The existence of an ancient Kurdish alphabet was known only to a small group of Kurdish intellectuals but had no tangible evidence supporting it. As a child, I heard this idea more than once during my father’s meetings with his intellectual friends.

Discovering the source of the Kurdish alphabet

As an adult, my hopes of finding the alphabet have long been disappointed. My first discouragement came as a preparatory student in Damascus, when ‘the Kurds’ were mentioned in my history textbook—perhaps the only time the term evaded Syria’s textbook censors—and one of the students asked the teacher: who are the Kurds? He responded to the extent that he could, but another student asked: do they have special letters? He answered in the negative, prompting me to state proudly that the Kurds had indeed had special letters since ancient times but had abandoned them. This prompted the old teacher to mock me, saying this was just a fabrication until proven otherwise. When I returned home, I searched throughout my father's huge library but only found a single orphan line in Kurdistan and the Kurds by Mulla A el-Kurdi that was not supported by a reference. I realized then that I had no reliable evidence to prove the claims I believed to be true.

Later, while studying for my master’s degree in 1999, I found mention in both the Dictionary of Arabic Publications by Elian Sarkis and a biography of Ibn Wahshiyya, which noted Wahshiyya translated books from Kurdish! I then learned that Wahshiyya’s Shawq Al-Mustaham had been printed in Europe two centuries before and that the original manuscript was more than ten centuries old. So I set out in search of the book, hoping to find titles of other old Kurdish books in the process. Little did I know that this search would lead me to discover the Kurdish alphabet!

In 2003, I was working as the director of the Digital Manuscripts Center in Damascus, when I wrote to several parties to obtain a copy of the manuscript. I learned that Ayad al-Tabbaa had discovered a new copy in Iran, which had been issued in print. What surprised me was that he described the Kurdish alphabet in detail and how its letters corresponded to those in Arabic. Consequently, I obtained the reviewed edition of the book by the Austrian Orientalist Joseph von Hammer.

After this, I published a series of articles about these discoveries in the electronic newspaper Al-Kurdiya News in the UAE, translated by Dr. Haşim Özdaş into Turkish for the 5th issue of the Kurdish history journal Kürt Tarihi in Istanbul in 2013. Özdaş also translated them into Kurdish for the 4th issue of the Journal of Living Languages Institute at Bingöl University in 2016. Most recently, our friend Dr. Khanzadi Sabah gave a lecture about the discoveries to her students in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Ibn Wahshiyya and his book

Ahmed bin Ali, known as Ibn Wahshiyya, was Chaldean by origin and a chemist and scholar of other sciences. He authored books and translations, including from ancient Kurdish.(1) Al-Fihrist by Ibn el-Nadim in the 11th century is the oldest Arabic bibliography that is known to exists. In it, Ibn Wahshiyya is described as one of the translators of Nabataean into Arabic, and the titles of many of his works are provided.(2)

The importance of the book, which he wrote in the year 241 AH/ 856 AD, lies in the fact that it deals with dozens of ancient languages and deciphers their letters in Arabic, including hieroglyphs. Noted French Orientalist Jean-François Champollion is one believed to have benefited significantly from Wahshiyya’s work.(4)

The first to discover the manuscript was Hammer, who printed it in London in 1806. Nearly two centuries later, it was printed by Ayad Al-Tabbaa in Damascus in 2003, after a new copy was discovered in Iran in 1998. As for the available copies of the manuscript, there are, as far as I know, three: British Museum copy No. 444. H.173, a copy in the Sepahsalar High School Library in Iran No. 3312/2863, and a copy dating to the Ottoman period preserved in the National Library of France, No. Arabe 6805.

Was there more than one Kurdish alphabet?

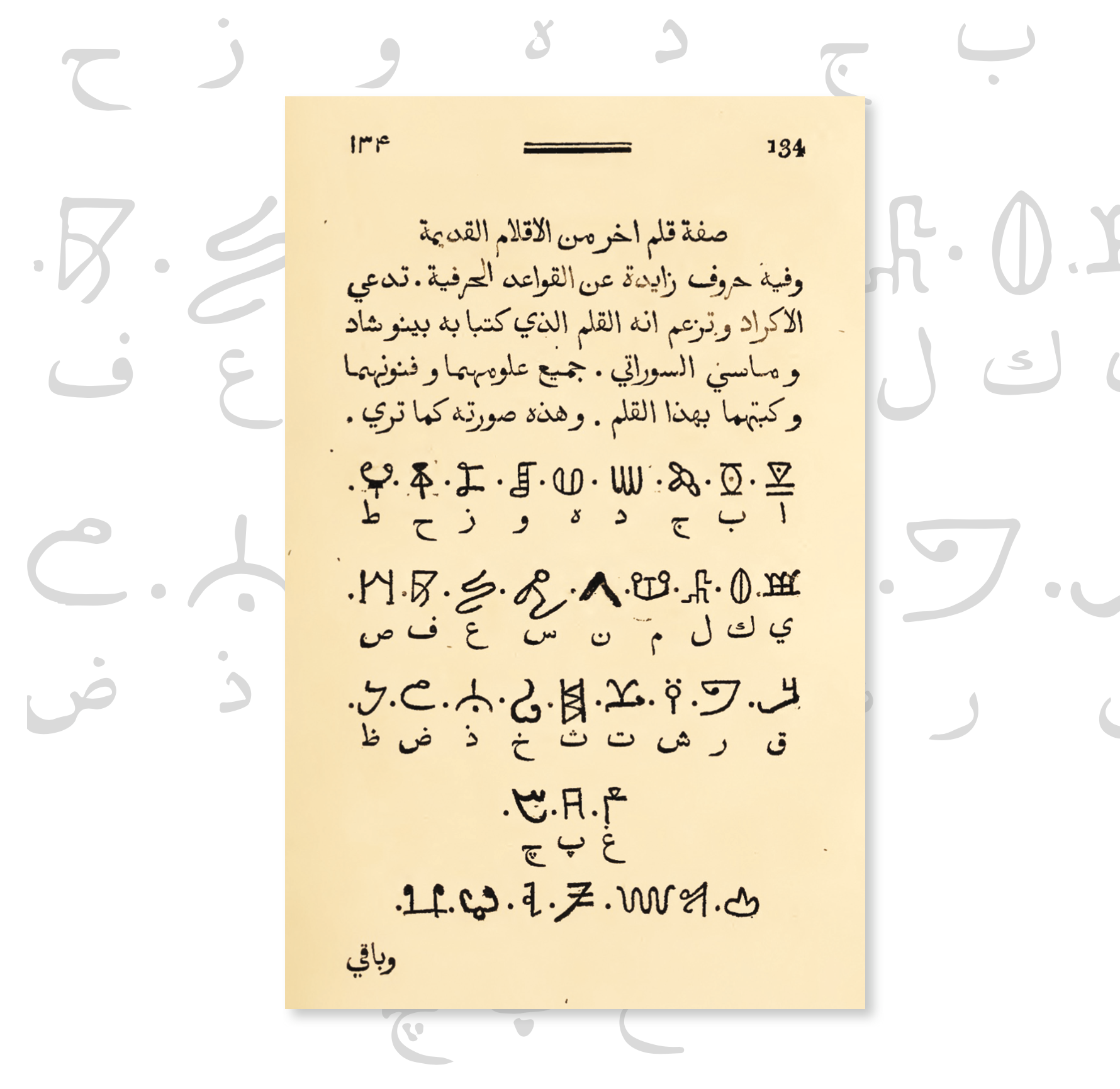

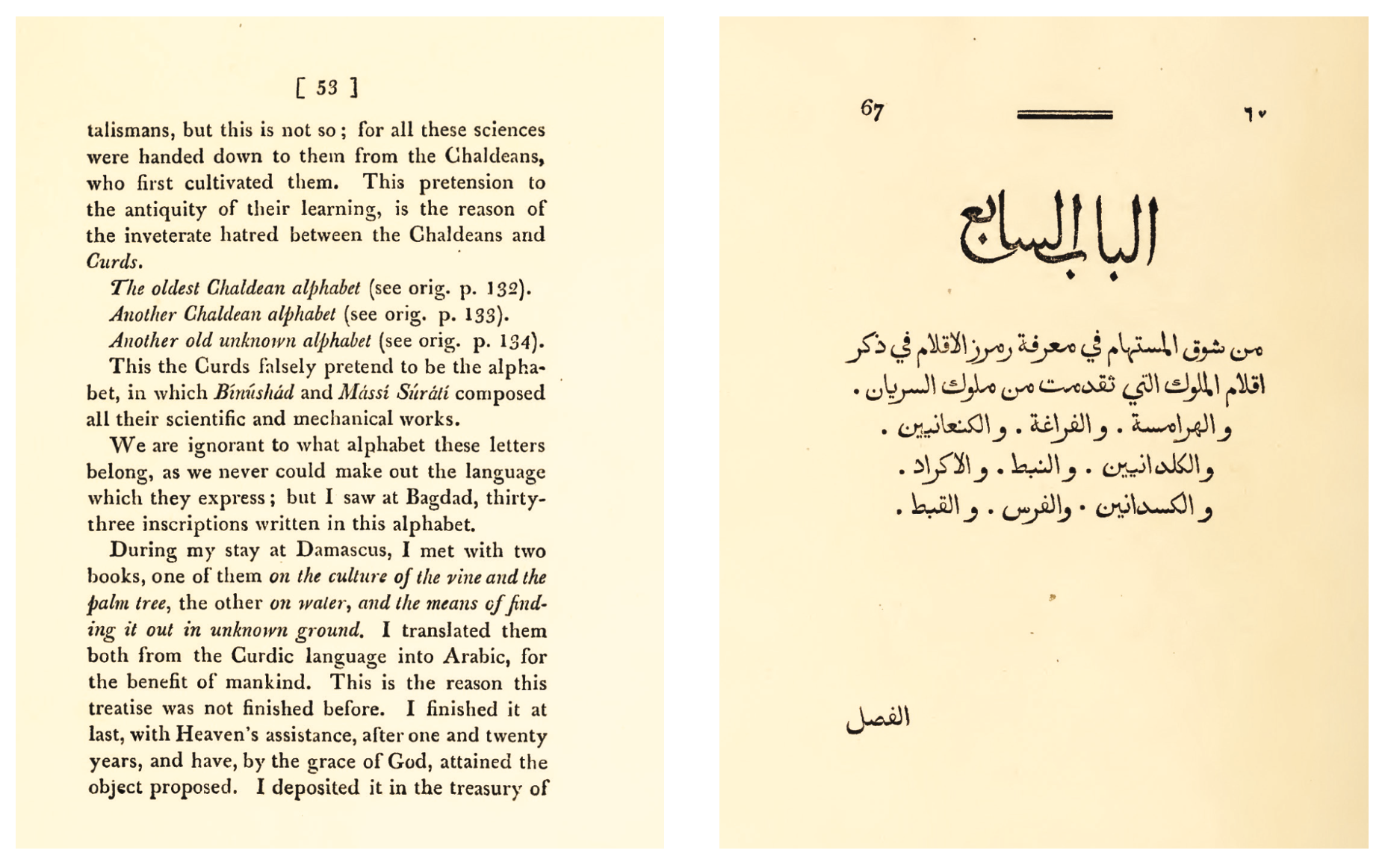

Kurds are mentioned in Wahshiyya’s work more than once, which hints at the possibility of multiple Kurdish alphabets. Significantly, the author notes a set of letters which “Kurds claim is the alphabet with which Binoshad and Masi el-Tawrati wrote all their sciences, arts, and books”. This would place the Kurds alongside other contemporary peoples of the time, who reserved different alphabets for their rarified and common people, such as the alphabet of the Assyrian kings, which differs from the Syriac letters currently in use.

History of the Kurdish Alphabet

The history of the Kurdish alphabet, according to the manuscript, dates to ancient times, as the writer divides the alphabets contained in his book into two parts: a section he describes as ancient, and another not. For example, he does not describe the hieroglyphs as ancient, although he mentions some of the letters that preceded hieroglyphs and were used by the pharaohs as an ancient alphabet. Importantly, when mentioning the alphabet of the Kurds, he includes it among the “ancient alphabets,” a description which he seems to use only to denote the alphabets of the peoples of Mesopotamia, such as the Hermesians, Nabateans, Chaldeans, and the Kurds.

Description of the first Kurdish alphabet

The Kurdish letters in his book are distinguishable from all other alphabets through things like letter count, typography, pronunciation, and translations.

Wahshiyya finds 37 letters in the Kurdish alphabet, which is the second highest number of any he studies, after the Hermesians’ alphabet. Among the collection are 7 letters for which he can find no equivalent in the Arabic alphabet.

He describes the Kurdish alphabet as one of strange letters and drawings, and the pronunciation of its letters as not corresponding to other languages.

He also fails to mention whether one should write the letters of the Kurdish alphabet continuously or separately. Nor does he discuss the direction of writing—from right to left or vice versa—although this qualification is applied to all the alphabets in the book.

Was this alphabet known and used at the time?

According to the author, the Kurdish alphabet was in use across various regions. He himself translated a number of books written in this alphabet into Arabic, which we may see as an indicator of the past importance of the Kurdish language and its spread.

What Wahshiyya’s work leaves us with then, is a surety that the Kurdish language is one of the oldest living languages still in use today. It had a special alphabet that was unique in its drawing and pronunciation, and was used to write many books of the time, some of which were translated into languages such as Arabic.

Ahmet Muaz Yakupoğlu is a dual citizen of Syria and Turkey and proficient in Kurdish, Arabic, Turkish, English, and Ottoman languages. He is currently overseeing operations at the Famer Center for Ottoman Studies in Istanbul.