street after Mehdi Zana, a Kurdish author, politician, prominent Kurdish political activist and former mayor of Diyarbakır expressing his hope that this act of imagination will one day become a reality.

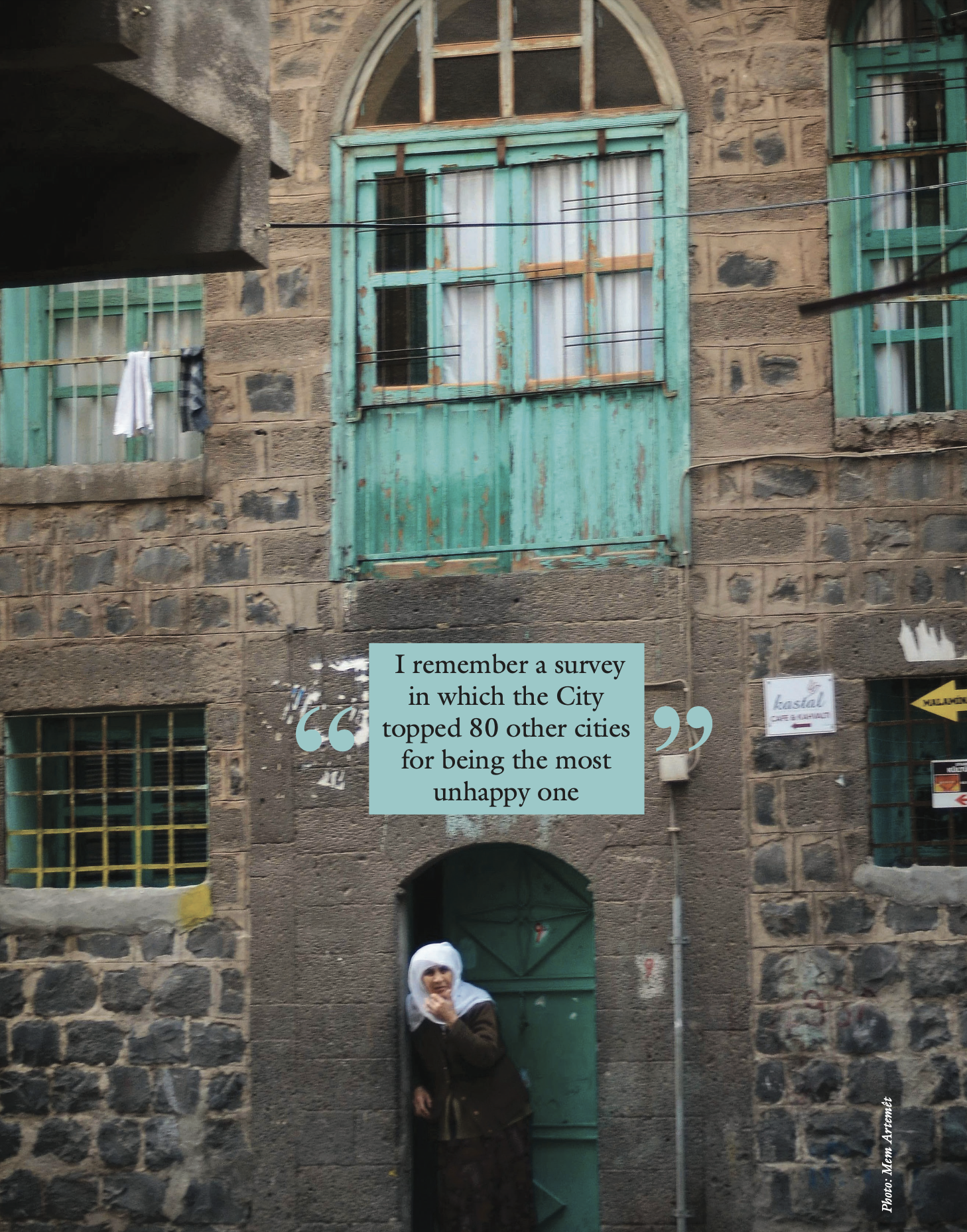

The old town is crammed between the huge, black-stoned walls of a wide ancient fortress. Finding it on the map, one encounters a miscellany of names flowering the short lines of its narrow alleys, which seem to punctuate the flat belly of a turbot fish.

Moving out from the high walls of the fortress towards the sprawling settlements that constitute its new heartland and render the old town a more marginal place, one perhaps only for curious tourists, one begins to see a gradual numeric table dotting the streets. While numbers swarm in the short lanes of blocks, replacing the words of the old town’s experimental poetry, some blocks look blank in the less wrinkled face of the City, as if they are still unsure if they are ready to exist.

Going further, full names of people denominate the long lines that are the streets and recently built popular boulevards. Ranging from presidents and prime ministers of the Turkish Republic to famous Turkish poets and writers and, surprisingly, a few well-known Kurdish figures like Musa Anter, a list of names leaves encyclopedic footnotes along the long lines of the City’s main arteries. Some names make no impression on me. I don’t know who they are. I know the places, however. I have been to many streets. And I know more than the map shows, no matter how much I zoom it in. Yet, it is all kind of strange. I feel strange.

Getting further away from the old town, one gets closer to higher buildings, more spacious apartments, more luxurious entertainment spaces, and better designed parks and streets. Diary shops, kebab and lahmacun restaurants, dessert shops, doner shops, nuts-and-seeds shops, and cafes appear in an infinite line of recurrence along the pretty straight lines of the boulevards. I get the weird Napoleonic impression that all the armies move on their bellies. The pandemic and the recent devastating earthquake might have made people’s struggle for finding food more visible to me. I don’t know. Yet, I can’t help but develop a sense of frustration. I remember a survey in which the City topped 80 other cities for being the most unhappy one. Another statistic showed that it also lagged far behind others on the cultural development index. And I usually come across someone who nonchalantly spits on the ground. I try to forget. I try not to see. I live the city. I leave the city.

Pacing a once quite busy street named after an old mayor of the city, Dr. Ahmet Bilgin, I realize that currently the only elected officials left in the City are mukhtars, i.e. neighborhood representatives who barely hold any authority but are usually the most fierce and furious ones during election campaigns and have the most uncompromising stances against accepting election results if their side loses.

I gather democracy is not the art of winning, but the art of losing. And it is always undermined by those who can’t bear a loss. Citing 1950s Turkey, which held the first free and fair elections and during which a peaceful transition of power was implemented for the first time in the history of the Middle East, famous historian Bernard Lewis remarked that “the electoral defeat of C.H.P. was its greatest achievement.”

One of the biggest worries among those who opposed the current government in Turkey before last elections was whether the ruling party would peacefully leave power. That assumption depended on the fact that the opposition would win the elections, but since this didn’t occur, we will never know if their worries were well placed. The current post-election mess in politics makes it clearer that many things outlast governments and power changes. And the promised heaven is postponed until the next call, not because some can’t win enough but because some can’t lose enough.

There is always something bizarre lingering behind the dark blue bubbles of demagogy and propaganda. They never let one grasp the full truth. That’s what I feel when I turn right from a crossroads on the widest boulevard of the City, which is named Mahabad, to the Nazım Hikmet Boulevard.

Hikmet was a famous Turkish poet born in Salonica with a Polish-Turkish lineage. He was jailed for a dozen of years after being charged for making communist propaganda and then passed away in Moscow in exile in 1963. Paying tribute to his memory, the recently opened street was named after him by the former city council, which was governed by the pro-Kurdish Party. A Kurdish poet living at the same time as Hikmet in Turkey would undoubtedly have been jailed simply for claiming that he is a Kurd or trying to speak and write in his native language, a charge that not a single Turkish author would ever be tried for. And his or her name would never ever be shining on the big blue signboards labelling the streets of a Turkish city.

Suddenly, I want to get in a taxi and tell the driver: “Take me to the Mehdi Zana Street.”

A brilliant charismatic young man working for a tailor, Zana had run for mayor in 1977. It was the first time in the City’s history that one representing Kurds dared to run for the office. He drew huge support from people and, conversely, severe backlash from Turkish authorities. He was detained and tortured but didn’t relent. He rejected to testify in the courts in any language other than Kurdish, and, winning the election, managed to sit in the mayor’s seat with the pains and stains of the heavy tortures that had been inflicted on him and been meant to deter him from running and gaining the post.

I dream about a wide, bustling, luminous street with lots of cultural spaces under the canopy of a large oak with plane trees on both sides. And perhaps a proud and glorious statue of his resistant soul at an intersection, beaming his sincere Kurdish smile from there. I am sure Nazım Hikmet, whose poetry I admire, would also be more than willing to see his name replaced by Zana’s on the street. Yet, I can’t bring myself to ask any driver to take me there. There is no Mehdi Zana Street in the City. And no language to complain about its non-existence. Maybe one day there will be. And maps could look fairer and sweeter.

Ciwanmerd Kulek is a writer and translator based in Diyarbakir. He has a degree in English Language Teaching. He is the author of several novels and short story books in Kurdish, and has translated a dozen of works from the world literature into Kurdish.